VENEZUELAN GIRLS AND BOYS

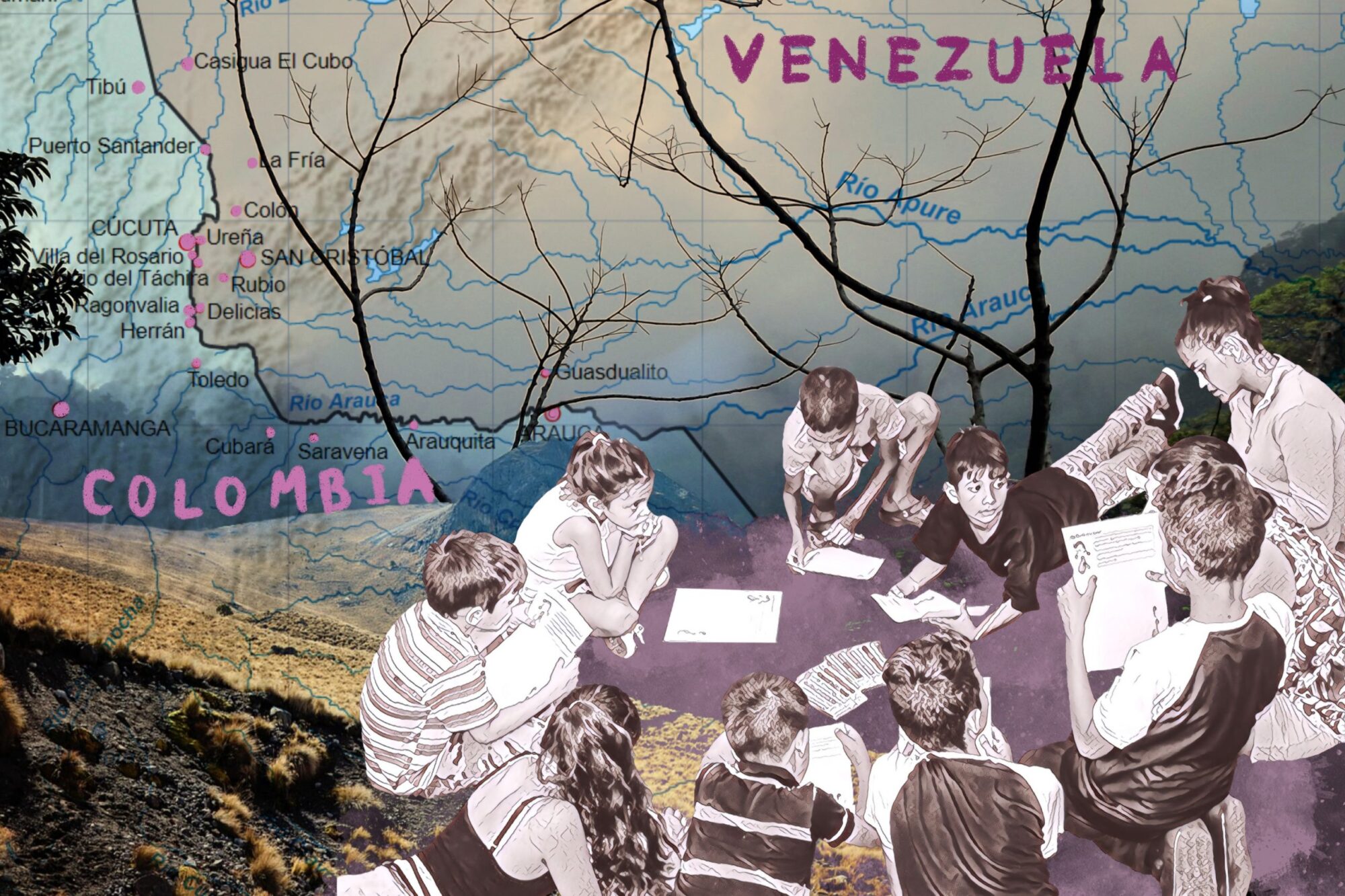

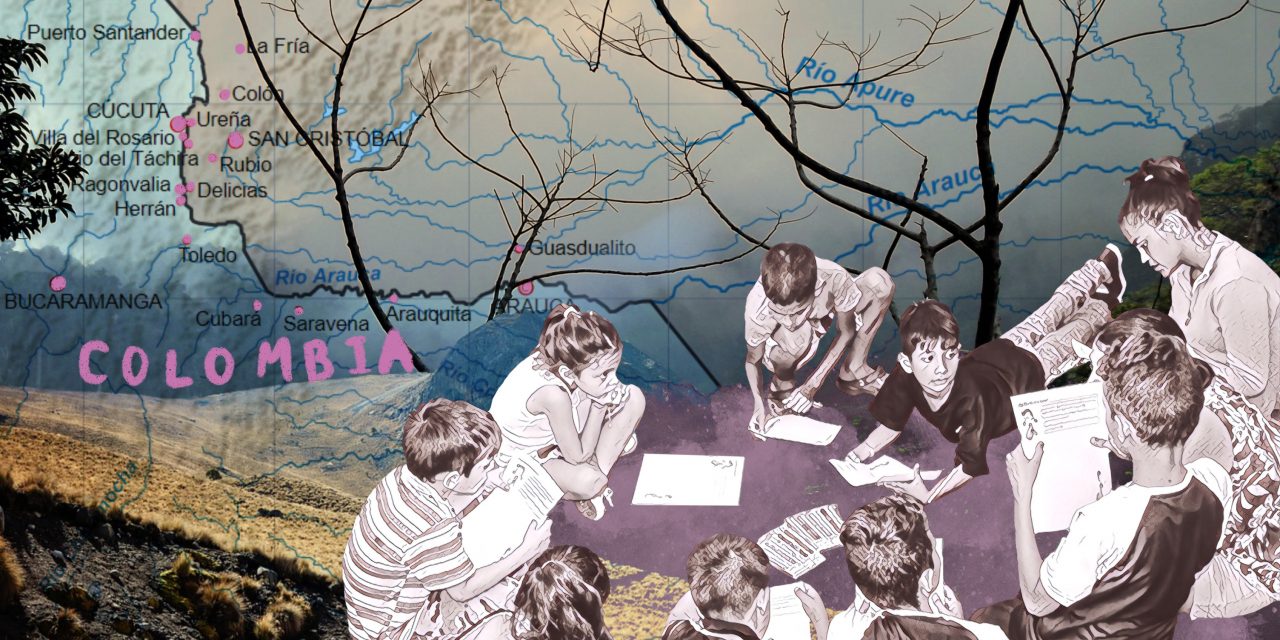

With Haversacks on their Shoulders and a Forked Road

It’s December 2018. The migrant center in the city of Cúcuta, at the border with Venezuela, is overflowing. All rooms are occupied and one can see plastic chairs in the patio. On the chairs are towels and the guests’ washed clothes. The landscape shows the presence of many people living and coexisting in this place. There are many children and youth at the entrance of the center in the outdoor corridors. Adults are also standing outside, all from Venezuela.

A Long Journey and a Quick Return

Among the different stories heard at the migration center is that of Luis, 11, a Venezuelan boy staying at the center with his mother, stepfather, and two siblings, all of them from the State of Falcón, Venezuela.

My father told us we were coming here. He was in Cúcuta two months ago and then in Bogotá. He worked and then came back, bringing us many things in three black bags and a suitcase. He didn’t come alone [the first time]. He came with other guys from Falcón. The guys he came with helped him with everything: clothes, shoes, food, medicine, and stuff like that. He brought personal use items. I was happy because he brought me many things. Before that, I didn’t have this because of the situation in Venezuela. Things were costly. A packet of cookies was a thousand sovereigns; shoes, ten thousand; a pair of pants, seven thousand sovereigns, a lot of money.

Luis says that when he found out he would come to Colombia with all his family, he searched for information about the country to learn about it. That’s how he learned something about Cartagena, Barranquilla, and Bogota, through the internet.

I learned about Cartagena on YouTube, and it’s like a coast. Barranquilla, Bogotá, I saw them, and I liked Cartagena better, and it seemed like New York. I got the Colombian map, and that appeared: the picture, the map, the places. So, when I learned that I was coming here, I wanted to know what it was like, that’s why I searched.

When I asked him about his experience on the trip, he told me that at first, he thought it would be uneventful, but then adds that he did not like it. They did so many twists and turns, and it was challenging for him because he vomited all the time. The hardest stretch was from San Cristóbal to San Antonio. It wasfull of curves that made him ill, though it took only two hours from Villas del Rosario, Colombia. They arrived in San Antonio and crossed through the “trocha” because they didn’t have a passport with them to make the official crossing through the Simón Bolívar Bridge.

The unfortunate thing of crossing by the trocha is that joke about guerrillas because when we crossed, many boys started passing gasoline and tires. And from here, from Colombia, they crossed over there, and then gunshots were heard. We kept walking. When we passed and descended a hill, we saw a long wall, and some policemen had a look at us and then sat down to have their lunch. We kept walking, and we passed another small river, we crossed, and we arrived in Cúcuta, the trip was long. They cross to Venezuela carrying tires because they don’t have them over there, and to have access to some things, you must have a “Carnet de la Patria” (native country card). Without that card, the identity card, you are nobody.

Trochas are trails or green lanes among the bushes along the Táchira river, the natural limit between Colombia and Venezuela. Those lanes were a result of smuggling activity in the region. Basic basket products from Venezuela, and gas—which is much cheaper, it becomes a profitable business in Cúcuta—have passed through the trochas. Venezuelan citizens, male and female, who don’t have a passport or the Border Mobility Card, are forced to use the trochas to reach Colombia. Thus, a market for criminal groups that control this territory has been created. What happens in trochas is well known by inhabitants on the border and authorities of both countries. Months before 2018, videos in social media circulated on how people crossing the border bridge had to drop on the ground during the hours of the day when bursts of fire were heard. The criminal dynamics has been present since before the exodus and now benefits from it.

Luis mentions that the people they paid to cross the trocha told them they could not turn to look anywhere: “We can only look ahead, walk ahead.” Logical reasoning, because in this place, crimes like murder and torture are committed. It’s better not to see.

Though his father had a border card (Border Mobility Card) that allowed him to travel officially, Luis and his siblings didn’t have a Venezuelan identity card nor a mobility permit. The father couldn’t cross by the bridge and the children by the trocha, so they decided to do it together. It’s a story shared by the families whose members don’t have a passport due to restrictions to obtain one on the Venezuelan side, namely: the high cost and never-ending formalities, as well as Colombia’s requirement of producing the document to enter its territory. Therefore, families must pay to someone to cross by the trocha.

When they arrived in Cúcuta, they had to stay in the Parque Lineal, a space in the city downtown surrounded by street people and substances users. They stayed there because the father had forgotten the way to the migrant center.

The police ordered us to stand up, and we had to do it and move. People who were there said to us: stay and lie down, if they made you stand up already, don’t pay any attention, lie down. We did that, and the police arrived again, and they made us stand up, and that happened until dawn. We asked a boy, and he brought us to the migrant center.

He now compares the experience of staying on the street with the possibility of being in the migrant center. “It’s nicer being here than outside,” he says. “At that Parque Lineal there is stealing, and they use illegal substances,” he also learned of stories of armed violence situations that happened there.

Before coming to Colombia, they lived in their grandmother’s house. However, their mother was not very happy to share the space; she wanted something for herself, her husband, and children. His relationship with his mother wasn’t very good. The uncle who also lived there had problems with authorities because of unpaid business debts. Then they went to another place, and his mother got some money and invested in buying a plot of land, but she was duped. The cash was used to get a boy out of jail. This boy threatened Luis’ mother with an armed weapon in hand, so they all had to leave.

In the migrant center, he feels better. His father must sleep in the room for men and they sleep with their mother. They share the room with another family from Maracay.

When I asked directly what they plan to do next, Luis answers they’re going to Bogotá. The other family is going to do the same. It will be a long way on foot because they haven’t managed to get resources to pay for transport.

[…] but I don’t want to go on foot. They say it’s six days walking. I don’t want to go on foot. Though they say that you’ll be fine because they give many things on the road, I don’t believe that. I also know it’s freezing in the refrigerator (as the Páramo Berlín is known) before arriving in Bucaramanga. I would love to be in Barranquilla with my brother, who is 18 and is already working there. But we’re leaving because my brother… He is with other people and doesn’t pay rent, and we can’t be there. Though he wants us to live in the same city, so we can visit each other.

Luis is always attentive of the conversations between adults and officials (of an unknown agency) as a way to try and get information that could be useful for the trip they will make. Primarily, he’s interested in getting financial resources, so they don’t have to go on foot to journey into the country. He has heard of organizations that help with transport costs. But it is December, the personnel are on Christmas holiday and will not be back to work until the last weeks of January. The possibility thus is less likely. They’ve been staying at the center for one month and the rules of the place, as well as the tiredness caused by waiting, motivates them to decide to leave with a large contingent of people that will make the trip on foot.

Luis is sad when they leave because the friends he met during this month stayed behind. He’s also sad because he will have to walk and cross through “the monster, the freezer, the Páramo de Berlín.” These names refer to the spot where low, unbearable temperatures are felt, and people traveling through it experience pain, injury, and fatigue due to the long and arduous walk. Luis says he misses his friend Víctor, who kept him company during the short time they had together in the center. Luis needs games; he’s bored because now he doesn’t have any playmates. He is aware that soon they will have to leave the center and begin the walk. For now, he hopes to be strong enough to keep going and not affect his family. He also hopes that when the situation in Venezuela improves, they can return to their country.

A year after their stay at the center, while asking adolescents that kept in contact with Luis and her mother on social media, we know they’re back in Venezuela. His mother and his stepfather had relationship problems, so he went back to Cúcuta, and his mother followed him. Luis and his brother returned to Venezuela, where they live, while his mother and stepfather settled in Cúcuta.

FROM CARACAS TO LIMA

Looking for Family Reunification in Peru

Three siblings: Ángeles, 17, Eduardo, 15, and Víctor, 9, arrived in the center accompanied by their cousin Alexander, 21- Alexander was designated as their legal guardian by their mother to bring them together for family reunification. John, a cousin of similar age, and Pedro, Ángeles’ boyfriend, were also with them. They left Venezuela for Peru to reunite with their mother. They also had to pass by the trocha to reach Cúcuta.

When their mom decided to leave Venezuela a few months before, a female friend, who had traveled that way, paid for her transportation to Peru. Her children remained alone in their Caracas’ home and got help from close neighbors, who shared their food when they could and gave them the care they needed. Networks of relatives, neighbors, and friends were of vital support to sustain themselves in their homeland, and in the places of transit and arrival.

The mother arranged all legal documents to assure that, once she found stability in Peru, she could reunite with her children. Fortunately for the family, Alexander had a passport. “I got a passport previously because my dream was to go out, travel, and know other places in the World, never to emigrate.” He got it before immigration became more complicated, and the Government began hindering the process with higher costs, longer waiting times, and even sometimes requesting U.S. dollars as payment. “It would seem the Maduro Administration is unwilling to let us go, and it won’t give it to us.” News articles mention that formalities can take up to two years, and the costs have increased; thus, although the official rate is 20 cents of a U.S. dollar, in the black-market the prices for passports range from 700 to 5500 dollars. Also, expired documents used to have an extension of two years. However, the Legislature has considered granting an extension of five years and demands authorities expedite the issuance of new documents.

Furthermore, Ángeles states that it is not only people who have the money but also those who have contacts in the government that are the only ones who can obtain the document. It’s worth mentioning that the right to migrate in search of a dream, a desire, and a future is often demanded of the countries of destination when they implement restrictive immigration policies. In the case of Venezuela, people demand the right to emigrate from their own country of origin. This demand stems from the difficulty in obtaining the document that would allow them to enter Colombia and travel to the country and to the rest of South America. This situation, combined with restrictive measures in the countries of destination, like Peru and Ecuador—which require producing a passport to enter their territory—leave hundreds of Venezuelan families in irregular status.

Meanwhile, they spend their days with other children and women in the migrant center, where Víctor and Luis have become excellent friends. They have shared games and discussions about the situation in Venezuela. During one of their joint activities, Luis asks why Víctor’s mother doesn’t come to pick them up and take them with her, and he answers:

She can’t; she must stay in Perú to work and raise money, so that she can send us some cash for the fare. I see myself on a truck, traveling towards my mother. I see myself in Lima, hugging my mother and giving her a big kiss.

Víctor bonds with other families by playing games with the children. His sister Ángeles spends more time with the women in the center, while Eduardo stays with his cousins. After ten days in the migrant center without clarity of what to do, Alexander feels an enormous weight when realizing it will be necessary for Victor to walk the long route to reach Peru. At the Center, he’s been told that the organization that provides resources for family reunification is in recess and will not resume work until January 23, 2019. His countenance reflects worry because they were not prepared to wait so long in the city. They feel desperate. Víctor repeatedly mentions that his only wish is to meet his mother, hopefully before 2018 ends, because he wants to celebrate the New Year with her. He and Ángeles have written a letter to “Baby Jesus,” in which they ask him to let them arrive in Lima soon and reunite with their mother. Eduardo is quieter, reserved. But when he talks about the situation they’re going through; he also mentions his great desire that all should reunite with their mother in Lima.

Alexander is restless and worried. He believes that the situation will force them to travel on foot, and Víctor won’t survive. But his cousin says that if that is the only way to achieve their goal of meeting their mother, he’ll try to withstand the rigors.

Two days after presenting the case before an international organization, they get transport aid for the trip from Cúcuta to Lima. They must meet the formalities required to obtain the Andean Migration Card, an official ID that allows them to pay their fare and move across the country, both in Colombia and Ecuador, and thus reach Peru. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR, coordinates the trip. The organization hopes that, when they reach the Ecuadoran border, their offices in that country will continue to coordinate the journey to Peru. Eventually, Víctor, Ángeles, and Eduardo reunite with their mother fourteen days after arriving in Cúcuta.

In Lima, Víctor voices how happy he is after eleven months of starting the journey from Venezuela and Colombia to reunite with his mom. In Lima, he attended school, but currently, he isn’t studying because they had to move from the place where they originally lived. The experience has been pleasant. He has made friends. And though some want to mock him because he’s Venezuelan, he says he doesn’t pay attention to those comments. “The Miss [teacher] and other classmates have been very good to me. They treat me with respect.”

Family reunification cases like these will likely happen more frequently, and many families won’t be able to meet all the documentation requirements, as Ángeles, Eduardo, and Miguel did. Their mother had arranged the documents before she left, when formalities were not as complicated. The situation will perhaps get grimmer because, since the end of 2018, people have informed us that there are increasingly more obstacles to getting a passport. Thus, neighboring governments and humanitarian organizations must look for solutions that allow the strengthening of family reunification processes and simultaneously ensure protection measures are implemented on these routes to avoid, among other risks, the trafficking of children.

INVISIBLE STORIES

Unaccompanied Adolescents

Among the dynamics of child and adolescent emigration, we find that adolescents are arriving in Cúcuta alone. Many of them have taken on the responsibility of leaving their country to join the workforce and send help to their families in Venezuela. These adolescents are in a very complicated situation. Their perspective is to find a job to help their families. Still, since they are unaccompanied in Colombia, they could face problems like not being admitted to shelters, where regulations do not permit children and adolescents to stay without the presence of a responsible adult caregiver. We know of these cases because the shelters report having to deny entrance to many young people in these types of situations.

In Colombia, the government entity in charge of serving this population, the Colombian Family Welfare Institute, considers them emancipated adolescents. For this reason, they don’t receive necessary care.

In a territory where organized crime agents move systematically along the border, controlling the flow of contraband, the illegal drug market, and charge for trochas or unofficial crossings, adolescents run the risk of being recruited to perform criminal activities. The Colombian government and civil society actors face enormous challenges in providing care to this specific population. The question is how to ensure protection and, at the same time, not cut short their disposition and hopes of helping their family that remained in their country. It also begs the following question: How to identify the number of adolescents that have left Venezuela and are now living homeless across the border?

Exodus and Clash

Conflicts between Colombian and Venezuelan governments exacerbate violence against migrants

The migrant center has been overwhelmed with guests since 2015 when bilateral relations between Venezuela and Colombia broke down. The murder of three Venezuelan guards at the borderline led the Nicolás Maduro Administration to order the border closure. At that time, the migrant center had to take care of all the Colombians deported by the Venezuelan government. Reports mentioned that 2 200 people were deported and about 18,000 more opted for “voluntary return”, fearful of the tension between both countries. In Táchira, the Venezuelan border state with Colombia, dwellings were marked—many built with tin and lumber, along with other sub-standard materials—where Colombian families lived. The Venezuelan government ordered the demolition of the houses. People were forced to leave the country because of the great fear produced by these actions. Colombian people and binational families who had been residing in Venezuela for a very long time were the majority of those forced to leave. In addition to the severe socioeconomic situation in Venezuela, expulsions and “returns” created a bigger problem. Many Colombians displaced by the violence in their country had crossed the border, seeking refuge in Venezuela. For these people, things became worse because they no longer felt safe in Venezuela, much less in Colombia, from where they fled.

One cause of the deportations and forced returns of Colombians has been the systematic deterioration in bilateral relations between the two countries, with the simultaneous arrival of two presidential administrations with widely divergent political views: Álvaro Uribe and Juan Manuel Santos in Colombia, and Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela. Taking into account the context of the continuation and expansion of the Colombian armed conflict into Venezuela, Colombia accused the Venezuelan government of allowing the safeguarding of guerrillas in its territory, and therefore of collaborating with them. On the Venezuelan side, the Colombian government was accused of working with the United States to bring down the government and introduce paramilitary groups in Venezuelan territory.

These tensions had concrete effects on the life of the inhabitants of both sides of the border. The closure that began in August 2015— and persists—in a border formerly considered the most dynamic in South America has deepened the economic and social crisis in adjacent cities. There has also been a more significant escalation in the long-standing criminality of the area. On the exit journey, criminals find a chance to increase their earnings by charging to allow the movement of persons across green lanes or trochas.

That's the Sound of the Border

I would love to be in Barranquilla with my brother who is 18 and is already working there.

Likewise, in Venezuela, expulsion has been caused by economic hardship, the political tension that has polarized the country, and its acute consequences for the social situation. This pressing circumstance—which the impact of limited or nonexistent access to essential foods and health care, and increased violence in some territories—generated significant mobilization of Venezuelan families that, given its magnitude and intensity, can be considered an exodus. In the beginning, it meant the departure of youths and professionals that searched beyond the Venezuelan borders for a workspace that would allow them to support themselves and send resources home to their families. Fathers or mothers left their children in the care of other adults in their homes and were forced to move to search in neighboring countries with more favorable economic conditions, waysto deal with scarcity.

As the situation became more critical, especially after the border closure of 2015, the intensity of expulsion grew, and the dynamics changed. Youths and heads of household who previously left were joined by hundreds of entire families. Specifically, a phenomenon called pendulum migration was seen more frequently at the border, a kind of movement that consists of thousands of Venezuelans, men, and women, crossing daily into Colombia to buy products that are scarce in their country, to visit relatives and/or to seek medical or education services.

According to official figures, in 2018, 468 428 Venezuelan nationals lived in Colombia with legal documents—105 766 with irregular status for exceeding their stay permit or unauthorized entry, 361 399 were in the process of legalizing their papers, and 1 600 000 persons of Venezuelan origin had received their Border Mobility Card that allows border residents to move daily between both countries, that is, through pendulum migration.

The numbers also revealed that in 2017 the composition of the movements from Venezuela consisted of 40% Colombian-Venezuelan people, 30% Venezuelan, and 30% Colombian.

During the January-May 2019 period, the migrant center served 2005 persons. Of that figure, 1385 mentioned Cúcuta as their destination city, 327 are in transit and want to travel to the interior or continue to the south of the continent, and 303 have decided to seek asylum to stay in Colombia. In Cúcuta, many of the Venezuelans there risked leaving to search for jobs outside of Venezuela and help their families with remittances from abroad.

Some families decided to leave in a group in search of a better future together, Luis and his family, for example. Others leave to try and reunite with their relatives that live out of the country, in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, or Chile, like siblings Víctor, Ángeles, and Eduardo. However, socioeconomic conditions set aside, many were forced to leave due to the political situation caused by polarization within their country. They are people that flee from violence and threats originating from political issues.

That's the Sound of the Border

The migrant center—located near the center of the city—and other shelters set up at the border, closer to the border crossing, protect, feed, give medical care, legal assistance, and essential guidance to migrants to continue the trip in Colombia or toward the Ecuadorian border. From there, they will continue their journey to neighboring countries. From Cúcuta to Bogotá, they travel on foot more than 596 kilometers of road, and those who continue towards other nations, for example, cover 857 kilometers more to reach the border with Ecuador. Venezuelan men and women walk because they don’t have enough money to buy a bus ticket—that costs around 35 dollars—to the capital city, nor a passport as an ID that would allow them to pay the fare. During this trip on foot, they must pass by the eastern range that crosses the country, experiencing different types of weather. The road starts with humid heat in Cúcuta, which reaches on average 37 degrees celsius. At two hours distance by car, they pass through the cold weather in Pamplona, around 12 degrees celcius. Then they ascend to 3200 meters over sea level, the most dangerous and challenging point for the wayfarers: the so-called Páramo de Berlín, where temperatures drop to minus five degrees Celsius. There is no official record, but rumor has it among the region’s inhabitants that three to 17 people have died of hypothermia in this section of the journey. The dense fog, rain, and cold weather become unfortunate factors and a real nightmare for those who must traverse that road.

International media have continued exposing the critical situation of hundreds of thousands of people, especially young men and women forced to abandon their families in Venezuela to look beyond their borders to obtain what they can’t get in their country. They also must flee due to the violence they experience at home and on their journey. The existence of this exodus could have been ignored, considering that for a long time hundreds of thousands of Latin American people have crossed that same border, fleeing to the north to save their lives from violence, a state of precariousness, or a combination of both, but two key factors brought attention to the Venezuelan exodus. On the one hand, the intensity of the exodus, namely, the enormous number of Venezuelan migrants that left their place of origin in such a short space of time. In 2015, data shows 697 562 people leaving, in 2017, this flow increased by up to 200%, with 1 622 109 Venezuelan leaving their country.

That's the Sound of the Border

On the other hand, there is a political reason influencing the visibility of the exodus. The Chavez administration in Venezuela is openly and directly in opposition to the United States. For this reason the drama of hundreds of thousands of Venezuelan families suffering and, for some, fleeing has provided a tool to the United States government to bring international pressure to oust the Nicolás Maduro’s Administration. The international political dispute underlying the international attention on the Venezuelan exodus is thus clearly revealed and the international interest is not necessarily for the expelled people’s experiences, but rather about how this dynamic favors geopolitical interests in the region. For this reason, figures for the number of Venezuelan migrants are a matter of dispute between the Chavez Administration and multilateral organizations, like UNHCR.

The population that has left Venezuela is very heterogeneous. At first, because of the Chávez Administration’s political decisions, families who were leaving generally had substantial financial resources. Then, professionals from the petroleum sector began to migrate. Currently, the social, economic, and political crisis of 2015 has expelled people from the middle and lower social strata. This mobilization has included women, men, and youth, mostly unmarried and, more recently, families. The places reporting emigration are as follows: Caracas, the capital district, 17%, followed by the states of Carabobo, 11.6%, and Aragua, 7.6%, and the border state of Táchira, with 11.7%.

Statistics on boys and girls arriving in Colombia are not clear. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF, approximately 327 000 Venezuelan nationals are living in Colombia. There is no mention of their migrant status, be it irregular or not. Venezuela Migration Project Observatory mentions that four out of ten Venezuelans that migrate to Colombia are children. An estimated child population of 439 529 lives in the country; 78% is less than 11 years old. According to information from GIFMN, 12% of the 400 persons who cross the Colombian-Venezuelan border every day are boys and girls.

That's the Sound of the Border

However, the National Registry of Colombia informs that, from 2015 to 2018, 25 137 children were born in Colombia to Venezuelan mothers who, due to policy conditions, have legalized documents and receive a birth certificate or record of birth, but with the proviso that it’s not valid to obtain nationality. Since families cannot return to Venezuela to do the registration formalities in their country, children are at risk of statelessness. Mechanisms like substitute mothers were used to adjust to these policy restrictions. These women helped obtain the birth certificate of the children while the parents legalized their documentation status. The Colombian Government mentioned, a year later, that it will legalize these boys and girls and grant them nationality. It’s especially worth mentioning the case of children of Venezuelan nationals that are born in other countries that are not Colombia and Venezuela. These children are provided with a birth certificate issued by those countries. If their families return to Colombia for any reason, they must stay in the country they were born in, because they don’t have valid documents in Venezuela nor in Colombia. The Colombian Government, as a receiving country, should also identify and address these cases.

As can be seen, the Venezuelan exodus has several facets, from the experiences of children and adolescents, and their families, to geopolitical conditions that cause stress in these situations. In October 2019, countries like Ecuador, Peru, and Chile began requiring that migrants present a Venezuelan passport as a control measure for entrance. Many families with irregular status were therefore held up at the Colombian-Ecuadorian border. Some families tried to seek different strategies to enter into the country. Others returned to Colombian cities to restart their lives. Several returned to Cúcuta as their final destination.

VENEZUELAN migrants in colombia

Venezuelans in Colombia

%

Are Migrant Children

%

Are less than 11 years old

Venezuelan Migration, a Recent Phenomenon

Contrary to what occurred in recent years, Venezuela is not a country with a history of migration. Colombia, in contrast, given various economic, political, and security factors, is a country that has experienced large emigration flows to Europe, the United States, and even Venezuela.

What Is the Situation?

According to Migration Colombia estimates—and because of the magnitude of the Venezuelan crisis—it is believed that at the end of 2019, the actual number of Venezuelans in Colombia could be between 1 800 000 and 3 500 000 people.

The Venezuelan exodus happened slowly. During the last decades, experts have detected three waves of migration. The first wave was made up of entrepreneurs attracted by the globalization of the economy, such as the owners of Alimentos Polar, Congrupo, and Farmatodo. Then, after Hugo Chávez came to power, there were two new waves: one of high-level executives working mainly for the PVDSA oil company, and later, high –skilled professionals and technologists.

Currently, what could be categorized as the fourth wave has taken place. According to government authorities, the return of Colombians to Colombia with their children born in Venezuela is taking place as these families seek a better future.

How to Get Involved

Solidarity is part of our human nature, despite contrary institutional discourse. Reclaim it! Do not expect a solution from Governments because that will probably never happen.

Listen carefully to the voices of these boys and girls that call us to create more just worlds. Connect with the people who are building these safe spaces called sanctuaries

notas al pie

-

En la percepción de las y los migrantes venezolanos, se adjudica a la guerrilla la presencia de actores armados en las trochas, sin embargo, se sabe que allí hay otros grupos armados de carácter ilegal, así como legales, que regulan el paso de personas y contrabando.

-

Este documento permite entradas temporales y libre movilidad por las zonas de frontera durante un plazo máximo de siete días.

-

Los niños y niñas venezolanos tienen la cédula venezolana desde los 10 años de edad.

-

Maolis Castro, “El negocio del éxodo venezolano: miles de dólares por un pasaporte”, El País, 25 de agosto de 2018, https://elpais.com/internacional/2018/08/24/america/1535121140_527084.html

-

El informe de Transparencia Internacional 2017 sobre Venezuela reporta que funcionarios públicos del Servicio Administrativo de Identificación, Migración y Extranjería, SAIME, realizan cobros, que llegan hasta los 2000 dólares, para acelerar los procesos.

-

Cifras reportadas por la Oficina de Migración Colombia.

-

Es decir, de las consecuencias que ha generado el conflicto armado colombiano más allá de sus fronteras.

-

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones, OIM, Tendencias Migratorias en las Américas, República Bolivariana de Venezuela, 2019, https://robuenosaires.iom.int/sites/default/files/Documentos%20PDFs/Tendencias-Migratorias-en-Americas-Julio-2019.pdf