The earth becomes an orphan

The coming and going of Ecuadorians from the Austro to the U.S.

“The earth becomes an orphan,” said Aída thinking of the effects of emigration on Azuay, Ecuador, the province where she was born. “Grandmothers also become orphans.” She reflected, “They lose children of their own, and later they will lose their other children, their grandchildren, whom they cared for. They are the children of their children that went to the United States before and now they ‘send for them’ so they’ll also migrate”. That chain orphanhood—mothers that lose their children; children their fathers, their mothers or both parents; grandmothers that lose their grandchildren; and whole communities that become deserted—, has left an imprint on the rural and urban history of the Ecuadorian Austro. This region, located on the southern range of Ecuador, is formed by the provinces of Azuar and Cañar. Men and women have steadily migrated from this region to the United States since at least the end of the 1960s.

Aída is 33. Though her only daughter is seven, she learned to be a mother at the start of adolescence.

“My older sister played the role of the young mother. She helped my mother, who minded for the children of my migrant siblings. Later, when she left, it was my turn”.

Aída 33,years old.

Aída was only 14 when she became the caregiver of her niece and nephew, both less than five years old, whose parents had migrated. Aída and her mother, Doña Leonor, shared the tasks of taking care of the children. Aída’s mother oversaw the home economics, the work in the chacra (farm), and sales in the central market of Gualaceo. Aída,

“[…] had other tasks. I made the food, washed the clothes. We went to school together because the three of us were studying. I would sing to my niece and nephew. I played with them, or we celebrated their birthdays.”

Aída 33, years old.

Meanwhile, Aída grew up and started living with the absence of part of her family. She missed her migrant siblings but spoke to them on the phone once a week, when they called their children. Later, with the internet on her cellphone, Aída could even see them. Those virtual meetings, she said, “help, they always help to forget, even for just a while, that they’re not here anymore.” The sorrow and pain her mother carried for living far from her children also accompanied her in her day to day life. Though with time, Leonor got used to the physical absence of her four children, she always missed them more, and the pain also grew more each day: in 20 years, Aída’s four siblings, still undocumented, could not return to Ecuador to visit their mother. And although Aída shared Doña Leonor’s anxiety because her grandchildren were growing without parents, she knew that her niece and nephew, young as they were, slowly soothed the pain of that absence. “My niece and nephew,” said Aída, “even though they didn’t have a father and a mother, had other mothers, and different types of mothers, and that helped them forget the pain of being far from their parents, my migrant siblings.” Thus, those who stayed, invented a new life in Dotaxi, the indigenous community where she was born and grew up in in Azuay. In the midst of the orphanhood that migration causes, they recreated a life that lasted until the nieces and nephews left to undertake the journey themselves. Paying “coyotes” [immigrant smugglers], her siblings sent for their two adolescent children that also left by the pampa. Since then, Aída and Doña Leonor, who is now 70 years, have reinvented their lives to cope with another pain a new absence has left them: that of the two children they both raised, the grandchildren and the niece and nephew who are now gone.

Aída’s history multiplies itself in the Ecuadorian Austral. Like Aída, Angélica, who just turned 18, takes care of her nieces and nephews in Gualaceo. In the same way as Doña Leonor, Doña María Rosa, Doña Beatriz, Angelita, Doña Rosa, Doña Julia, and Doña María are also orphans, they live an inverted orphanhood, they are childless. They care for their grandchildren and are also waiting for the day when they will choose to emigrate.

Many other unmarried mothers, grandmothers, sisters, and aunts take care of hundreds of children and adolescents, daughters, and sons of migrants that remained in Ecuador. Without them, the life experiences of those children and adolescents who grow in the absence of their fathers, their mothers, or both parents, could not be completely understood. Those children and adolescents reinvent themselves in the absence of their parents and decide later on if they leave or stay with their relatives, their caregivers.

Keepers of the Migration Memory

Keepers of the Memories of Migration

Women and men go from Dotaxi to Long Island. From Mayantur to Brooklyn. From Jima, from Gualaceo, and from Girón to Queens. For more than five decades, different people get into debt of at least 10 000 U.S. dollars to pay the coyotes, crossing seven borders, traveling through Mexico and swimming in the River Grande, thousands have left their country of origin, Ecuador, in an attempt to have a different life, a better experience.

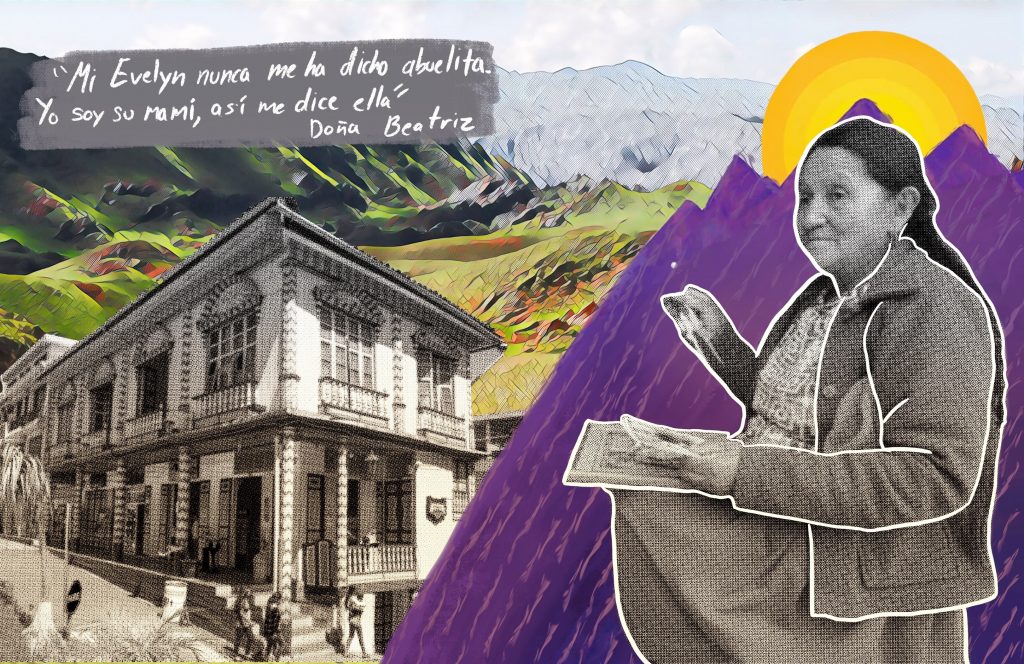

Doña Beatriz is 67. She is a peasant living in Cochapamba, another indigenous community located in the Azuay Province. Every day she works the land, sells produce in the market and she also takes care of children. Her daughter, Neiva, left for New York when her grandchild was one year and seven months old. Her departure was not the first in the family: previously, her husband, her compadres [godfathers of one’s children or parents of one’s godchildren], her siblings and nieces and nephews had left.

I remember they started leaving when I was 30. The first to go was a young man from Mayantur. Then two sons of my godfather. The males left first, then the women. They all went by the pampa. They told harsh stories when they crossed the river up there; I think it was in Mexico. Now they take the guaguas [babies]. They bring them with them when they are small; some want to leave, the others think it better to stay, but then they grow, and everyone goes.

Doña Beatriz, 67 years old.

Doña Beatriz’s account repeats itself among the other caregivers. Immigration crosses their lives ‘ histories. Their husbands, fathers, brothers, daughters, mothers, brothers in law, friends, neighbors, nieces, and nephews, and their children have left. They left to transform their precarious living conditions. In fact, in some cases, even the caregivers had to go. But they came back or were returned by the migra [immigration authorities] and never attempted to emigrate again. In their stories, departure is constant.

In contrast, the return of their loved ones seems like an impossibility. At least that’s what Doña Rosa, 65, asserted. She is another caregiver also from Cochapamba, who was left to care for her granddaughter from the time she was born, and since her daughter left 11 years ago:

Without documents, without a visa, you tell me. How can they come? They can’t. They leave and don’t come back. And if they return them, they return them like prisoners. They come back quickly; they don’t stay there. It was like that with my daughter. There was no work here, and she tried leaving several times. When she got there, she stayed and has never come back, and never will […] Here I’m thinking all the time, every day, I always think of her.

Doña Rosa, 65 years old.

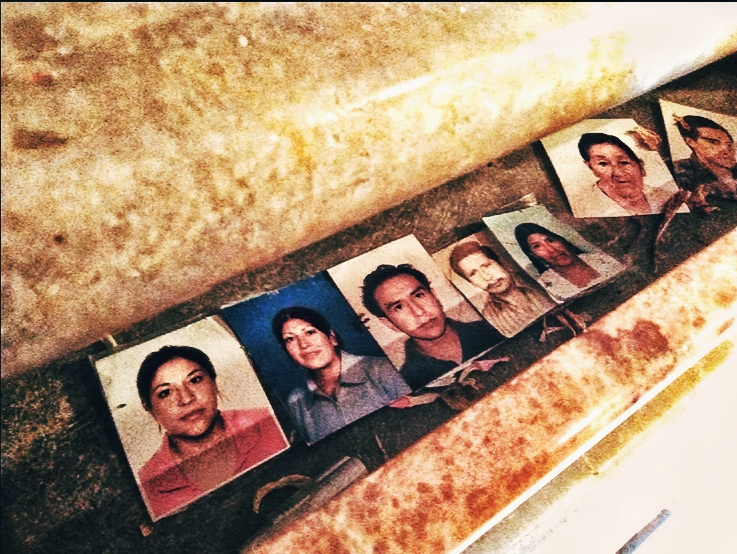

When facing the pain caused by this absence, like Doña Rosa, the rest of the caregivers think of those who are no longer there, they reminisce about them, and they bring them to the present with each story. For this reason, they take great care of their memories and the few photographs they still have, and that illustrates their stories. Thus, they gather stories about their lives. These stories are the stories of their families. They collect stories and memories of Ecuadorian migration. These women don’t forget that poverty triggered the departure of their loved ones. Nor have they forgotten how each of their sons and daughters, or their husbands, or their siblings departed. They always remember the last goodbye.

They recount what they used to hear about how migrants went by ship from Ecuador to New York, bypassing Mexico. They know how the route has changed. How today you must travel by land to Colombia, to Peru or Bolivia, and from there to Central America. They recount how before you had to cross all this to reach Mexico and how now it’s easy to arrive there by plane because, since 2018, Ecuadorians no longer require a visa. They know stories about coyotes, of smugglers, of forgers of visas, of enganchadores [labor contractors] and chulqueros, local moneylenders that lend thousands of dollars to immigrants to cover the cost of the journey. These women know many stories of deceit on the migration route, as well as stories of successful arrivals at the much-desired northern destination.

The caregivers know what happens at the borders and the clandestine crossings because they are told and remember many stories. They know whom to pray to: Our Lady of the Wayside, the Señor de Andacocha, or the Infant Jesus of Prague. They also know when to join a procession or leave offerings during mass to pray for the protection of all the people who will emigrate. They know the stories of shipwrecks of Ecuadorian immigrants; stories of those who have died at the border or the ones that disappeared and never returned. Those stories would seem forgotten by a society that doesn’t acknowledge how chain orphanhood is a historical feature that constitutes and determines this society. But caregivers are unwilling to forget. They cannot forget their children or their husbands, who are no longer there. They also are unwilling to let their grandchildren forget their migrant mothers or fathers. Hence, they tell these children and adolescents who their parents were, why they left, where they are. Yes, these women, the caregivers, are unwilling to forget. Their unwillingness seems like an outcry in the night for the loss of the vital presence of their relatives and loved ones. Not only because their loved ones are no longer physically there, but because in many cases, they died in their attempt to emigrate. Remembering, yes, remembering, they preserve the memory of their dead. That’s the story, for instance, of Doña Julia, 60, a caregiver in Girón, an urban parish in Azuay. She was left in charge of the two granddaughters since her daughter and son in law died on the route:

My daughter was 20. One day she told me: I’m leaving mommy, I’m going. It’s frightening, yes, and you pray to God to protect them. You don’t even think that something terrible can happen to a daughter […] She left me her two young daughters: one three the other a few months old, newborn. I learned after that she and her husband had an accident at the Chiapas crossing. I’m not sure where that is, I think, near the border of Mexico and the United States. What sorrow that was. My little daughter died and didn’t come back.

Doña Julia, 60 years old.

Who knew where, on the map of the American continent, Chiapas is. Doña Julia didn’t care. What mattered was to confirm that “up there,” as she said, where widespread violence along the Mexico-U.S. border is perceived more sharply, her daughter died there. At the same time, the grief that Doña Julia bears confirms that the violence is not as far from the Andes, not so up there, as you think. Violence at borders, violence towards immigrants, has had and still has an impact on the lives of people like this caregiver. Like her granddaughters, who became orphans when their father and mother attempted to pass through Mexico, what Doña Julia cared the most about was to know where the body of her dead daughter was. Tearfully she remembered that after months of unceasing searches, she eventually found her. In this process, she did not receive any help from any institution of the Ecuadorian State. When it came to the death of her daughter on the journey, there was only silence. When it came to her two granddaughters being orphaned, there was only silence. Her neighbors, some relatives, and acquaintances of those neighbors, were the ones who helped and guided the search from a distance. In essence, she, a native of Girón, from an urban parish in the Ecuadorian Andes, tried to locate in Mexico, the body of her dead daughter. While she thinks back to this search process, her profoundly sad gaze combines with a gaze of unyielding fortitude bestowed to her by the granddaughters she has taken care of for 14 years.

The story of silence and oblivion is also the story of Angelita, who at 32 became a widow responsible for five children. It was in 2005 when the ship his husband sailed away on, with a hundred other Ecuadorian migrants, was wrecked on the route from Ecuador to Guatemala.

He left one Wednesday at two in the afternoon. He said goodbye to me. He told me: “Take care of my children, never abandon them. If I’m leaving, it’s to give them better days”. I stayed with my young children, and like me, 60 mothers stayed alone with children and debts. One could hear loud moaning. We cried so much. But they never gave us an answer. Nor did we get help from anyone, we alone gave our children a proper upbringing.

Angelita, 46 years old.

Unlike Doña Rosa, Angelita could never locate on the map of the American continent the body of Ángel, his dead husband. The Pacific Ocean took him away along with more than one hundred immigrants that were shipwrecked. How many thousands of Angels have been lost in the maritime routes connecting Ecuador and Guatemala? How many hundreds of Ecuadorian children and adolescents, kids of immigrants that were shipwrecked, grow up without anybody knowing their story? If migration has left an imprint on Angelita’s memory, one of those 60 mothers, and on the rest of the caregivers, it’s because, in Ecuador, her country of origin, the departure of their sons and daughters cuts through the historical memory.

For five decades, generation after generation of Ecuadorian men and women have migrated. Despite being a small country located in the Andes, with around 17 million inhabitants, estimates indicate that approximately 3 million Ecuadorians, or 17% of the total population, live outside of the country. One can explain Ecuadorian emigration by its single-product economy, highly dependent on the international market, and the unceasing systemic poverty and inequality in the country. In fact, in Ecuador, poverty has found a niche in farm and rural life to spread rampantly. In 2018, 43% of people living in rural areas were impoverished, while in urban areas, only 16% were. Also, in rural areas, 74% of the people are employed in the informal sector, compared to 26% in urban areas. Thus, it is not a coincidence that to avoid and fight against violence related to poverty, men and women, particularly form rural areas, have emigrated, mainly to the United States, the primary migratory destination for the Andean country. By the chacra, by the pampa, by the road, with counterfeit documents, with a visa, without a visa, they have traveled to that destination in such quantities that today 738 000 Ecuadorians live in that country and are the tenth largest group of Latin American descent.

This unceasing exodus has had inexorable effects on the children and adolescents of Ecuador. According to the latest census in 2010, 37% of the migrant population left behind sons and daughters in Ecuador under the care of immediate relatives. Data from the Observatory for the Rights of Children and Adolescents confirm that 2%, accounting for more than 200 000 children and adolescents, have at least one parent living abroad. Thus, a considerable number of Ecuadorian children and adolescents have stayed in the country and lived with other family relatives. These relatives are mainly their grandmothers or aunts, their caregivers. They live in transnational families, and these children and adolescents may later emigrate to reunite with their migrant fathers and mothers in the United States. This practice is a constituent element of the historical memory of the primary migrant-sending areas, like the towns in the Ecuadorian Austral.

The Caregivers

Among those Who Stay and Those Who Are No Longer There

In a country characterized by chain orphanhoods caused by emigration, the role of the caregivers has been defining the lives of thousands of children and adolescents that have stayed on and will continue to do so. Caregivers like Aída, Doña Leonor, Doña Beatriz, Doña Rosa or Angelita, and women of all ages. They are 14, 18, 33, 43, 48, 60, 67 or 70 years old. They are widows, married, single; they are also divorcées. They are the mothers, the aunts, or the sisters of migrants. They live in indigenous communities in the rural areas of Jima, Dotaxi, or Cochapamba, or the peripheral neighborhoods of Cuenca, Girón, Gualaceo, and other cities in the Ecuadorian Austro. Some of them finished primary school, others, high school. They are bakers. They are peasants. They farm the land. They start working in the early hours. Some go to Cuenca to sell bread. Others to Girón to tend their fruit and vegetable stalls or sell juice in the market. There are still others who work from a very young age in the chacra and in housekeeping.

They pray for their children. They beg the Virgin to take care of them. Every year on September 14, they go on a pilgrimage to Guachapala to reach the temple of the Señor de Andacocha, patron saint of migrants. They light candles for him, and they pay offerings, they leave written messages asking all travelers to be safe and protected. They leave photographs with the names of their children written, so he takes care of them during the journey. They care for grandchildren, nieces, and nephews. They imagine their children making buildings in Manhattan. They listen to their daughters when they are walking in Long Island. They look at pictures of them. They gather memories. They cry. They shed tears when they recount the day their children left by the chacra because they had an outstanding debt of more than 10 000 dollars with the coyote. They weep because their sons told them they would be back in a year, and 25 years have passed, and they haven’t returned. They sob because their children said they would build a house and would come back, and it is ready, but empty, because they can’t return. They cry because they never knew if their children ate, were scared, or were cold when they traveled the road. Others cried for their dead husbands or brothers, for those who disappeared, for the bodies that never arrived.

They recall the stories on the road and stop talking because they know that in the sea, their children are at risk of being shipwrecked. They know that they can become victims of assault along the route. They also are aware that the small sticks and stones on the Mexican border are small bones and heads of other peregrines like their sons or husbands, that have died trying to migrate. That’s why they don’t want to talk anymore. They speak in silence, with their eyes. A gaze emerges ridden with grief from the absence and the strength of a presence in their lives: that of the children they raise, their grandchildren.

They keep praying for their grandchildren not to feel grief. They cook morocho [spiced corn pudding or drink] and colada [oatmeal drink], so they go to school with food in their stomachs. They arrive on time, and they almost are never delayed after-school. They iron their uniforms. When they can, they check their homework. They are their children and grandchildren’s representatives at school. They talk to the teachers, but they don’t hear them. The teachers do little to help their grandchildren, their nieces, and nephews or their children, the children of migrants. There is no help at school. There are no programs. There is no reading, anything that explains the orphanhood migration causes. They speak to their children and, through slim digital screens, meet their new grandchildren born in the Yoni (the United States). They cry again, but in a flash, their tears become smiles when their grandchildren’s eyes meet theirs; and when a hug from the children of their children who are no longer there, that won’t come back, fills the void of grief these women bear. And they don’t stop praying to stay healthy, so they can keep taking care of the children.

Taking Care of Those Who Stayed

The daily life of caregivers in the Austro

Aída, Doña Leonor, Doña Beatriz, Doña Julia, Doña Rosa, Angelita, and the other caregivers repeat that their grandchildren, their nieces, and nephews, and their children are orphans. Indeed, those children and adolescents they take care of, as children of migrants, grow up without their fathers, their mothers, or both parents. In some cases, de facto orphans, because their folks have died on the road, like Angelita’s children or Doña Rosa’s granddaughters. But somehow this orphanhood mutes and transforms, and this is due in considerable measure to the caregivers.

The word “care” derives from the Old English carian, cearian “be anxious or solicitous; grieve; being concerned or interested.” It is a word that registers an action that requires attention, dedication, and effort. Every caregiver from the Austro thinks of her ward. She pays attention, dedicates time and energy to her nieces and nephews, her grandchildren—the children of her children that have left. This care began when they entrusted these children and adolescents to them. Grief takes hold of their voices when they recall the departure of their loved ones to the United States and their farewells. But the sadness hides because they remember that their grandson or their nephew remain in their care. They had to explain that they would grow in the absence of their fathers, mothers, or both parents.

For this reason, they had to invent stories to help these children and adolescents to, in some way, appease the grief unavoidably caused by absence. Doña Leonor recalls:

The boy used to tell me: My mommy isn’t coming. And I told him, she is coming soon, my dear, she went to Cuenca to get candy, and the car broke down, I said to him. He knew how to go to the side of the road and repeated: “The car broke down,” “the car broke down.” So, he grew up.

Doña Leonor, 70 years old.

Aída used games and singing as a mechanism to induce oblivion: “I made them play a lot so my niece and nephew would tire soon and wouldn’t remember […] Then, at night, I’d sing to them so they wouldn’t ask questions and sleep peacefully”. Doña Julia decided instead to narrate the departure in another way:

They were left without their parents when they were very young. That’s why they grew up thinking I was their mother. That’s what they called me and still call me “mommy.” Then, at school, when they were older, they asked for their parents. I never lied, but I told them slowly that they had an accident and left here. I think they understood.

Doña Julia, 60 years old.

Care begins with the way we recount, with the way we reminisce. That careful and imaginative way of sharing helped these grandchildren and nieces and nephews to understand their grief, and to forget. If the caregivers agree on something is that the smaller the sons and daughters of migrants, the faster they forget the absence of their parents and the less grief they must endure. Angélica is 18. Since she was 13, she has been in charge of her nephews, 6 and 4. They all live in Gualaceo, and she reflects: “Taking care of my nephews was not nice at first because they cried with sorrow for their mom, they cried and cried. But then, since they’re young, they just forgot”. Doña María Rosa is 45, and she is a peasant from Jima, an indigenous community in Azuay, she shares this same thought. When her husband migrated, she oversaw children. The younger ones “didn’t even feel it, or felt it a little,” she says, but “the oldest girl got a nervous condition, or maybe it was grief because the father left. She lost a year in school because she didn’t recover, and she is still ill.”

Adolescents are perhaps more aware of the orphans created by migration. They know of the dangers on the route and that the journeys to the United States are not short; many involve not returning. They suffer for this, and it’s more hurtful to them. They also feel a resentment that seems to grow as they mature. “When he was a young boy, he liked talking on the phone with his mother, who used to call him once a week from a house in Gualaceo. When he grew up, the mother called him. But he didn’t want to speak to her; he’d say: “No, mommy, you talk, and he didn’t even speak to her,” Doña Beatriz recalled that about the problematic relationship between her adolescent grandchild and his migrant mother. The care they give thus begins in the grief of others, their grandchildren, nieces, and nephews. They try to reduce for them the burden of sorrow, or they share their pain to forget if they can while they grow up. But it’s not always possible, and they know it. That’s why they take great care of them.

“My Evelyn has never called me granny. I am her mommy. That’s what she calls me.”, insisted Doña Rosa, while Doña Beatriz repeated, “she only calls me my mommy.” It’s no coincidence that these sons and daughters of migrants call them this way. From the time they are born, many are left to their care, and others have a vague memory of their parents. However, their caregivers play the role of mothers, or mothers and fathers at the same time.

Taking care of them means waking them up, dressing them, making food for them, taking them early to school on the bus. It means having clean clothes ready for them, waiting for them after school, bringing them back home. It’s withdrawing the money their fathers and mothers send, paying the school fees, spending the money they send to them. It’s taking them every Sunday to talk on the phone with their fathers or mothers, to be sure they always remember them.

Taking care of someone is also assuming the responsibility of overseeing another person’s child, that get ill, that grow and complain, of children that demand answers that caregivers don’t always have. Looking after them means helping other people’s kids to understand that not all children of migrants have somebody who takes care of them. Looking out for them means listening to the stories they bring from school from other children and adolescents that, like them, don’t have any food, don’t keep up with their homework or lack money because their fathers and mothers have left, and their caregivers don’t take care of them. These stories repeat themselves in the Austro, and caregivers make sure their children from other parents understand why this happens.

They have their children from other parents so much in their minds that they care for them and dedicate time and effort. These women are so present with these children that the potential feeling of being orphaned seems to transform for these sons and daughters . They are grandmothers, aunts, and sisters that become mothers, that become fathers or mothers and fathers of the sons and daughters of migrants. Though they grew up without their folks, like Aída said, the care that each one of them received helped to “assemble a personal jigsaw puzzle of what a family is,” and that can be achieved only through care. Thus, they are children and adolescents who create and recreate other families with several “mommies,” where grandpas are “daddies” or where the absence of their fathers and mothers have been with them during their development.

The Departure of Other Persons’ Daughters and Sons

When those who stay finally leave

Because they are children of their children, or children of their siblings, or even children of their own, but mainly they are children of migrants, their caregivers, know that they can leave at any given time. Sometimes they leave because their fathers and mothers send for them to finally reunite with them, usually in New York,after years of absence. Sometimes, they leave because those boys and girls grow up and decide for themselves to emigrate.

Send for means paying a trusted coyote to bring their sons and daughters through the chacra. It also means that caregivers must hand over their grandchildren or nieces and nephews to enganchadores or the coyotes themselves for these individuals to take them away. It happened to Doña Leonor. One day her son told her he had the money to send for his children:

When they wanted to take them, they didn’t want to go. I don’t want to go, he told me. They cried, and I cried with them, but I had no alternative but to deliver them. My kids left with a phony visa. I took one of them to Ibarra and the other one to Quito. I only prayed and prayed, and cried, what a deep sadness. My children left.

Doña Leonor, 70 years old.

Doña Leonor’s grandchildren left Ecuador for Mexico and from there to New York. They were just 15 when they departed. They “didn’t want to go,” as she says, and that situation repeats itself in the stories narrated by other caregivers: “My daughter wanted to take him, but my grandson didn’t want to and didn’t want to. And didn’t leave. He only said I’ll go only if my mommy, meaning myself if I went with him, and I wasn’t leaving”, recounts Doña Beatriz. And they don’t want to leave, and they don’t leave because they are very attached to their caregivers. Only imagining that grief has prevented the departure of many sons and daughters of migrants, because even if their parents send for them, they simply decide not to leave. Others, in contrast, like Doña Leonor’s grandchildren, go eventually. Because of the departure of their grandchildren, of other persons’ children, immense grief swamps the caregivers, because from living in an inverted state of orphanhood, from being childless, they pass into a situation where they lose their grandchildren, other parents’ children that became their children.

When my niece and nephew were going to leave, my mommy didn’t want them to leave, and they didn’t want to leave. But we had to tell her: “Mommy, they are not your children. You have to let them go.” And they left. We discussed with the children: “You are going to be okay; you are going to see mommy; you are going to see daddy. And you are going to be happy. And you are going to have the family that you have drawn with your colors. And they left.

Aida, 33 years old.

Aída’s story serves as testimony of what happens when those who stayed leave: they leave the rooms, the squares, the schools, the houses, the neighborhoods, and leave the fields empty and silent. The caregivers are also abandoned, without the love that has sustained them and given them life. Many times, they feel blue, they say, because of the grief, because they have devoted themselves to the care of these children and adolescents that are no longer there. Sometimes they get ill from grief because sadness lingers and visits some months more than others. When the children of migrants leave, says Aída, “absence comes here and sticks to everything.” Gradually the absence starts to disappear. The stories and virtual contacts with grandchildren, with nieces and nephews that slowly discover what life is like in New York, also help to fill the absence. “We talk on the internet, and we see each other. With the internet, the only thing we can’t do is touch each other. If the thing is to laugh, we laugh; if it is to cry, we cry,” says Doña Leonor, and proceeds, “grief transforms, but it never leaves.” And it doesn’t leave because of the grief of being far from her children, the children of her children, she and Aída raised.

Many of the caregivers would want to emigrate, “but just to visit,” they say. They would like to visit their children, their grandchildren, their nieces, and nephews. Others, in contrast, like Angélica, are ready to depart, leaving through the pampa and paying a coyote. She has a one-month-old daughter. She will probably remain under the care of Angélica’s mother, like her nieces and nephews, when her sisters left Gualaceo for the Bronx. Others say they will apply for a visa, to maybe “emigrate to visit,” and then return, but they doubt the visa will be approved. All of them coincide in that “Government permits” should disappear, like Doña Beatriz states, because only like that, people can go and come back.

The stories of caregivers are the stories of thousands of Ecuadorians that have left. Ecuadorians that come back, are sent back, and that have returned to the United States. Their stories constitute a critical piece to understand the life experiences of the Ecuadorian children and adolescents that stay. Caregivers are not only in the Austro; they are in many other towns in Ecuador, and Colombia, Brazil, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, and even in the United States. They look after children; they take care of them and our memories. For this, we should never forget their voices nor stop understanding and remembering their stories. The stories of orphans that migration leaves behind, are our own stories. These are the stories that leave an imprint on the lives of the sons and daughters of thousands of migrants.

This space makes me feel calmer because they show consideration, and ask me how life was, my life. I unburden when I talk.

Doña Rosa, caregiver in Cochapamba.

Aída: The Imagined Route

Aída, 33, is not only a caregiver of those who stay; she is a sister of migrants, a niece, a cousin, a neighbor, a friend of migrants. The departure of her acquaintances and her relatives 0has marked her life and her memories. Thus, she keeps stories, many stories, about the route, the crossings, the road. She recounts that since she was very young, she listened to her mother, to her aunt, to her neighbors talk about what their migrant sons and daughters told them about the journey. In her own voice:

Since we were kids, we heard that people left passing by the road, and they arrived. Me, like many others, since we all grew up here, I thought that going to the Yoni (the United States) was like a dream: you fall asleep, and you wake up there, as easy as that. When you’re a kid, you grow up like that, with that idea or illusion that getting there is very simple. And from a very young age, one doesn’t gauge what the route really involves, and this happens because they don’t tell you about it.

Aída argues strongly that from a very young age, the only thing she knew was that her brothers, cousins, or neighbors had left for the United States and had arrived at that destination, nothing else. The details of the journey and the types of violence were utterly unknown to her. And this was because, as she states herself:

(…) they don’t speak of violence on the road. They talk about arriving at the Yoni, and their story ends there. They also talk about where the migrant brothers, the friends, the neighbors passed by when they left: if they went by Colombia if they crossed the sea if they arrived in Guatemala, El Salvador or Mexico. With these stories of migrants, as a child, one learns of geography, of the route to the north. Also, from a very young age, one knows that the coyotes are the ones who take the people. But nothing else. When you are a kid, you develop a personal idea of the road, without knowing everything that goes on. Then, as an adult, one finds out the rest.

Indeed, the stories about immigration passed down from generation to generation determine the construction of an individual and collective geographic imagination about the route Ecuador-Central America-Mexico-the United States, and about the role the coyotes but also the chulqueros (moneylenders) play. Indeed, the children and adolescents from the Austro grow amidst stories of crossings, of debt, of loans, of departures, of calls from far away, of news from the north, of coyotes, of migrants. Thus, from a tender age, as Aída well says, they imagine the road, while the dynamics of irregular immigration becomes part of their daily life. Though the geography of the route is known, the different types of violence that inundate it becomes an open secret that will reveal itself later.

Aída is very assertive when she says that, “when one is a kid, one develops a personal idea of the road (…) Then, as an adult, one finds out the rest.” Undoubtedly, comprehending the various types of violence on the road changes form, revealing its complexity, insofar as the ones who stay grow up and their image of the route fills with stories of other kinds.

When my brothers left, they called my mother and said to her: “Mommy, I’m here.” My mommy would ask: “How was it?” And they only said: “Good.” My brothers never told her what actually happened. They never said, “the route is horrible,” “I almost died in the desert,” “there wasn’t any water to be had.” No, they don’t say that. They only talk about good things. A fantastic idea of the route is thus created. Like a myth that everything is alright on the route, but it’s not so. Only after, much later, they recount their stories.

The myth of the route, as Aida says, facilitates the collective construction of an imagined route where, although dangers are known to exist, what matters is travelling the route to arrive at the destination. The objective is to cross Mexico’s northern border to begin a new life in the Yoni and the rest of the story remains temporarily muted. Many caregivers and also immigrants who have returned or have been deported and live in the Austro say that it is in the United States, after Ecuadorian immigrants have arrived and trust other immigrants, when they recount their stories about the route and compare experiences. Migrants don’t share stories about the various contrasting types of violence in Ecuador, but they do in their destination: the United States.

“They talk to each other over there (in the United States), not here (in Ecuador),” says the vastly experienced Aída. And goes on:

Only those who have reached there can compare their route with others, but over there (in the United States). Not here (in Ecuador). Only there do they start remembering. When they speak about the route, but only there [in the U.S.], with others who can speak their language, the language of those who have left by the road and have had that experience and keep it with them. They don’t talk to everybody, much less to those who have not made the journey.

Precisely for this reason, children and adolescents grow up with the idea of an imagined route, where there aren’t always the different types of violence or only certain vague notions of the kinds of violence along route Ecuador-Central America-Mexico-the United States. For this very reason, the desire to leave persists and nurtures itself. Later that image of the route will mutate and take on other nuances, undoubtedly very complex.

CUIDADORAS EN NÚMEROS

NIÑOS AFECTADOS POR EL FENÓMENO

%

de la población vive fuera del país

%

MIGRANTES DEJAN A SUS HIJOS ENCARGADOS

¿Por qué es relevante?

Las cuidadoras no sólo están en el Austro, están en muchas otras localidades de Ecuador, y también de Colombia, Brasil, El Salvador, Guatemala, México e incluso Estados Unidos. Ellas cuidan con especial cariño a los miles de niños y niñas que tienen a sus padres viviendo fuera del Ecuador; estas mujeres son el sostén de sus familias, nos cuidan cuando estamos enfermos, cuando estamos desvalidos y cuando más necesitamos el calor de un hogar; son las protectoras de nuestras memorias.

Además ellas son las que guardan los relatos del viaje, del dolor de éste. Piensan en los que ya no están, los rememoran y en cada relato los traen al presente. Acumulan historias, que son las de sus familias y las memorias de la emigración ecuatoriana. Son claves en nuestro relato porque son las veladoras de un país desmemoriado….

Cuál es la situación

“La tierra se queda huérfana”, así lo nombran las cuidadoras para referirse a la emigración que ha tenido lugar en Ecuador. Son al menos 2 generaciones familiares de mujeres y hombres quen han emigrado a Estados Unidos de manera incesante, desde por lo menos finales de la década de 1960.

“También se quedan huérfanas las abuelas”, miles son las mujeres mayores se quedan solas en la vejez, cuando necesitan los cuidados de quienes ellas algunas vez cuidaron.

cómo puedes apoyar

Las historias que nos comparten las cuidadoras guardan las memorias de la emigración ecuatoriana. Ellas no olvidan de que la pobreza detonó la salida de sus seres amados. Tampoco han olvidado cómo fue la partida de cada uno de sus hijos e hijas, o de sus esposos, o de sus hermanos.

Sus historias nos convocando a crear mundos más justos. Conéctate con aquellas personas que están construyendo espacios seguros para ellas.

Footnotes

- Passing “by the pampa”, “by the chacra” and “by the road” are local expressions used to name irregular migration from Ecuador to the United States.

- International Organization of Migration, IOM, World Migration Report 2013. Migrant Wellbeing and Development, Geneva, IOM, 2013.

- National Institute for Statistics and the Census, Reporte de pobreza y desigualdad, Ecuador, 2018, https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/POBREZA/2018/Junio-2018/Informe_pobreza_y_desigualdad-junio_2018.pdf.

- Ídem.

- Luis Noe-Bustamante, Antonio Flores y Sono Shah, “Facts on Hispanics of Ecuadorian origin in the United States, 2017”, Pew Research Center, Hispanic Trends (website), https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/fact-sheet/u-s-hispanics-facts-on-ecuadorian-origin-latinos/

- Observatory for the Rights of Children and Adolescents of Ecuador, ODNA, Los niños y niñas del Ecuador a inicios del siglo XXI. Una aproximación a partir de la primera encuesta nacional de la niñez y adolescencia de la sociedad civil, Quito, Observatory for the Rights of Children and Adolescents, 2010.

Bibliographic references

This text arises from a multi-sited ethnography developed in the Azuay Province, Ecuador, between January and September 2019. The places where ethnographic immersion took place were Cuenca, Gualaceo, Cochapamba, Jima, La Moya, Girón, and Guachapala. Most testimonies were collected in September 2019. In-depth interviews were conducted with 12 caregivers and 14 sons and daughters of migrants, reconstructing their biographical path and emphasizing the migrant experience in their lives. This piece draws upon two previous pieces of research.

Firstly, the work draws on an exploratory ethnography that began in 2016 during the first immersion in the field for my doctoral research, where I analyzed the historical and contemporary production of Ecuador as a global space of migratory transit: Soledad Álvarez Velasco, “Trespassing the visible. The production of Ecuador as a global space of transit for irregularized migrants moving towards the Mexico-US corridor”, Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor, London, Department of Geography, King’s College London, 2019. Secondly, this piece draws on the research included in the book Soledad Álvarez Velasco and Sandra Guillot Cuéllar, Entre la violencia y la invisibilidad. Un análisis de la situación de los niños, niñas y adolescentes ecuatorianos no acompañados en el proceso de migración hacia Estados Unidos, Quito, SENAMI, 2012.