BINATIONAL STUDENTS

A Snapshot of Alondra’s Life

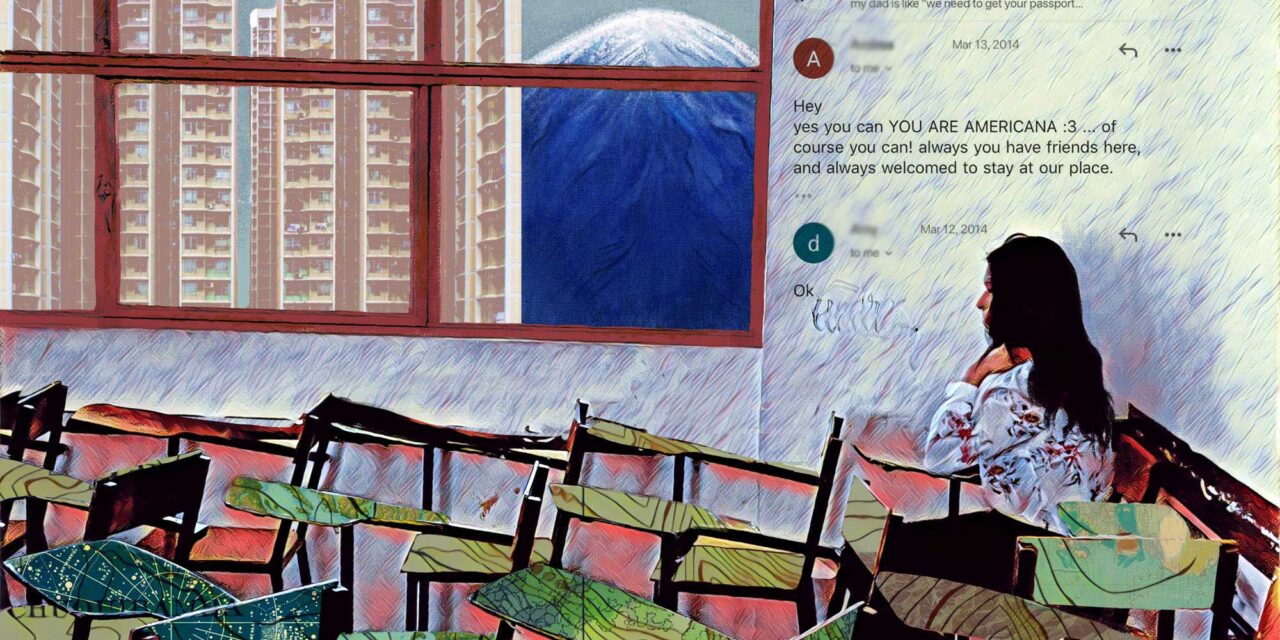

It was a Friday morning during a math lesson about currency conversion when Alondra’s mother appeared in the doorway of her high school classroom in Puebla, Mexico. One classmate commented that his suegra, or mother-in-law, had come to visit, which elicited ‘ooohs’ from the rest of the students due to the untrue suggestion that he and Alondra were romantically involved.

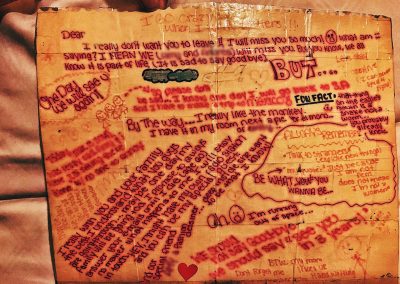

In the far back corner of the room Alondra sat with her eyes down, with one ear bud playing Rhianna, Bruno Mars, and her other favorite artists, her notebook filled with ornate sketches of hummingbirds and her dream quinceañera dress rather than the teachers’ dictations she was supposed to be writing down. These were strategies she used to distance herself from her classmates and schooling in Mexico, where she often felt she did not belong. She kept her eyes low as she crossed the room and stepped outside in the morning sun, the snow-capped volcano filling the skyline behind the four standalone classrooms that comprised her 100-student high school. This was not how she had imagined her senior year of high school when growing up in New Jersey.

The Invisibility of North-South Migration

Alondra, a high school senior, is like more than half a million US-born children who now go to school in Mexico. Although migration is often assumed to move from Mexico to the US, over the past decade this has changed with more Mexicans returning to Mexico than going to the US. Deportations are one of the reasons families return to Mexico, as they are at their highest historical rates under the Obama and Trump administrations. But there are other reasons families return, like reuniting with their loved ones. Many families are mixed-status like Alondra’s— she and her sister were born in the US and so they are US Citizens, but her parents who arrived from Mexico as undocumented teenagers did not have official US papers. This meant that if her family went to Mexico for any reason it would be difficult for her parents to re-cross the border.

Why Families Return

Discovering binationality

Learning to be Legal…

Born and raised in New Jersey, when Alondra was 15 her parents decided to move back to Mexico- a country she had never even visited—to help care for her grandparents. This move meant leaving behind childhood pets, lifelong friends, and the only way of life she had known. She moved from a bustling urban center near New York City to an 8,000 person town at the foot of a volcano. Like many who return, her family had to start with nothing and occasional material pleasures—such as new clothes or eating fast food—were no longer within their financial means. Once in Mexico Alondra faced challenges when she started school. The first was navigating the bureaucratic process of enrolling in school, which took months. Once she began school she also faced major academic challenges. In New Jersey she had attended English-medium schools and although she could speak Spanish with her family, she had never had the opportunity to learn academic Spanish or literacy. In her school, and in most parts of Mexico, there were no special classes to develop “Spanish as a Second Language,” or the equivalent of “English as a Second Language” (ESL). As someone who had not grown up in the same place as her classmates, they saw her as different and she faced bullying. Although it was hard, Alondra graduated and wanted to go to college. She tried several avenues to work and save money to go to college in Mexico, but the extremely low wages and limited scholarship or loan programs left her with few options. So, when she was 19, she moved back to New York City to work and save up for college, leaving her family behind.

These experiences highlight an overlooked aspect of how immigration policies shape children’s education. Although more kids like Alondra are enrolling in Mexican schools than ever before, few structures or policies exist to support these binational students or the teachers. Alondra’s trajectory shows the importance of working toward policies between Mexico and the US about schooling for the young people who so gracefully navigate life and learning on both sides of the border. In today’s political climate this is more important than ever.

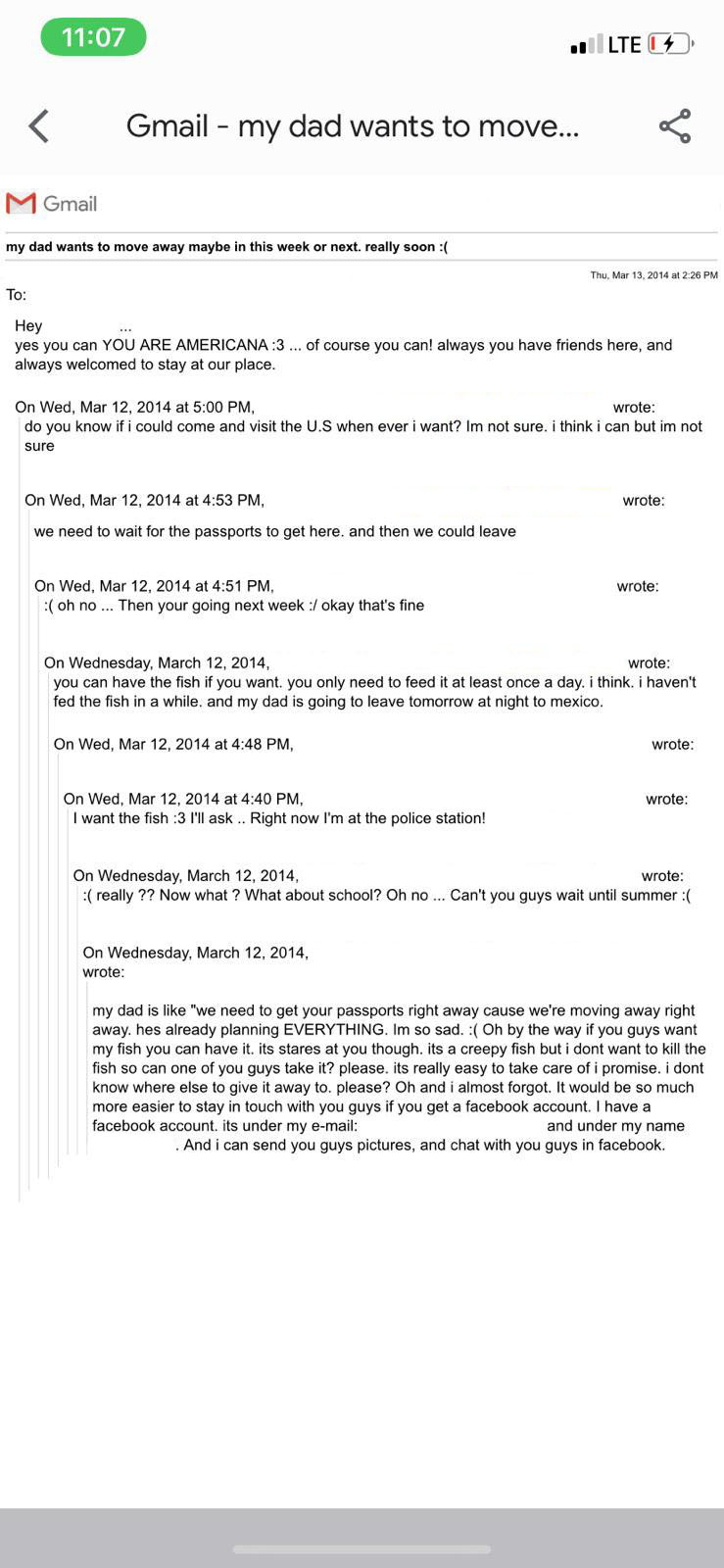

She emailed her two best friends the day her father announced their return to Mexico, navigating her social world as a teenager against a backdrop of looming immigration policies. Children like Alondra are binational— they are US Citizens because they were born in the US and also Mexican Citizens as anyone with at least one Mexican parent can apply for Mexican Citizenship. Yet her family’s move to Mexico pushed her to begin to tangibly understand her binationality, and how it differed from those in her family who were not born in the US.

Before moving to Mexico Alondra waited for her US passport to arrive, but initially was not sure what that meant about her future travel to the US. She asked her friend “do you know if i could come and visit the U.S. when ever i want? Im not sure. i think i can but im not sure.” As someone who had always lived in the US, she had never had to consider before if and how she could leave or return, and she turned to those she trusted, her best friends, to try and understand what leaving the only country she had ever known might mean. Her best friend assured her “yes you can (return to the US) YOU ARE AMERICANA.” In contrast to 1.5 generation immigrants who moved to the US without authorization as children who are often described as ‘learning to be illegal’ in late adolescence as they concretely come to understand their undocumentedness when they are unable to cross major milestones such as getting a driver’s license or first job due to their lack of US papers, here Alondra’s family’s move to Mexico created a context in which she began to learn about her legality, or the privileges of having US papers. These privileges, of course, were not universal across her family members.

LEAVING A LIFE BEHIND

From North to South Challenges of School Access

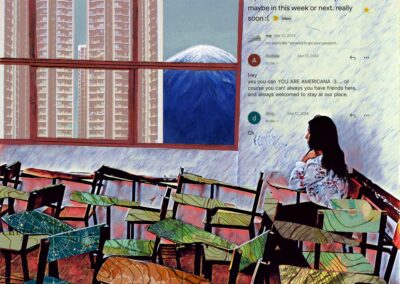

She also faced practical realities of a sudden move across borders, such as convincing her friend to care for her pet fish. In the same email announcing her family’s departure she asked her friend— “Oh by the way if you guys want my fish you can have it. Its stares at you though. its a creepy fish but I don’t want to kill the fish so can one of you guys take it? Please. its really easy to take care of I promise.” This move entailed major life changes for Alondra—leaving behind childhood pets and lifelong friends she could turn to for help. Alondra remembered, “I wanted to stay in New Jersey because I had my friends there and it was difficult to move to a whole new place, living there my entire life.” Four years later she still held on to the laminated poster her two best friends had made for her, written in neat handwriting in pink markers, filled with promises of always staying in touch and stick figure drawings of the three best friends together.

Moving North to South

The move to Mexico was not easy. She moved from a bustling urban center near New York City to an 8,000 person town at the foot of a volcano in Mexico. They moved into a simple home owned by her mother’s family, in which various rooms were arranged in their own stand-alone buildings around a large open yard where they raised turkeys, ducks and other small animals. Most of the food they now ate was prepared by her mother over a wood-burning outside oven.

Comparing this to the home they rented in New Jersey, Alondra noted, “I liked it there [in New Jersey] because most of the time that I was home I would be inside the house. And here most of the time I’m outside.” Like many families who return to Mexico from the United States, their economic situation changed dramatically. As Alondra’s father emphasized, what you could earn in 1 hour in the US was equivalent to a day’s work in the fields in Mexico—the main local economy. Her family had to re-start with nothing, and the occasional material pleasures—such as new clothes or a family outing to a fast-food restaurant—were no longer within their financial means within Mexico. As Alondra’s mom often joked—she did not miss the stress and never-ending work hours in the US, but she did miss the cheque, or paycheck, that afforded them a much more stable life economically.

The Challenges of School Access

Once in Mexico, Alondra faced several major challenges as she transitioned into Mexican schooling. The first was navigating the bureaucratic process of enrolling in school. As the child of Mexican nationals, she was guaranteed the right to schooling, but she also had to have her previous schooling records from the United States translated into Spanish and accepted before she could enroll, which took several months. The next obstacle was the cost of high school. Although on paper high school has been required in Mexico since 2012, in practice it is often inaccessible and requires costs such as inscription fees, books, and uniforms. Alondra and her family made substantial sacrifices so that she could continue her studies.

Once she began high school she also faced major academic challenges. In New Jersey she had attended English-medium schools and although she could converse with her family in Spanish, she had never had the opportunity to develop academic Spanish or literacy. In her school, and in most parts of Mexico, there are no special classes to develop “Spanish as a Second Language,” or the equivalent of “English as a Second Language” (ESL) that are mandated for students developing their academic English in US schools. Alondra talked about teaching herself how to read and write in Spanish for school, and still—3 years after she returned— she was unsure of how to say or write many things in her classes. Alondra’s teachers were largely puzzled by her shyness and behavior and felt that Alondra was not trying hard enough in school, as they had not been trained in working with multilingual students and didn’t understand the many challenges she was facing.

¿Cómo estás alondra?

Intimidada por ser diferente… ?

Bullied for Being Different

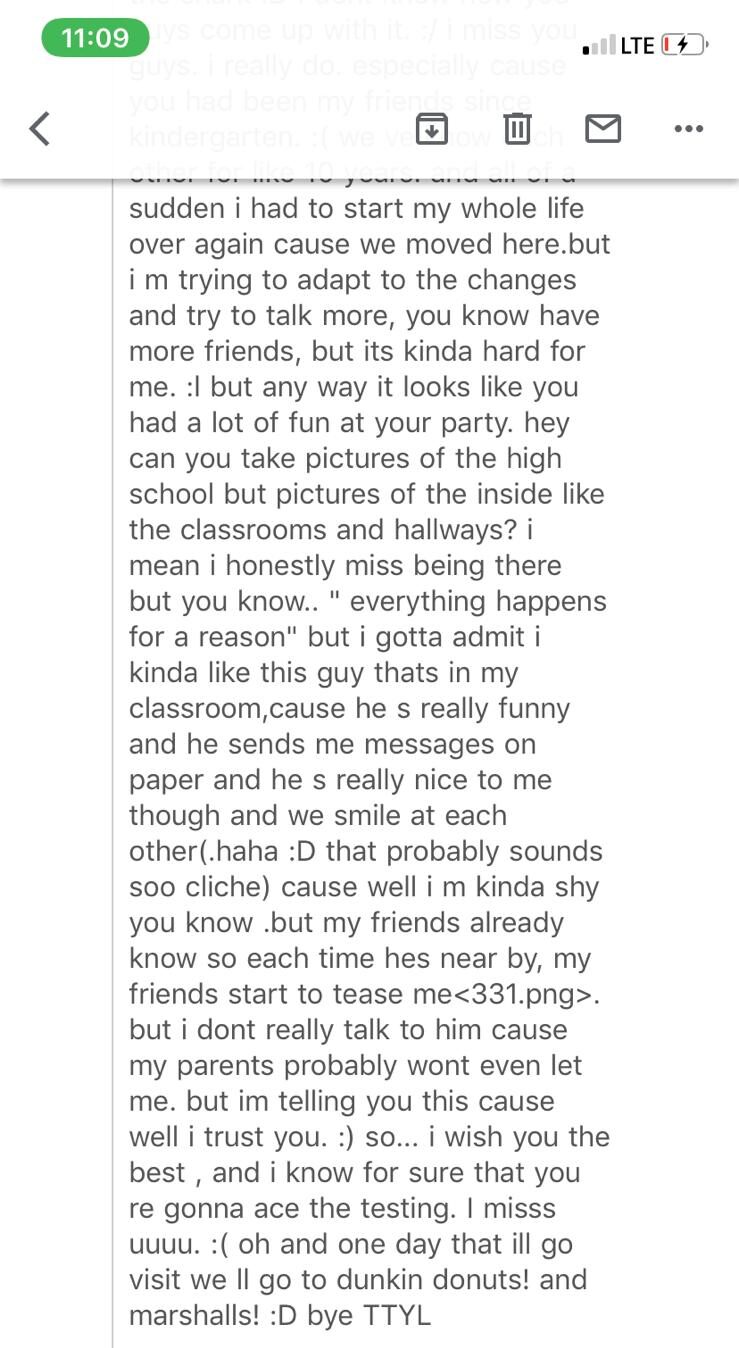

Although her high school was the space where she spent most of her time, she never felt like she belonged. When she first visited the school with her mother to submit her enrollment materials she thought she was visiting an administrative office, as the simple stucco rooms located on an arid piece of land with stray dogs wandering in and out of the front gate did not elicit her image of a high school from growing up in the United States. She wrote to her best friends in New Jersey and shared some of her struggles… “I had to start my whole life over again cause we moved here. But i m trying to adapt to the changes and try to talk more, you know have more friends, but its kinda hard for me.” She also kept in touch with them about their high school lives in the US, such as sweet 16 parties, boys they had crushes on, the pressures of standardized testing in US schools, and everyday things Alondra missed like dunkin donuts and marshalls. She also longed for the familiar structures of US schools and asked her friend, ‘hey can you take pictures of the high school but pictures of the inside like the classrooms and hallways? i mean i honestly miss being there but you know..”

On her first day of high school in Mexico she realized most students already knew each other well, and—as someone who had not grown up in the same town, state, or country as them, they saw her as different. In fact, they interpreted her stronger abilities in English rather than Spanish as arrogance. And she faced bullying, particularly by other female students, during her high school years. She described a female student who went beyond verbal insults to being physically aggressive with her and how she responded, “And I feel like that I, since I’ve been bullied all my life, when she tried to do that I got aggressive. Like I have that idea that I didn’t want to be bullied anymore. That I wouldn’t let her do anything against me, and I think that affected me a lot.” Alondra did make one close friend, Rebecca, who had recently lost a sibling to suicide. They spent most days after school together and when Alondra felt upset she longed for the close female friendships like she had had with her best friends in New Jersey. She still kept in touch with them, but less frequently, as their realities as teenagers felt more and more different as time passed.

Alondra also felt uncomfortable around many of her male classmates, who made suggestive comments to her and others and were rarely punished by teachers. Alondra intentionally sat at the back of the class to avoid their attention, but many teachers made students walk to the front of the room to turn in homework assignments, which required squeezing past students’ desks that were tightly packed into their small classroom. Often Alondra opted not to turn in her assignments, deciding she preferred to accept lower grades rather than enduring her classmates’ stares or comments. Her teachers worried about her but didn’t know what to do—they felt she was too shy, and had to get over it if she was going to succeed in the world. As she did not trust them enough to let them in, they wrongly assumed she was indifferent about schooling and about her academic future.

MAKING ROADS

THE SEARCH FOR HIGHER EDUCATION ACROSS BORDERS

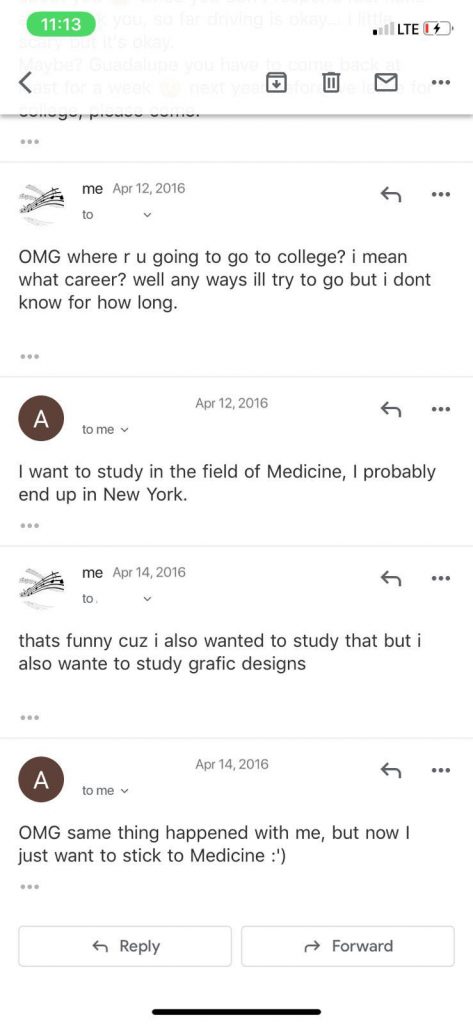

She successfully graduated from high school and unlike many of her classmates, Alondra aspired to pursue higher education. She did not want to get married or have kids or become dependent on her spouse for money. She regularly discussed careers that interested her— becoming a graphic designer to extend her tremendous artistic talent, learning about mechanics although she worried about the sexism present in most work places, or becoming a nurse—which her parents wanted but she was less excited about. In emails with her best friend from New Jersey she learned that they had similar career interests and that Alison planned to study medicine in college in New York. Although Alondra had similar aspirations, money for college was the main issue. In her small town at the foot of a volcano, there were very few scholarships or a national loan program in Mexico to pursue education in ways that are more common in the United States. Although her teachers did not see Alondra as interested in continuing her studies, this was a central goal she had in her life, but her family’s limited economic resources from moving to Mexico and the lack of pathways for scholarships or loans meant that her options were very limited. As she transitioned into her post-school life, her trajectory differed greatly from her friend Alison who had stayed in the US, and who was able to access scholarships to pursue a career in Medicine.

? qué carrera quieres cursar?

Quiero estudiar medicina ❤️

Searching for Higher Education across Borders

After graduation Alondra joined a rural teaching apprenticeship program in which she learned to teach in a small town, which would then provide money for her own future studies after a one year commitment. Yet after several months living in a small town in bordering state, disconnected from her loved ones because of the distance and lack of cell phone signal in her new rural setting, she decided to leave the program. She then found work at a local store, but realized quickly that earning less than $10 a day was not going to be enough for her to save up and afford further studies. She then moved to the state capital and began working at an English-language call center, taking advantage of her strong English-speaking skills. Although this was a much better paying job, she became frustrated with the verbal mistreatment she often received from customers and decided to look for a new option.

One year after graduating from high school, when she was 19, Alondra decided to move back to the United States, to New York City where two of her uncles lived. She stayed with them and, as a US Citizen with official papers, easily found a waitressing job. She didn’t move to the US because she wanted to be there—she preferred to be in Mexico, with her parents and sister. Yet economically the employment opportunities were much more limited in Mexico, and she doubted a job there would let her save up enough money to pursue further studies and a career. Whenever she can she flies back to Mexico to visit her family, a privilege her parents are not afforded without US Citizenship. Her current plan is to join the Army, which would be a 5 year commitment, but would help her establish a career in nursing.

Understanding Binational Students’ Experiences

Alondra represents a common childhood migration experience that is often overlooked— children born and raised in the US to Mexican immigrant parents who relocate to Mexico directly or indirectly due to immigration policies. These migration experiences tend to be overlooked in our larger immigration narratives portrayed in the media, and thus erase the experiences of students like Alondra. Although Mexico has experienced an unprecedented increase of binational students enrolling in their schools, few structures or policies have been put in place to support these students or the teachers who work with them. For example, Mexican teachers rarely receive training to work with students who bring different linguistic resources or knowledges to their classrooms (such as those Alondra developed during her first 10 years of schooling in the US) and the schooling system is largely designed for monolingual Spanish speaking children who have grown up in Mexico. Because of educators’ lack of experience working with binational students, they often misinterpret children’s practices in deficit ways.

She was regularly misunderstood at her school. Alondra’s less than perfect handwriting was seen as laziness rather than an orientation to schooling from her upbringing in the US where the content of her assignment was much more important than the neatness with which it was presented. Her hesitance to turn in homework assignments was a strategy to avoid male students’ unwanted attention when she had to walk in front of them to the teacher’s desk, not indifference toward her schooling. Her teachers saw her withdrawn behavior as an intensive form of shyness that they feared would paralyze her future educational and career prospects. Educators assumed her future aspirations were about starting a family and not a career. Yet, as Alondra’s mother poignantly noted, her daughter is extremely valiente, or brave. She moved to a remote small town to try out a teaching apprenticeship, and then to a large city on her own to work in a call center. She then made the decision to move across the border to seek out better job options in the US that would open up possibilities for future studies.

In Mexican schools Alondra also received regular messages that she didn’t belong. Teachers often told her she was better suited to live and learn in the US, where she was born and raised. Although they never meant this in a malicious way, these constant comments sent a message to Alondra that she didn’t belong in Mexico. Everyone regularly assumed that Alondra would prefer to live in the US, and often celebrated her decision to move back for work. Yet Alondra did not live and work in New York by choice—she carefully navigated the opportunities she had between her two countries of residence and made painful sacrifices to be away from her family in order to access the work opportunities she hopes will pave the way for a better future.

Interconnection of Immigration and Education Policies

When we talk about education policies and practices, we rarely touch upon questions related to immigration. Indeed, most educators are unsure of how to broach the topic of immigration in schools because they worry what they say or do could endanger their students or their own careers. This is not out of malice, but because we do not support educators to understand the realities of immigration policies in the United States or in Mexico. Yet binational students’ experiences, such as Alondra’s, bring to the forefront the interconnections of immigration and education policies. The fact that there are unprecedented numbers of children with US-schooling experiences now enrolled in Mexican schools directly relates to the deportation-based US immigration policies under the Obama and Trump administrations. The current administration’s clear attack on immigrants, especially those from Mexico and Central America, only heightens the importance of working to understand the intersections of immigration and education policies. Although schooling is often seen as a mononational project in which we rarely consider students’ learning beyond our own national borders, Alondra’s trajectory shows the importance of working toward binational conversations about schooling for the young people who so gracefully navigate life and learning on both sides of the border.

BY THE NUMBERS: LEARNING HOW TO RETURN

PEOPLE RETURNING TO MEX FROM THE US 2005-2010

PEOPLE RETURNING TO MEX FROM THE US 2009-2014

THEY BEGAN STUDIES IN THE US AND ARE NOW IN MEX

Why Is it Important?

The need to guarantee continued access to equitable schooling for hundreds of binational students is often overlooked, and is necessary if we aim to create true spaces of belonging and inclusion. Young migrants moving from the United States to Mexico face major barriers: family separation, limited social networks in schools, and being pushed out of schooling. There are also substantial administrative barriers in place from those in charge of education in Mexico; the school, which should be a space for learning and fun, can become a space of exclusion for young people and families that return. The lack of resources and support networks for students hinder their ability to graduate. In addition, many students have to learn academic Spanish and build relationships in a different cultural context. Many opportunities exist to improve the experience of children returning to their parent’s country and it is essential to support them.

What Is the Situation?

South-North migration during the last 20 years has occurred as follows:

Almost 1.4 million people migrated from the United States to Mexico between 2005-2010

About 1 million people left the United States during the 2009-2014 period.

The height of migration from Mexico to the United States occurred in 2007, with 12.8 million Mexican nationals living in the U.S.; since then, this number has also declined.

Currently, there are limited educational programs, in the United States or Mexico, that provide tools for teachers to address the needs of binational students.

It is estimated that at least 500,000 children with schooling experience in the United States are now registered in Mexican schools (data from 2016). Most of these children are US-born citizens with Mexican national parents: and intense deportation policies are the primary cause for binational children’s relocation to Mexico.

Migration and Binational Schooling

The Binational Context of Students We Share

More Mexicans Leaving Than Coming to the U.S

How to Get Involved

Given the recent migration policies of the Trump Administration, it is essential that we look for ways to support young people raised in the United States who are returning to the country where they or their parents were born. Citizens on both sides of the border need to learn more about the realities of return migration to better understand how to support binational students. Welcoming binational children and including them in the decision-making process regarding their education is crucial to create multicultural, open societies.

notas al pie

-

Ana González-Barrera (2015), “Migration Flows Between the U.S. and Mexico Have Slowed – and Turned Toward Mexico”, Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends, https://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/11/19/chapter-1-migration-flows-between-the-u-s-and-mexico-have-slowed-and-turned-toward-mexico/

-

Roberto G. Gonzales (2015), Lives in Limbo: Undocumented and Coming of Age in America. Berkeley, California, University of California Press.