dos hermanos

kevin y natalie se presentan

In this story, we will learn about the experience of a brother and a sister, Kevin and Natalie, who, during their journey in the first Caravan of 2018, were left stranded a little over two months in Hermosillo, Sonora. They traveled about 4000 kilometers across Mexican territory, from Tapachula, Chiapas, to Tijuana, Baja California. The route is thought to be a straight line from exiting a country and arriving in another but proves to be much more complex and challenging than one imagines.

We met in April 2018. They had arrived a couple of days before when the Caravan reached Hermosillo, it had to split among the different first reception centers.

The figures released by media reported that in the first Caravan in 2018, there were a little over 1200 people when leaving the southern border of Mexico. About 800 arrived in Hermosillo. No more than 500 self-identifying members of the 2018 Caravan made it to Tijuana, the last city before crossing into the United States by April and May.

Brother and sister, Kevin and Natalie, were among the boys and girls that, with their parents, were trying to reach an immigration checkpoint on the Mexico-US border. They came from San Salvador with their parents and their younger sister, Ashley.

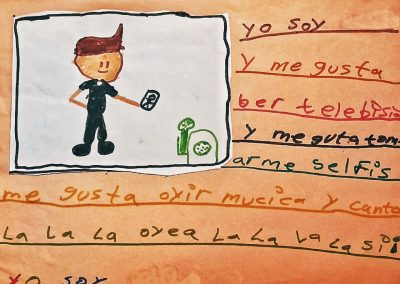

Kevin, only ten, already had a profound and clear idea of the issues his family had experienced and those to come. With a grave countenance when meeting him, little by little, he gave a big smile, more so when he started drawing and creating his television news programs or movies.

Natalie had just turned six. Through games and with her imagination, she looked for a way to get away from the harsh reality she and her family left in El Salvador and from what they experienced for some months in the Caravan. She now had a new friend, Dulce, to have fun with. Dulce also liked dancing and spinning in circles. They held hands and whirled until falling on the floor together.

In El Salvador, everything that would normally be considered simple became complicated. Going to school, shopping in the market, paying bills, everything was a challenge, even a long walk to the bus stop, because of the constant challenge of having to risk being face to face with danger when doing any of these activities, especially if one needs to take public transportation. The danger arose when “the bad guys” arrived. That was Natalie’s biggest fear. She recalled the day she couldn’t get off the bus because it was so crowded, when, with her mother and brother, they got near the school. She only managed to get off because she cried and shouted, calling for her mother.

But Natalie not only spoke about her place of origin with a sad and far away look in her eyes when she recalled terrible memories. For her, remembering the family that stayed behind was still a very intense feeling. More than anyone else, she missed her grandmother, her father’s mother.

THEIR STORY

Before the Caravan Was an Option

Carla, her mother, had little contact with her own family. Her mother and family did not like her courtship with José, the father of Carla’s children. They were 14 when they fell in love, and they were sweethearts until 17 when Carla got pregnant. Since that time, they began married life. They built their family with the support of José’s mother and brothers. The critical moment was when he went to the United States for the first time.

Kevin and Natalie were very young, and unemployment and violence forced José to cross the isthmus towards the U.S. city where his aunt lived. He had met her when he was a child. She had obtained her papers (temporary protected status, or TPS), and José was hoping she would help him. He was detained by a patrol “on The Other Side” during the first kilometers of arrival.

When they detained him, he could only speak to his family twice. The first time was a few weeks after his detention. On that occasion, he talked to Carla and reassured her that he had been well-treated, which was true. Many months later, without any information about his procedure or when he would appear before the Immigration Court, José called his house again and only found his mother. She did not tell him that his family was having one of the roughest and terrifying moments with the mara.

Days before José’s call, they had abducted Carla, supposedly because her husband had a debt with them. After three days without any food and unable to sleep, a lady she hadn’t seen before went to the mara to take Carla to the “Boss.” Face to face with her, the lady told him: “We’re not looking for her, she’s not the one. She doesn’t owe us a thing”. Carla had told them repeatedly there was no way her husband had debts with them because it had been many months since he’d gone far away.

To be a migrant is: Protect those who…. Protect people who try to cross into another country.

Carla had then another problem: she could recognize them and the lady. The men from the mara put her in the trunk of their car and drove for many hours. Carla knew that it was unlikely she’d stay alive after that night. Suddenly, the car stopped. They opened the trunk and threw her out on a street that seemed familiar. By a miracle, she was a few minutes walking distance from home. The men of the mara got back in their car and drove away at full speed, leaving Carla behind.

After a few months, one day, Carla was in her mother in law’s house where she lived with Kevin and Natalie, when someone knocked at the door. She was combing her daughter’s long hair; her mother in law opened the door, and there was José. He was fatter, his complexion whiter, his head shaved. “He was such a gringo,” said Carla, that I didn’t recognize him when I first saw him.

Seven months had passed since his detention. When he returned to El Salvador, José knew he would try to go back again, more so when he found out what happened to Carla with the mara. But before this, they needed more money. When news arrived that the family was growing, they opened a t-shirt business. Ashley was born, and two months later, Carla received a new warning from the men of the mara, this time because they learned her husband was back and had a business. They wanted money and a guarantee that they wouldn’t turn them in for the abduction.

José knew the threats wouldn’t stop. That very day, he transferred his business to his brother, packed, locked his house, and set out with his family towards the country’s northern region. He hadn’t any idea of how they were going to cross. The coyote (immigrant smuggler) who had guaranteed him two crossings would not want to assist his wife and kids. He didn’t have enough money to look for somebody else who would take all of them. Traveling without a guide was, apart from risky (because of the violence, and not knowing the way or the lack of papers), very expensive.

AN OPPORTUNITY

Meeting the caravan

In Guatemala, they learned that something was happening at the Mexican border. Hundreds of people gathered trying to cross into Mexico on “The Beast” (the cargo train immigrants usually ride to cross the Mexican territory). So, they hurried to catch the Caravan forming in Tapachula.

Listen

How was that whole month for you in the Caravan?

Elisa: How was that whole month for you in the Caravan?

Kevin: It went badly, because I slept out in the cold and the wind, and I was in danger because the bad guys were there on the street. Once I had to sleep on the road.

Elisa: So you had to sleep on the street at some point?

Kevin: Yes. In parks.

Elisa: Were you scared?

Kevin: Yes.

Elisa: But were you with your family?

Kevin: Yes.

Elisa: Did anything happened to you?

Kevin: No.

Elisa: That was good, wasn’t it?

Kevin: No, I only got cold.

Listen

[What I liked best was] going to the theater and watching a movie on a train. Elisa: How was that? You saw a movie on a train? Really?

Natalie: [What I liked best was] going to the theater and watching a movie on a train.

Elisa: How was that? You saw a movie on a train? Really?

Natalie: Yes.

Elisa: What movie did you watch? Do you remember?

Natalie: It was… It was about a… ballerina…

Elisa: How neat! What else did you do?

Natalie: We ate popcorn! Popcorn, we ate!

BEING A MIGRANT

Defending their Rights and Protecting Themselves

Listen

The experience in the Caravan was crucial for Kevin and Natalie to develop the idea of migrating. Understanding migration as a collective mobilization around a purpose, allowed them to see how hard it was to seek something that could seem so simple.

Elisa: People call you migrants. What is a migrant?

Kevin: Protect those who…. Protect people to cross into another country.

And how to stand up for those rights? What are the rights to stand up for and claim to protect oneself? In order to cross through Mexico, the National Institute for Migration granted them a 20-day transit permit. They arrived at Hermosillo on April 21, right on the deadline. The U.S. pressure was increasing, from the threats of President Donald Trump on social media to the news arriving about children separated at the border when crossing with their parents.

In Sonora’s capital, at first, Kevin, Natalie, their parents, and the rest of the Caravan got support and slept in shelters or Government facilities. At a later time, they could be seen camping on the street or improvising camps around the church.

After almost 15 waiting for “the papers” that would allow them to reach Tijuana, where they’d “surrender at the checkpoint,” the Caravan organized a protest: a 6 km walk through Hermosillo, under the 40º C sun of the Sonora desert. With comings and goings… They spent two more months there, with new protests, a hunger strike, until they finally got the transit permit papers.

Listen

What's migration?

Elisa: What’s migration?

Dulce: It’s an organization (she laughs) where you can get papers. Sometimes they’re awful because they deport you to Honduras, or your country, from wherever you come. They don’t always deport you. Sometimes they bring some papers, sometimes they do, and sometimes they don’t. Many have gotten their humanitarian visa. They gave me mine (she smiles). My mother also got hers. But many were rejected. That’s why we did the hunger strike and slept there in the immigration building.

Listen

And what does the Migrant Caravan mean?

Elisa: And what does the Migrant Caravan mean?

Dulce: It’s a group of people that… we go from one State to the next, so they’ll let us cross. It can be any border, but maybe they won’t let us pass. (silence)

Listen

What did the men who were on hunger strike do? What's a hunger strike, and why did they do it?

Elisa: What did the men who were on hunger strike do? What’s a hunger strike, and why did they do it?

Dulce: Well, a hunger strike is when you stop eating. Uh. In the morning… It’s for a while. But Irineo [Irineo Mújica, leader of Pueblo Sin Fronteras] decided to do it several days. We did it to get papers from the immigration people.

Elisa: Do you think this protest worked or didn’t work?

Dulce: The protest was OK, but because some [people] got [the papers], but not the hunger strike because they said that nobody was on hunger strike there. That was a lie. That everybody was eating.

Elisa: Is that the truth?

Dulce: It’s a lie. Because those on the hunger strike didn’t eat, even Irineo scolded us when we brought food there, close where they were, because he said he was… They threw liquids into the stomach, and it would harm them because they had empty stomachs.

After the hunger strike, the saga to get papers and decide the path and the crossing didn’t end.

Dulce

Dulce was twelve when she joined the Caravan with her mother. Before, in Honduras, she had better livelihood opportunities than Kevin and Natalie, the El Salvadoran friends she met in the Caravan. Her mother worked on luxury cruises. For this reason, she spent weeks without seeing her mother, but later on she would have “many, many days with my mother’s affection,” Dulce told me. She didn’t speak of her father, and her mother didn’t want to talk about what happened to him. The days her mother was at sea, she left a sister of hers— who had younger kids—in charge of Dulce. The girl helped her aunt by making dinner and watching out for her cousins: “We played, rather,” she recalls, when her aunt went out to work. Hence “it was better that my aunt wasn’t there.”

Less than a year before, Dulce went to a private school in San Pedro Sula, where she studied English and received her first lessons on how to cope with prejudice about her background. She said that her accent and curly hair revealed her humble background to her peers at school, even though in her neighborhood, they saw her as a rich and arrogant girl because she went to a school for well off people. She didn’t make much of this; she knew that all the sacrifices her mother made by “working hard and far away” were so that she could have a different life than what the future held for her in Honduras.

Public school in Honduras cost more than public school in El Salvador, because “don’t fool yourself… in the Honduran public school you pay, and it’s dear.” By this statement, she was referring to the maintenance payments parents were forced to pay in Honduras starting a few years back, and that now contributed to the government’s strategy of transferring the financial issues the country is facing back to the people.

The last time her mother went away for work for two weeks, she promised Aída it would be the last time she would travel alone. The next time, they would go together “to the other side.” With a hopeful smile and a little anxiety, Dulce recalled that during those weeks, when her mother was away, she began to select what she would bring with her. This included some of the clothes she liked most and a set of small porcelain cups with which she used to play with her cousins.

In this way, Dulce and her mother joined the Caravan. During the journey, her friendship with Natalie and Kevin made the hard days through Mexican territory more colorful and fun.

After exhausting days in the cold, under the sun, some interviews with the media, and many negotiations with government authorities, Dulce thinks back to the good things that happened in the Caravan. And, of course, the joy of finally getting “the papers.”

THE GREAT WOUND

Meeting the Big “Wound of Inequality”

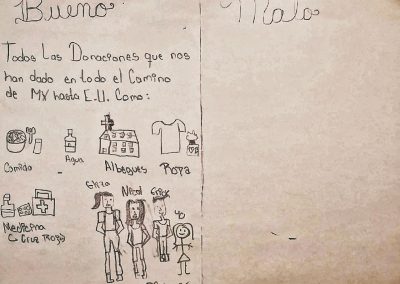

The journey was not only 4000 kilometers long. It was cold weather, boarding and coming off the train, infections, hopes, hunger, donations, days without a bath, fears, dreams, interviews with reporters, dehydration, temporary permits, days with a bath, lost backpacks, hot weather, games, tedium, protests, friends, phone calls, rains and much more. All to face on your own before reaching the wall at the end.

For Kevin, Natalie, and their family, hope and anguish made them weary in making a decision: Pass through Tijuana? Most members of the Caravan made that decision. Attempt the crossing through Mexicali or Nogales, where perhaps there would be fewer people? If these were their only qualms. The days before the Caravan was preparing to leave Hermosillo and head to Tijuana, Kevin and Natalie’s family received the support they needed to stay and not continue the journey. They could rent a small house, and José began to work cleaning a department store in a big mall. Kevin and Natalie were super happy because they didn’t have to sleep on the floor, because there was a T.V., and they could play with the puppies of the main house.

Doubts about staying or moving on are always present during the journey for people seeking refuge in the United States. Since 2017, at the start of the Trump Administration, fear and mistrust, ever-present in their path, were now more tangible.

THE WALLS

On the Other Side

On January 25, 2017, five days after taking up the office of President of the United States, Donald Trump signed Executive Order 13767. This document sets out, if not all, a large part of the courses of action he boasted loudly throughout his campaign. Among these promises was his goal of building a significant extension of the wall on the southern border of the United States. Besides determining the allocation of resources to reinforce security and the Border Patrol (hiring more than 5000 agents), he requested the development of new political guidance by the DHS (Department of Homeland Security) to end what he called the “catch and release” policy.

Just like this, the main tools for implementingthe “zero-tolerance policy” of the Trump Administration began to take shape. The grand strategy consisted of realizing that no legislative change was necessary to use harsh procedures and mechanisms like separating children from their families.

With the understanding that all crossings by undocumented migrants must be considered a crime, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has prosecuted, since the beginning of the Trump Administration, all persons identified at the border as not having a defined legal migrant status at the border. Among these are asylum seekers and adults accompanied by children.

The DOJ used to only identify severe cases: those considered as a threat to national security; people who had a criminal conviction in their country of origin; suspected of involvement in trafficking in persons, mainly children, or people who had previously attempted to enter the United States without documents.

Considering the Flores Accord, the new executive guidance took advantage of the prohibition of detaining children in the same federal facilities where migrants over 18 are detained. This way, when holding every person who tried to cross, separating children from their parents became the cruelest rule applied when they arrived in the United States. They are separated to be later considered as unaccompanied minors. Then the authorities argue the children need protection from the State because their parents or guardians are being criminally prosecuted.

The Caravan is a group of people that… we go from one state to the next so they’ll let us cross. It can be any border, but maybe they won’t let us cross.

The separations occurred during previous administrations, but the goal then was to identify, with reservations, those persons who could seek asylum or other permits and protections available by law. Also, presumably, the first alternative was to release asylum seekers, even if people had to wear electronic ankle bracelets. In deportation cases, the objective was ensuring family unity.

On April 26, 2018, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued an official statement to the Senate, which claimed it was unable to determine the whereabouts of 1475 children awaiting regularization in the country and were under the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). The agency claimed that between October and December of 2017, there were 7635 children with sponsor families, 6075 were still with their sponsors, 28 had run away, five deported, and 52 living with someone else.

These facts reveal a series of important issues. The first issue relates to the ability of U.S. government institutions to evaluate the exposure to risks of migrant children and their vulnerability when being released to sponsor families. The second issue is the great difficulty for these children’s families to decipher the complex and inaccessible U.S. immigration system, which often makes it impossible to understand whom to notify changes in personal contact information. Finally, in a “zero tolerance” scenario, the persons responsible for these children are their parents who are seeking to regularize their immigration status. They are fleeing from all possible forms of contact with government authorities, including, for example, not sending their children to school or hospitals.

Something to take into account is that the measures taken by the U.S. government are accompanied by a national security discourse on crimes potentially committed by migrants, mainly violent crimes against U.S. citizens with links to drug trafficking. Next to this discourse, in the U.S., there is a big migrant incarceration industry based on private sector organizations responsible for the construction and maintenance of facilities and monitoring devices for the border.

THE FOLLOW THEIR PATH

Natalie, Kevin, and their Family

In this context, Kevin’s family was speding n the whole day with the T.V. turned on. While Kevin was happy because he was close to realizing his wish of a different life from the one his dad had lived in his country or Mexico, he also knew that as he got closer to his goal, responsibility and tension grew much more. His father explained how important Kevin was in case something happened to him: Kevin would have to take care of his mother and sisters because his father had been previously detained, and this could happen again.

What for many would seem enough reasons to give up, this didn’t have that effect on José and Carla. The lack of prospects and everything they had faced to reach the place where they were, transformed the meaning of resignation. For them, to stop trying was not an option. Patience, adaptation, and insistence are keys to making decisions and move forward.

If their fear in fact happens and U.S. authorities forcefully separate them, they would move on and continue themselves. At first, José thought of crossing alone because he was detained seven months when he tried crossing a year before, but now he would do it with Kevin and Natalie. If they were separated, Kevin, ten, would be solely responsible for his sister Natalie, six. Carla would cross with As

In this context, Kevin’s family was speding n the whole day with the T.V. turned on. While Kevin was happy because he was close to realizing his wish of a different life from the one his dad had lived in his country or Mexico, he also knew that as he got closer to his goal, responsibility and tension grew much more. His father explained how important Kevin was in case something happened to him: Kevin would have to take care of his mother and sisters because his father had been previously detained, and this could happen again.

What for many would seem enough reasons to give up, this didn’t have that effect on José and Carla. The lack of prospects and everything they had faced to reach the place where they were, transformed the meaning of resignation. For them, to stop trying was not an option. Patience, adaptation, and insistence are keys to making decisions and move forward.

If their fear in fact happens and U.S. authorities forcefully separate them, they would move on and continue themselves. At first, José thought of crossing alone because he was detained seven months when he tried crossing a year before, but now he would do it with Kevin and Natalie. If they were separated, Kevin, ten, would be solely responsible for his sister Natalie, six. Carla would cross with Ashley, who wasn’t quite nine months, and thus they wouldn’t be separated, he thought.

Carla, who stayed with Ashley for five days, spoke about how hard and cold were the days they spent there. Ashley had a sore throat again, but they confiscated the medicine they had, including the antibiotics she was taking. They sent both of them to cages, where there were only women and small children. Carla recounted that the more the children cried, the more they felt the air-conditioned being lowered. For food, always the same sandwich, all day long. Carla felt very depressed and knew Kevin and Natalie were feeling the same.

But at the moment, that was less important. The family was together again. They managed to rent the attic in a city house where they awaited their appearance before the immigration court. José and Carla wore electronic bracelets while looking for jobs and a school for the children. Little Ashley had learned to walk. Natalie wore her hair longer than ever before. Kevin got a notebook and a small pencil and resumed his drawing.

When Kevin and Natalie’s family migrated as a whole family and opted for collective action through the Caravan, it showed a different logic to migrating. However, it’s still apparent how dependence on a State concession defines what it means to be a migrant child:

Elisa: What does it mean to be a boy, or in your case a girl, who migrates?

Dulce: (silence) Well, they… In this case, we can’t do anything.

Elisa: Why?

Dulce: Because that’s… It depends on them [the INM]. Let’s say, if they want to grant you a visa, they give you one, and if they don’t, they don’t grant it, they deny it.

Elisa: When they say that you are a migrant girl, what does it mean?

Dulce: (silence) Well, migrant girl means simply migrating all the way here from your country.

Elisa: In other words, leave one’s country.

Dulce: Yes, only that.

Elisa: ¿Did you like migrating?

Dulce: Yes, it was a lot of fun.

The process of migrating to the United States doesn’t mean a boy or a girl matures faster. But to be seen as children or not, being recognized as children during the journey, directly alters their possibilities along the route. Because of this, the restriction of their rights—of communication, of maintaining bonds, of adequate access to information concerning their rights, etc.—dressed-up as “the child’s higher interest,” or something similar, is a strategy of a punitive State, with policies geared exclusively towards a national security discourse. These policies, in turn, are implemented by institutions that see the return and immediate deportation as the solution to their bureaucratic problems, or worse still, the great business of mass incarceration.

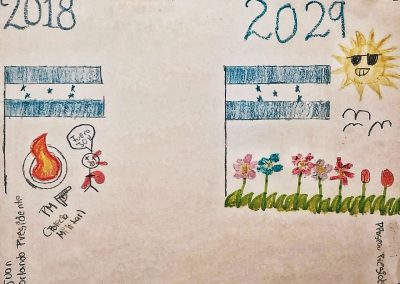

In this broad “gray zone” of immigration, an organized Caravan through the “Country without Borders” intends to bring an alternative to clandestine and undocumented immigration, making visibility its primary strategy. Countless stories of suffering could be shared about the children in the Caravan. Kevin and Natalie’s story, brother and sister, and of their parents is an example of what these stories mean. In this case, they realized that life in El Salvador had become unfeasible after several events: the unsuccessful attempt of their father of finding a job in the United States, the kidnapping of their mother, and later threats by gangs. Joining the Caravan was an big opportunity to seek asylum in the United States and to be closer to a safe life. A life they didn’t find during the few months of their journey through Mexico.

BY THE NUMBERS: POLITICAL ASYLUM

Interviews in 2018

%

Were Granted Asylum

%

Were Granted the Right to Stay and Work

Why Is it Important?

Mobility dynamics around the world put into perspective structural inequalities. To some, these inequalities present themselves as opportunities to improve their situation. For many others, it presents itself as a risk and a form of survival. Central American migrants that travel across Mexico toward the United States reveal that when they leave their countries—due to poverty, death threats, or lack of opportunities—their journeys are branded with precariousness and vulnerability.

However, by moving in response to these challenges, they tranform into a new political actor, further transformed as each individual joins the Caravan. The inequalities that push people to move are then prioritized in the public agenda and, through the solidarity and resilience of Caravan participants, the members of the Caravan are able to build other ways to escape from this obscurity, invisibility and secrecy.

For the children, this Caravan experience allowed them to understand themselves as a subject that can asserts their rights: to migrate, to seek asylum, or simply to have shelter and food, without being vulnerable to extortion or to being separated from their families.

What Is the Situation?

Only around 20% of asylum seekers are granted the right to live and work in the United States. Of the 100 000 interviews held in 2018, almost 75% were approved. However, due to the restrictions imposed by the Trump Administration, there has been a sharp decline in that percentage.

Unaccompanied minors that have been victims to violence and/or crime or have been trafficked and wish to seek asylum in the United States can do it under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act. This immigration relief can be received via a T visa (for victims of human trafficking) and U visa (for victims of criminal acts). According to Syracuse University, 86,470 cases of unaccompanied minors—mainly from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala—were filed. This number is based on the date from which data was requested from the federal government under the Freedom of Information Act between October 1, 2013, and December 31, 2015.

In 2017, a total of 8759 cases of human trafficking affecting more than 10 000 victims were reported to the National Human Trafficking Hotline (NHTH).

How to Get Involved

Mexico has become a place of destination, long-term permanence, and also a refuge for thousands of Central American children and adolescents, and children and adolescents from other countries. The government and civil society must protect their right to migrate, to receive humanitarian help, and international protection. Your support is essential to sustain the vast network of shelters that aid and protect these children.

References

Congressional Research Service, CRS, The Trump Administration’s “Zero Tolerance” Immigration Enforcement Policy, CRS, Reporte R45266, 2018, https://crsreports.congress.gov

Terrio, S. J., Whose Child Am I?: Unaccompanied, Undocumented Children in U.S. Immigration Custody, California, University of California Press, 2015.

The White House, Executive Order 13767: Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements Federal Register, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-border-security-immigration-enforcement-improvements

“Trump Speech to the Nation: Fact Checks and Background”, The New York Times, 9 de enero de 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/08/us/politics/trump-speech.html

U.S. Department of Justice, Attorney General Sessions Delivers Remarks Discussing the Immigration Enforcement Actions of the Trump Administration | OPA | Department of Justice. San Diego, DOJ, 2018, https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-sessions-delivers-remarks-discussing-immigration-enforcement-actions