BRAZILIAN MIGRANT CHILDREN AND YOUTH

THEIR LIVES AND TIES WITH THE COUNTRY

Brazilian migration to the United States has been a small flow until recent decades but increased significantly in the 1980s due to economic downturns in the country. Brazilian immigrants in the United States doubled during the 1980s, almost tripled in the 1990s, and it’s currently at its highest number at 451,000 (2017). The majority of Brazilian immigrants arrive in the United States via airplane and are able to secure an initial tourist visa. Approximately one-fifth to one-third of them are in the United States without authorization, according to Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimates. An important trend to watch is that there has been a sharp increase in the number of Brazilian immigrants who are crossing through the border, they are in the top six of the nationals apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Thus, both types of entry (tourist or border crossing) result in on Brazilians acquiring undocumented status, since after lawfully entering the United States some decide to overstay their visa date limit. To put it into context the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 which also made it much more difficult for any individual who had previously resided in the United States without authorization to re-enter through legal channels. The process of becoming undocumented influence many families’ decisions to remain the United States or to go back after six months (the maximum amount of months awarded by the US government) in the country. Once the decision is made families who were once recognized as tourists in the United States are relinquished to the shadows of not having documents.

While there is a growing Brazilian immigrant population in the United States, children, and especially Brazilian immigrant children, are rarely accounted for in both the numbers that are on the press and in the narratives of immigrant experience constructed over the years. Young immigrants to the United States, however, have one common experience – the one of attending US public schools. What that means for young children is that most of their time during weekdays will be spent in classrooms with peers and teachers in a brand new country.

Children as young as 5 years of age are discussing being undocumented in classrooms and schools around the United States. With the current anti-immigrant rhetoric that has taken over not only the United States, but also Brazilian politics, Brazilian immigrant children have given their legal status a salient position in their imaginaries. Young children’s relationship with the home country they were once in becomes inundated with immigrant talk. This talk is about documentation, lawyers, fears of deportation, reflections on what constitutes a crime, who is a criminal and the ultimate Portuguese Brazilian word to describe longing for one’s nation – saudade de casa – longing for home.

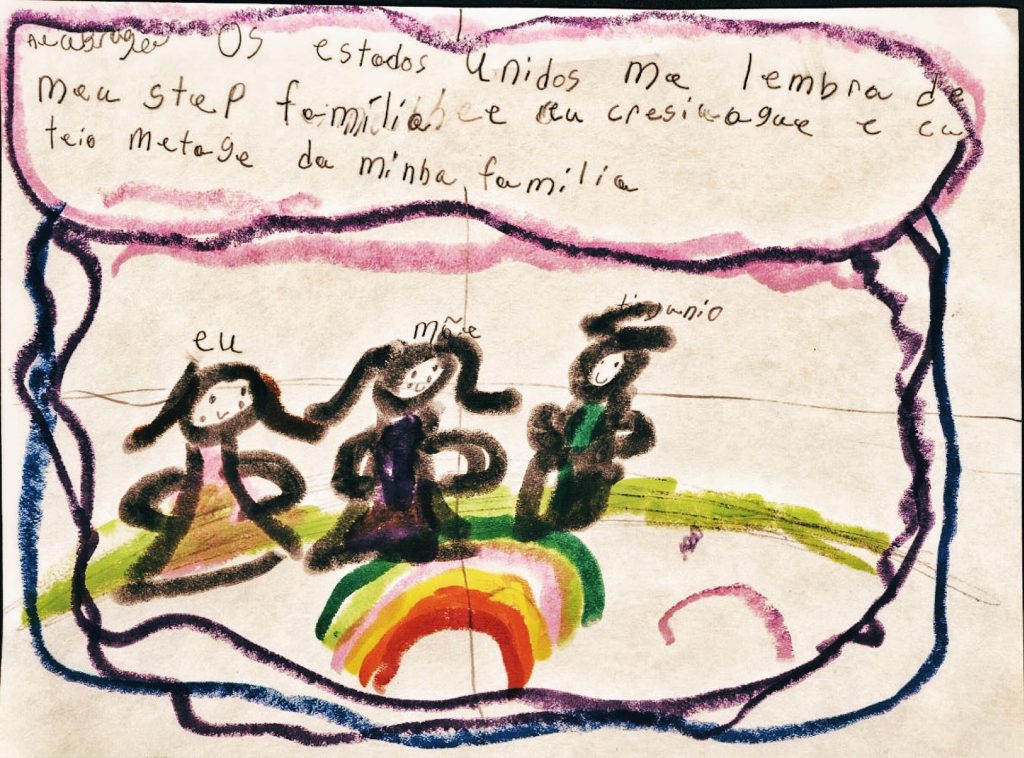

The geographical imagination of what the United States is contributes to Brazilian migration into the country. Networks of migrants and stories that detail work opportunities and success traverse physical territories and ultimately contribute to people’s mobility and movement. Children on one hand are devoid of agency as they are considered to be “brought over” to the United States, but on the other hand are agentic beings intrinsically involved in the decisions made parents and family members to move. Children are involved in the sense that the narratives from parents and family members revolve around also providing a better life for their young ones. Thus, young 5,6,7 year old children have become well versed in terms like ‘application for asylum’, ‘documents like green card’ or ‘lawyer and court’. They show through sophisticated narratives what it means to exist in the United States as an undocumented immigrant, but above all as a human being. At the same time Brazilian children maintain their transnational ties to the home country by describing the land as something that feels familiar and close and at the same time violent and unsafe. Children assemble the images of Brazil is through their parents, television, family members, contact with Brazilian friends and family, but also on their own memories of being born and having lived in the country for a few years. Children reflect on the hardships of living far away from the place where they were born. However they do that sometimes through the lens of their parents. As one child, João, 7, explained in the classroom, “Mr. Donald Trump doesn’t let my parents go to Brazil, because they don’t have the green letter (green card), but I can go because I have never been in Brazil, so he can let me go, but not parents”.

We must understand children’s role in the narratives of migration as important pieces of the puzzle, so that societies and by consequence schools can be better equipped to understand children’s stories and their needs. Public schools are, sometimes, the first interaction immigrant parents and their children have with a government agency. It is also where children spend 6-8 hours a day. Schools, thus, become a fertile ground to understand immigrant children’s experiences of living in the shadow in the United States. It is through the story of Bruna that we illustrate how children discuss immigration and belonging in their new founds homes. Bruna exemplify the work done with over 110 children of Brazilian origin. In order to understand the multitude of dimensions of global mobility, children’s narratives are usually not what most policy makes, academics and journalists may look at. In part because of researchers’ focus on what is known to be the objective truth which is not always understood as children’s narratives. Our goal here is to center the narrative on children and shift the gaze of what adults and usual credible voices have to say.

Saudade

And the Nostalgia of Belonging

Bruna is six years old. She has been in the United States for one year. Bruna is from the state of Minas Gerais in Brazil. Minas Gerais is a state in Southeastern Brazil. It is the second most populous state in Brazil and is the home of the third largest gross domestic product (GDP) in the country. Minas Gerais has a longstanding tie with the United States when it comes to migration. The flow between the locations has been in place since the early 1970s. Bruna, like many in her home state, come from a poor/working class background. She is in first grade at a public school in one state in the Northeast of the United States. This particular school has an immersion program in Portuguese which allows Bruna to use her heritage language of Portuguese during the time of instruction. Bruna is an outgoing girl. She has long black hair, round brown eyes and a broad smile. Bruna arrived in the United States via the U.S. Mexico border. Her family surrendered to an official at the border and were detained as a family for two weeks. They were released with a court date and an ankle bracelet. After three months the ankle bracelet was removed. Bruna’s parents did not show up for their court date out of fear of deportation. They are currently speaking to lawyers that could perhaps help them figure out their paperwork. Bruna’s family doesn’t have social security numbers, which is the formal registration number with the government, they do not carry a driver’s license when they drive around and Bruna worries about her family in Brazil.

Bruna has described Brazil as a place where she played in the water and had a lot of family around her. She also described the country as place of violence and no opportunities. She relies of thick descriptions of elaborate robberies and children dying in the street. She assembled those images based what she hears, sees on TV and the conversations with family members. Bruna explained that she can’t go back to Brazil because if she does she will never be able to come back to the United States. In many ways Bruna is quite right about her situation. There are several scenarios for people who overstay their visa in the United States. Most of the punishments install a ban of sometimes a decade on allowing returnees to apply for visa again. Bruna explained that her biggest nightmare is that she would be separated from her parents, because according to her she knows how separation feels. Bruna explained,

I was really young when I came here. It made me afraid when we were arrested. We came here to stay a little, but then we stayed too much. There in Brazil there was no work, my mother said…But here my mom works…I think [she work] a lot. But I can’t go to Brazil because I don’t want to separate from my mother. I don’t know if people in Brazil always come here and life is like that. My grandma in Brazil always tells us she doesn’t know why we don’t go back…she says ‘[you] living there in fear! For what?”

Bruna reads advanced books for her grade. In her classroom she longs for stories about Brazil and when teachers use Brazilian lullabies as a mode of instruction she sings them loudly and proudly. In this particular case Bruna’s main teacher is also Brazilian and due to the nature of the program, dual language Portuguese/English, the teacher thoroughly incorporates Brazilian culture into her teaching. Teachers worry about the mental health and stability of their immigrant students. One teacher explained, “It’s so hard to understand all the different dimensions of these students’ lives…they have been through so much”. Another teacher was not as empathetic, “they still have to learn English and sometimes they are lazy and don’t focus”.

In one of Bruna’s favorite lullabies the word saudade appeared. Bruna explained, “é quando você teve…ou tem alguma coisa…mas não está com você agora, mas você sempre se lembra, entendeu?” (it’s when you had…or have something…but it’s not with you now, but you always remember, understand?). Her memory and contact with Brazil are alive in her formal and informal education life. Bruna describes herself as “sem documentos” (without documents), but never uses the word immigrant to describe herself. She describes her immobility as a feature of her existence.

It’s that I am from Brazil, but now I am in America. In America I don’t have the documents, my parents say, I just have my documents from Brazil. This means I can’t leave here America, we stay here always and not in Brazil . Not where I was born, not in my house.

Here Bruna connects her legal status to her existence as a human being in what she calls “America”. She focuses on the fact that she is somewhat immobile and that this state prevents her from essentially going home. She, like other children, also engages with the formalities of nation-states that make decisions about visas, green cards and who can stay and who must go. The transitory way in which Bruna places herself may seem like not the reality of a six year old girl. However, what Bruna shows us along with other Brazilian immigrant children is that children are closer to the truth than one may thing, that children are in the middle and part of these macro movements that are heavily focused on adults.

A HEART BROKEN IN HALF

Community through their own eyes

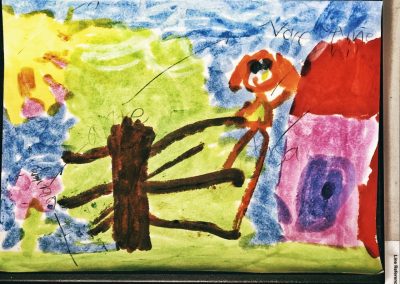

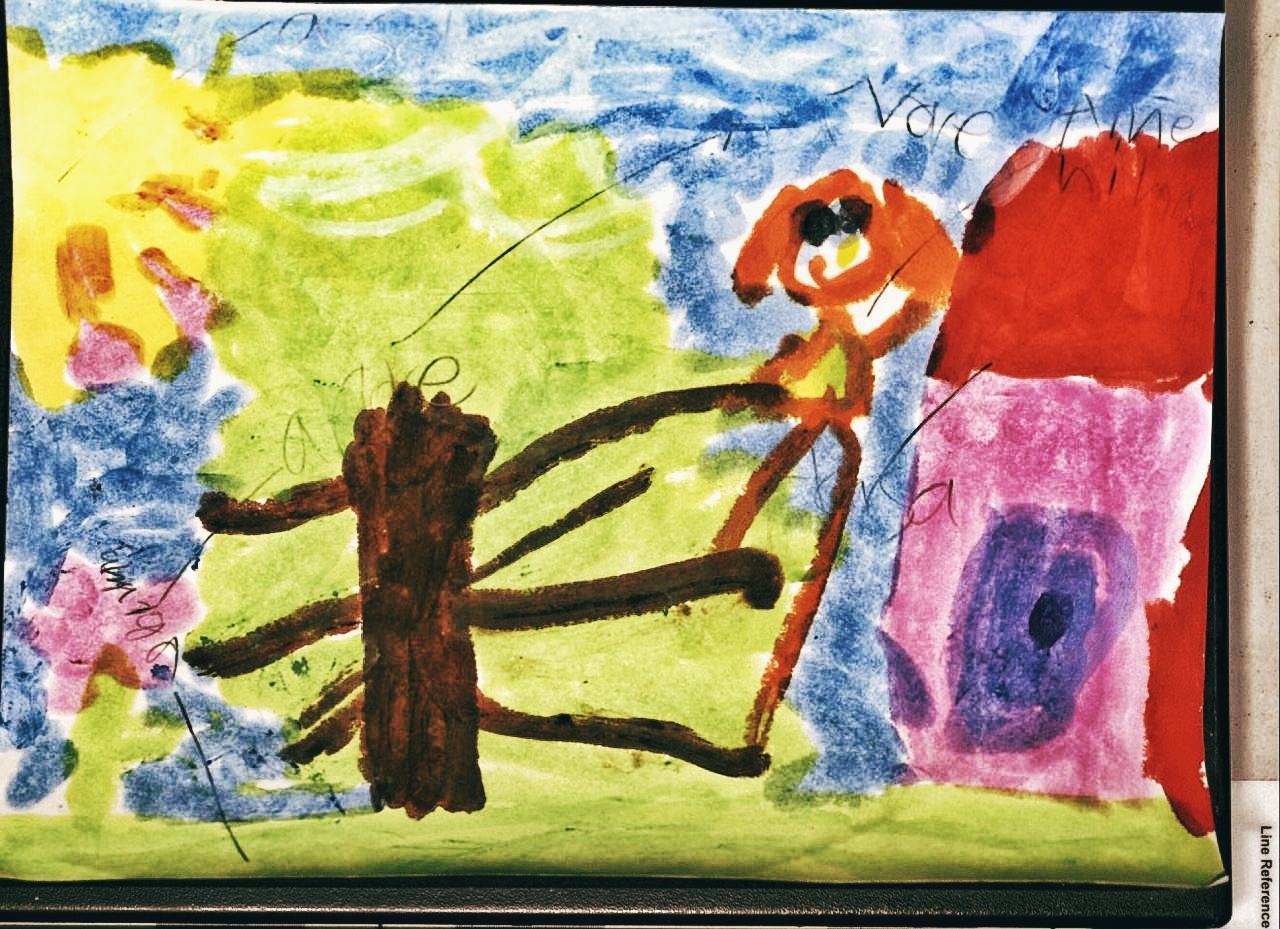

Immigrant children who are undocumented experience fear and anxiety in the places where they live. Drawings collected from this group of children show how family members and separation remain their biggest sources of anxiety. Sociologist Joanna Dreby has shown how every day, mundane aspects of existing are never without the cloud of fear that one’s legal status presents. In the communities where many children live ICE conducts large-scale immigration enforcement sweeps. In cities that are considered sanctuary jurisdictions the attempts have also been present. Bruna’s school, church and community are the main sites where belonging is asserted, contested, disrupted and desired. Her community in the United States is largely Brazilian. Bruna’s elementary school now has a language program dedicated to Portuguese. In many ways her new home in America feels like a microcosm of her own land in Brazil. She assesses the uniqueness of her community and school:

Here at least in school I speak Portuguese. Seems like there is a place in America where children from Brazil cannot even do that in school. But here I can. I can also pray in my church in Portuguese.

Bruna’s family is evangelical and they are part of a large church in one town in Massachusetts. Bruna’s daily interactions at school, home, church in the U.S. reinforce many of the ideas that exist about being an immigrant in the United States. She describes her U.S. community as both bounded and fluid. It is bounded because as Bruna puts it, “é melhor esconder na América” (it’s better to hide in America). She points out the need to remain within a specific group of people not to be visible to law enforcement mediums. However, Bruna explains that her community is fluid where she considers her town in Minas Gerais where she is from to be part of her everyday life. From a transnational perspective Bruna includes in her narratives of living her family in Brazil, her church there, her friends, her school and parks where she had gone. These assembled memories never quite leave Bruna’s nostalgic memory of belonging.

When you live in a place, but your hear is in another place. That’s what my pastor says at church. It’s ok that your heart is broken in half and that no one betrayed Brazil. It’s ok that we are here, it will pass soon.

Bruna displays her socio-emotional feelings about being divided. She also invokes citizenship and love of land by using the word to “betray” a country. As a reminder, Bruna is six years old. She discusses macro themes of belonging and citizenship in her everyday life. Even though her border crossing experience was performed by place with a tourist visa, Bruna is undocumented and no matter how far Brazil is from the U.S. physical state borders, the frontiers she encounters daily illustrate in her community reinforce her status.

Bruna

Her story and macro-processes

Some immigrant families in the United States have reportedly stopped sending their children to schools in fear of raids currently taking place across the country. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials have deemed schools as “sensitive locations”, however stories are mounting on alleged data sharing between schools and ICE. In some areas parents use different names and don’t write down an accurate phone number in fears of deportation. Brazilian immigrant parents are no different. Since the 2016 election where Donald J. Trump was elected as the 45th president of the United States anti-immigrant rhetoric has been rampant. Even though the wall may not be physically dividing Brazil and United States, the narratives have spillover effects on many immigrant populations. In many ways Bruna and her parents’ first interactions with the local government in the United States were in the school. After Bruna arrived in Massachusetts here parents went to the district education board’s office to enroll Bruna in school. Bruna went with her parents to this office for an interview. Bruna described it,

There was a huge television. And my mom and my dad wrote on a lot of papers, non stop. There was a toy for me to play with and my mom found somsone to talk with them from Brazil and not from America and then it worked. But they know we are not from here.

The idea of surveillance is not lost on parents when they are navigating a brand new school system for their children. Bruna’s dad André explained how he works in the air conditioning business. He drives around a van with equipment and does in home repairs. He describes his daily trips to and from his home and ‘holding his breath’ not to be stopped. He thinks Bruna sees and feels the anxiety: “she asks me, why are you sad, but what she means is why do I look scared, and it’s because Id on’t have documents and we see crazy things on TV everyday”.

Children, at the same time, assess some of these challenges and are able to make sense of their new found realities. Bruna pointed out to papers, translators, state, belonging and the knowledge of who is and is not from the United States. All children in the United States are entitled to equal access to a public elementary and secondary education, regardless of their or their parents’ actual or perceived national origin, citizenship, or immigration status. This includes recently arrived unaccompanied children, who are in immigration proceedings while residing in local communities with a parent, family member, or other appropriate adult sponsor. However the steps taken to register and enroll in school are official and families know that.

Bruna compared her school in the United States with her school in Brazil,

My mom explained to me that I have to obay everything here and not make trouble. In Brazil my aunt was in my school and my cousins. I knew my teacher. I like Ms. Teixeira(her teacher) but I am not to cause trouble.

Bruna was in fact incredibly compliant in school. She followed the rules, hardly complained, finished all her assignments and helped others. Sometimes her teacher didn’t have extra assignments to give her because she was that fast. Whether the school worked as a site of government control for Bruna or not she took in as a site to perform invisibility.

LEAVING BRAZIL

International migration

International Migration and Families

Migration ranks as one of the main elements that brings about global change. As a six year-old child Bruna’s narratives and experiences are constantly marginalized. Other iterations of (im)migrant adult experience become mainstream narrative. There are several reasons this is the case. First, children and their childhoods are assumed to lack agency. Children are seen by local, national and international legislation as vulnerable beings with no voice in larger socioeconomic processes such as migratory ones. According to legislation in the United States, for children of undocumented parents who are themselves undocumented obtaining immigration status may depend on their parents’ ability to obtain lawful status. The way the law is designed it marginalizes children to begin with. They are “dependent” on their parents and are described as passive witnesses of their own experiences.

Macro level processes are part of the context that motivates people to move. However these socio-economic-political frameworks don’t usually include children. In order to centralize the experience of children within larger migratory processes, stories like the one of Bruna help us understand how marginalized not only her role is, but also her narrative about her experience. Bruna’s trajectory from getting a passport in Brazil, receiving a tourist visa, embarking in on an airplane to an unknown state in the United States and enrolling in school gives us a glimpse into the constant interactions children have with formalized government agencies and agents on all levels in different nations.

Bruna, and other children in her position, understand the legal constraints present in her families’ lives. She engages with these constraints on a daily basis and she manages to be productive about it. In the school, her main governmental site of reproduction, she is seen as an outstanding student specifically because of how she manages to remain invisible when she needs to be. Remember, “don’t cause any trouble”.

Imagined Communities

For Brazilian immigrant children, the school, the community and the classroom are situated as spaces where borders are reinforced, challenged and overcome. The indignant policing of migrant bodies in everyday moments is indicative of the enduring cultural and racializing logics that restrict migrant life across the continental United States, of the ways the boundaries of the United States are intensely present in schools and classrooms at the level of the everyday. Nonetheless children actively construct ideas of what the United States is and what it represents for them. They can articulate those thoughts based on a collage of narratives developed by their parents, peers and themselves.

Bruna described her ideas about the United States before migrating:

We think that in America everything is better…that people are better, right? My mim always said that there will be more work for her, and there is more work for her. My dad works a lot too. I thought that I would have more different toys, big buildings and that we would have a nice house. I also thought about parks! But you know…no one said that it would be cold all the time (laughter).

Bruna has been in the United States for one year. She does live in a house that she shares with a number of family members. Her mother works as a cleaning lady and her father works in construction. Her refuge is her church. Bruna brings up songs she sings in church at school. She combines songs she had learned in Brazil with others she learned in the United States. They are all in Portuguese.

Jesus in the person’s heart. So even if it’s hard I pray for my grandma that is in Brazil, you know? I think about my grandma, but I know God is watching. It could be that we can go back one day to see my grandma, but the lawyers don’t know.

Bruna described her moments before arriving to the United States as opportunities for her parents and they also told her she would get a great education and learn English. This cruel optimism that took place prior to departure shapes much of the experiences her family experience in the United States. School was hard in the beginning. The hidden curriculum of knowing what to do in class, how to participate on top on knowing English were barriers not present in Bruna’s imaginary before coming. Bruna describes Brazil based on her relationships, especially with her grandmother. She wonders how long she will remember,

FORGING TIES

conclusions

Bruna and her family are actively building transnational ties with Brazil. They do that through conversations about the country, their memories and discussions of current economic and political realities. Bruna looks for outlets to speak about Brazil in her school. She does that in school in part because she is a child who is mandated to be at school for at least six hours of each day. Thus, it matters for teachers and the larger education community that immigrant children are part of school’s everyday contexts. What does it mean for Bruna to make connections between what she learns in the classroom with larger migratory experiences she has had along with her parents? It means that macro policies and migration flows impact the micro contexts where children live. The rupture of moving and changing homes is not lost in children. Quite the opposite. Children enact and narrate what it means to be an immigrant. However, their imagined communities are threatened as they exist as undocumented beings in the United States. Brazilian migration to the United States looks anatomically different from more traditional Mexican and Central American flows. While Brazilian migrants may be arriving via airplane and with valid tourist visas for six months, which signifies a level of class privilege, children in schools do not experience less discrimination because of the ways in which they have arrived in the United States.

The level of trauma and anxiety that legal status can cause on young children has been documented in recent literature. However we still don’t know enough about long term effects for children who grow up in such environment. Stories like the one of Bruna allows us a glimpse into the everyday, schooling context of immigrant children in the United States. Moving forward we urge schools and districts to think through with parents and teachers on how to better serve this population, after all to be in school and receive formal education in a human right in the United States. Several questions remain: how does the larger migratory flow impact the lives of transnational families? What kind of local and global policy can we think about to improve the lives of immigrant children? It is in these stories that we can begin to find these answers. Listening deeply to children and how they communicate. What can we learn from children?

FROM BRAZIL TO THE UNITED STATES

Million Brazilians live in the United States

Brazilians have settled in Florida

BRAZILIANS CROSSED AT "EL PASO" IN 2019

Why Is it Important?

We must document the pain migrant children feel when leaving their family, friends, and territory. Because although we may think children are very adaptable to different environments, we do not consider the trauma caused by adaptation to an entirely new atmosphere, and how this can affect their development and learning.

There is also a lack of knowledge production about Brazilian migration to the United States, despite the fact it is the primary receiving country of Brazilians abroad. It is estimated that half of these migrants are undocumented.

It is imperative to understand the psycho-social effects of migration on children given that understanding childhood development in the receiving country will help us comprehend the cultural and social changes and policies that can create more multicultural and tolerant societies.

WHAT IS THE SITUATION?

Since at least the 1960s, most Brazilians who emigrated to the United States are from the South and Central-South areas of Brazil and are middle-income and high-income. Most of them are also from European ancestry. However, there are also black Afro-Brazilians, Asians (chiefly Japanese), and people of Arab or Jewish descent.

Data from 2013 and 2014 indicate that the main metropolitan areas with Brazilian population are New York (72 635), Boston (63 930), and Miami (43 930).

According to the Associated Press (AP), around 17 000 Brazilians crossed the border at El Paso in 2019. Several of them seek asylum citing reasons like unemployment, violence, and persistent corruption.

How to Get Involved

Understanding we still do not know enough about the long-term effects of migration on children growing up in new environments. Stories like Bruna’s enable us to gaze into the daily reality and school experiences of migrant children in the United States. To make progress, we need schools and school districts to have a better understanding of how parents and teachers can best work together with this young migrant population. After all, education is a human right.