Diversity, Violence, Poverty

Lives in Search of Help

The migration of Central American children and adolescents forced to flee their countries to the United States has been ongoing for more than twenty years. It was not until July 2014, however, when international news agencies, particularly from the United States, raised the alarm after the U.S. immigration system entered into a crisis as a result of the arrival of thousands of underage migrants into the country. Barack Obama, then the U.S. president, declared it a “humanitarian crisis.” Between 2014 and 2019, despite some variations, the statistics continue to be alarming. The phenomenon remains a reality impossible to ignore.

Many migrant children stay in government-run shelters at some point during their journey through Mexico. Still, they increasingly find refuge in shelters run by religious and civil society organizations that have increased their services due to the arrival of tens of thousands of foreigners entering the country irregularly. Notable among these “Migrant Homes,” as they are also called, is Hermanos en el Camino [Brothers along the Road], a network of shelters on the southern border and in central Mexico created in 2007 by Alejandro Solalinde, a priest and human rights advocate.

Migrant children and adolescents of different nationalities and ethnic groups transit through these welcome and support centers. Most are mestizos from Central America and originally from rural communities, like Fernando, a 12-year-old Salvadoran boy. Typically, there are also indigenous Mayan children from Guatemala, like Elder, 10, who belongs to the Mam ethnic group, and other Mayans from the Kaqchikel and K’iche’ peoples. There are children of African descent, such as Wilmer, 12, from the Garifuna people in Honduras, and other Honduran migrants from the Lenca and Tawahka indigenous groups, some of whom are proficient in English and French in addition to Spanish. Other youngsters are like Pedro, 16, from the Miskito people, an ethnic group of Afro-Caribbean descent, that make the journey from Nicaragua.

Diversity among these young migrants is also evidenced by the kinds of displacements they experience. While some migrate with their families, others are “separated” from their loved ones or are “unaccompanied,” to use the legal terms. The latter find themselves in the most vulnerable situation while facing the challenges of the journey. Such is the case of Antonio, 14, a Guatemalan who left home because of the extreme poverty afflicting his family, and he was driven to quit school and seek work beyond the border to help the mother and siblings he left behind.

The reasons that young children and adolescents migrate alone or accompanied are usually interrelated. Victoria, for instance, is a Salvadoran girl who fled El Salvador to escape domestic violence, reunite with her father in the U.S., and elude the harassment of the Mara gangs that were pressuring her and her sister to join the MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha). “Whenever they would see us in the street, they cornered us. They somehow managed to get my mom’s phone number and began sending her messages and calling her, threatening her; they would also leave written messages under the door… we felt terrified, and we came because of that too.” Victoria tells her story in the following way:

I took care of my little brothers from the age of 7. For this reason, I wanted to have children of my own, because I knew how to care for them well, so to say. My first baby was born when I was 13 and my second child now when I’m 15 but from different fathers. In my country, I had to work taking care of children and as a maid. I had to drop out of school when I got pregnant the first time. I was not very good at school and got as far as the sixth grade. I don’t know how to do much; it’s why I must clean houses.

Upon arriving at Ixtepec City, Oaxaca, Victoria, her mother, and her two sisters went to the Hermanos en el Camino shelter, where they allowed us to stay. There, they could eat, shower, rest, receive legal advice, spiritual support, medical first aid, and psychological help. “My knees were in bad shape when I got there, they hurt a lot because of all the walking and spending so many hours in the same position. I saw a doctor at the shelter: she gave me a pill and ointment for my knees and bandages to wrap them in.”

Doña Consuelo, the girls’ mother, participated in an informative talk offered by Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission at the shelter. In the discussion, she learned that she could regularize her immigration status in Mexico. She would be able to stay and work for at least a year, save money, and help her husband with expenses for the journey to the U.S. So she initiated the regularization process at National Institute for Migration. But since the process is much slower in Ixtepec, Consuelo decided to continue her journey to the Mexican capital.

Her goal was to arrive at another Hermanos en el Camino shelter in Mexico City. While they managed to get there, the journey was full of dangers and setbacks. “We were robbed on the train. The police asked for money every time we encountered them; other thieves also took our cellphones and clothes when we had no more money to give. For this reason, it took us over a month to reach Mexico City; because we had to stop so my mother could get a job or to wait for my father to send us money.”

The dangers of migrant transit through Mexico impact everyone, regardless of physical condition, gender, or age. But children and adolescents are more likely to become victims; their physical and psychological development as minors makes them more defenseless. Some of the most cited dangers include illness, accidents, sexual violations, thefts, trafficking in persons, forced induction into criminal networks, labor and sexual exploitation, xenophobia, physical and verbal abuse, discrimination, extortion, and human rights violations. Organ trafficking also exists, but it is difficult to access data sources and track precise figures as it is controlled by more organized and dangerous criminal networks.

Another reality confronting Central American adolescents is that many are already parents, which makes their needs and life circumstances distinct. It is common in Central America for children and adolescents to take on adult roles and responsibilities at a young age. Many girls, for instance, are left to care for their younger siblings and see their childhood abruptly cut short as they undertake responsibilities beyond their years. This often leads to early marriage or pregnancy, as it happened to Yoselín, a 15-year-old Honduran girl from the Atlántida Department in Honduras.

Our journey was challenging because we didn’t know anything. It was also very tiring as we had to walk a lot, too much. We took many buses. First to a town in Guatemala, then another to the capital, and then another to the Mexican border. From there, in Tecún Umán, we paid for a raft to take us across a river, and then we walked and walked like three days, sleeping in the mountains, eating cookies, and drinking juices. Then we got on a train, and this was the most horrible part because there was no room inside. Some men gave us their spots between two train cars, and we had to stand for more than twelve hours. There were only a few small crossbars to stand on, and it was horrible seeing the train wheels underneath. We had to take care of each other ourselves, to make sure neither of us fell asleep, and on it went, until we finally arrived at Ixtepec.

Victoria, salvadoreña, 12 años.

Yoselín and her second child’s father fled Honduras with both children to escape poverty, the lack of opportunities, and the growing social instability that started towards the end of 2017 after U.S.-backed Juan Orlando Hernández was declared the winner of the presidential election. The event triggered the organization of migrant group caravans in San Pedro Sula wanting to escape unrest and looking northward for better living conditions. While this Honduran family did not migrate as part of a caravan, they did abandon their country for the same reasons and arrived in Mexico, relying on “rides” and long walks.

Today, Yoselín, her husband, and her children wait for their asylum application in Mexico to be approved. In the meantime, they live in the shelter. He works as a mason’s assistant, and she works as hired help in a grocery store

Pregnancies in adolescents under the age of 15 increase because of factors like inadequate information, lack of sexual education and access to health care, and male-dominated culture, among others. Based on what we know from the shelters, it’s substantiated that Central American mothers often have their first child when still only girls and their parents and families often abandon them. Among other causes, this is due to immaturity or fear of taking on additional responsibilities, especially considering the fathers are adolescents themselves. Further, the patriarchal and male chauvinistic system prone to violence against women can also play a role. Therefore, it is common for a woman to have children with different fathers.

“Here at the DIF [National System for Integral Family Development], we have delivered several babies to adolescent mothers. I do not think that this is right for those who are still girls to become mothers themselves. Therefore, later, they don’t pay attention to their children, carrying them around carelessly like little animals, dirty and malnourished” (nurse at a transit shelter of DIF Oaxaca, February 7 of 2019). Remarks like these are common among civil servants or society members prone to stigmatizing early motherhood, who do not have an in-depth understanding of the social causes that give rise to it.

Additionally, it is common for young fathers to quit school since males prefer to find a job that helps them meet their new responsibilities, while underage mothers choose to care for their babies. If the mothers are single, most need to find a source of income, which generally involves domestic work or the informal trade, be in their places of origin, or during migration.

Many of these children and adolescent boys and girls are often forced or convinced to join gangs and organized crime groups. Far from deserving sanctions or punitive treatment, they desperately need institutional support to develop scenarios and networks that distance them from possible risky behaviors. This was the case for Josué, 13, of the Guatemalan Kaqchikel people who, abandoned by his parents, believed he could find a family in the Barrio 18 street gang. Weary of the increasing violence he was forced to carry out, he attempted to leave the gang, but it was not permitted, so it drove him to emigrate, to safeguard his physical well-being.

The common denominator among these children and adolescents is that they come from broken families. Migrating for them is not a choice but rather something they are forced to do, and for many, like Josué, it becomes a survival strategy. But for all of them, the journey is riddled with danger, human rights violations, and inadequate immigration policies that do not offer them protection or the life alternatives they require.

It is also worth remembering that the now generations-long violence in countries like Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador has permeated their social values, becoming a cultural practice as well, normalized at home and in the public realm. For these reasons, the lives of minors are filled with different types of violence: structural, social, domestic, or family, and sexual and psychological, among others; it is not surprising that many find migration as a way to escape violence.

Listen: A Long Journey

Mynor

The Road to a New Life

mynor

Mynor,16, is an adolescent from Tegucigalpa, Honduras. His father abandoned him and violence was usual among his paternal figures. When passing through Mexico, the “Hermanos en el Camino” shelter supported him. There, he was aided in filling out his refuge claim and received psychological counseling. Mynor wishes to settle in Mexico and dreams of having a safe space to live and start a new life.

Mynor, 16, is an adolescent from Tegucigalpa, Honduras. His father abandoned him. His male role models were a few uncles and cousins who had joined the Barrio 18 street gang, so violence was always present in his family environment. The physical violence, use of weapons, alcohol, and drug consumption that he witnessed from an early age fostered his curiosity to try drugs at 10, which led him to join the local gang eventually. This is understandable considering that minors lacking the support of adults during their formative years, to instill values, care for and show them affection, may try to fill the gaps with street gangs like the Maras. The gangs become substitutes and replacements for the family, effective control devices that instill the criminal organizations’ norms and values. They provide both children and adolescents a sense of belonging to a group that shares common interests, tastes, its own spoken language and body language, and even similar emotions.

Children and adolescents are drawn to the affection and sense of security, the promise of vengeance, pleasure, and power that gangs offer. If they successfully fulfill the “assignments” entrusted to them, they could get a better rank and leadership within the group. Many believe the gang is the solution to all their problems. Even if they are not actively involved with the Maras, they may sympathize with a specific gang and sustain friendships with its members. In Mynor’s case, he affirms: “A cousin got me in the gang, and I started selling drugs at the school. After school, he would come to pick up the money from what I sold and try to recruit more cipotas and cipotes (girls and boys) like me.”

As confirmed by Mynor’s account, instead of the safe spaces they should be, many schools in the region have become high threat environments that similarly contribute to school dropouts. “They come here with deficient educational levels and many display violent, aggressive attitudes, so it’s not easy to convince district supervisors or parents of other children to accept them in our school. Truth be told, we are afraid of them.” (Director of an elementary school in Ixtepec, March 27, 2018).

This prejudice, unfortunately, does not help to improve the vulnerability scenarios that the children bring with them from their communities. Instead, they reproduce the stereotypes that associate them with gangsterism and crime. Mara leaders take advantage of the lack of socio-educational measures and social alternatives, among other factors, to recruit ever-younger children. The problem is made worse by the fact that many vulnerable children and adolescents paradoxically believe that joining a gang guarantees their personal safety. Over time, however, they realize that the group can be ruthless if you don’t follow the rules to the letter; namely, if you disobey an order, contradict a superior or if misunderstandings and frictions between members are allowed to develop. When infractions occur, instead of finding protection, members risk becoming victims of violence, as it happened to Mynor.

I had already done the brinco , and for a while, everything was alright with the brothers. But then I got me a beautiful girlfriend, and one of the bosses decided that he wanted her for himself. He threatened me when I wouldn’t go along, but I didn’t think he would do something. Then one day, my girlfriend turned up dead in a vacant lot near her house. Right there, I realized that I was next, so my only choice was to make a getaway. While still there, in Chiapas, between La Arrocera and Huixtla, I saw I was being followed. The same thing happened in another municipality here on the isthmus, but I can’t recall its name—the thing is I don’t know the area around here […] I wonder who gets tired first; me of hiding or them of following me. We’ll see what happens.

After walking for a long time and getting on the train known as La Bestia [The Beast], Mynor reached Ixtepec. He followed another migrant group already familiar with the shelter. There he was informed of his rights as a migrant, a minor, and as a victim of violence. Given the risk to his life, he was entitled to international protection, and Hermanos en el Camino staff helped him with the asylum. “Here, they made me see the bad things I had done. But before anything, they told me I could change. I don’t want to keep doing what I did in my country. I want to study, work, and be a good person, more so now that I’m a Christian.”

While it is true that, given their personal stories, some Central American minors become involved in harmful or criminal behavior, it is also true that the vast majority do not get involved in illegal activities or consume drugs because they are running away from the Maras and other gangs precisely to get away from those scenes of violence. Some want to resume their studies while others prefer to work, save money, and continue their journey to the U.S. Others want to send for their family members or use job earnings to send remittances to their relatives. Some, like Mynor, wish to settle in Mexico, rent a living space, and start a new life with a clean slate.

SHELTERS

Religion and Reception and Refuge Places

Hermanos en el Camino

This shelter supports migrants on their way and defends them in the fight for the recognition of their human rights.

Phone numbers: 722 216 1469 y 722 503 0879.

Founder and Coordinator: Armando Vilchis Vargas

metepec, Estado de México

CAFEMÍN

The ecclesiastical organization advocates for human rights and is run by the Congregation of Josephine Sisters since 2012.

Phone number: 55 5759 4257

Director: Sister Magda.

CIUDAD DE MÉXICO

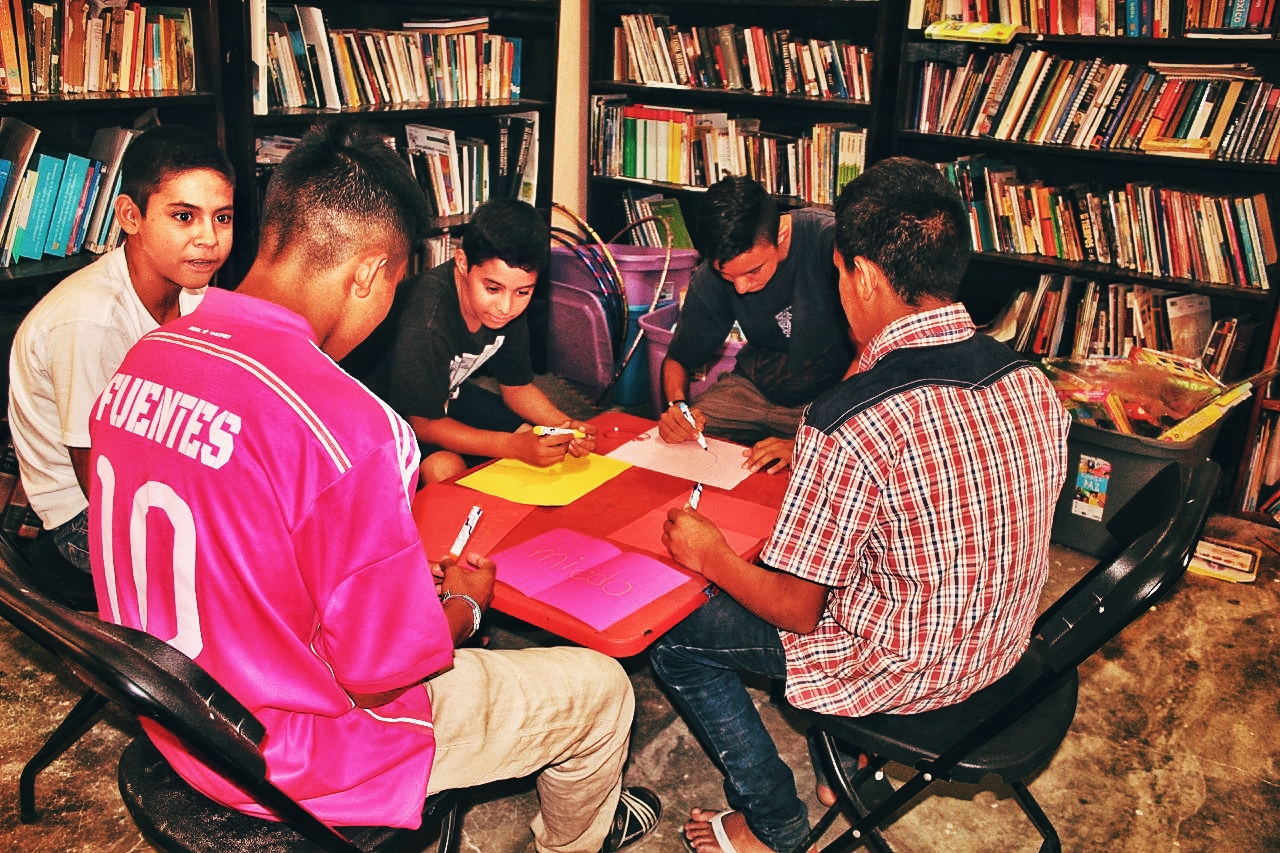

Because of the services they provide, shelters constitute a protective element for underage migrant children and adolescents. While limited, these services contribute to countering the harmful effects of irregular migration. “You could say they are an oasis along the way […] they are places of respite and protection for the weary, the ill, the hurt, and the damaged.” Besides covering basic needs, shelters also offer information and legal advice on migration processes. Many organize recreational activities and workshops focused on themes like health and human rights, among others.

Only a few shelters like Hermanos en el Camino offer the medical and psychological help that is so necessary for this vulnerable sector of the population. Shelters willing to accept unaccompanied children and adolescents, as does this one, are unfortunately scarce. Hermanos en el Camino also offers personalized support and accompanies these minors through the immigration regularization process. While nearly all transit shelters only allow for a maximum stay of three days, this network of shelters permits migrants to stay for the duration of their regularization processes—especially unaccompanied children and adolescents—whether they are applying for a humanitarian visa or seeking refugee status, a process that may take from one to six months.

All these minors intend to reach the United States. However, when they realize how difficult it is, many opt to remain in Mexico and try to regularize their residency there. Others are less likely to be deterred from their original goal, taking advantage of the immigration processes or permits to advance northward through Mexican territory without fear of being detained and deported. Whether the goal is to reach the United States or to settle in Mexico and build a new life there, for each child and adolescent, the National Institute for Migration and the Mexican Commission for Refugee Aid have different meanings and utility. Migrants use and adapt the services provided by this institution according to needs, which underscores the ability of individuals to act and make decisions under these kinds of circumstances.

Shelters also perform a crucial role in the migration process, as the information and legal advice they provide allows minors to strengthen their capacity for action. The same is true of psychological and spiritual support. Where children or adolescents have been victims of a crime, the presence of caring professionals or volunteers can help them feel supported and develops their capacity for resilience by strengthening their self-esteem, confidence, ability to adjust, their tolerance, or their enthusiasm to rebuild after confronting complex experiences.

What Do Children Think about Shelters?

When it is needed

You don’t know if you can become a migrant overnight, and what you will need

When you need help

Here they cured my feet and knees when I arrived with big sores and blisters. Then they helped me get into a hospital when I had appendicitis.

When you don't have a home

Migrants who don’t have a house in other countries can go to shelters and stay there for a while. Also, shelters protect migrants. They see that nothing bad happens to them, and all that.

When you need information

Thanks to the information I received in a shelter, I could defend myself and avoid being sent back to my country, when migration police caught me in Veracruz. A place to be. That’s why it’s good there are places like shelters.

When you need to have safety

If there were no shelters, who knows what would happen to so many migrants— they would have to sleep in the street’s shelters. And if it rains… Just imagine! Everybody would be sick. In contrast, in a shelter, they’re under a roof and safe, nothing can happen to them.

Many children do not have a clear idea of what a country is until necessity forces them to cross borders. Once they leave the boundaries of their nations behind, they realize how different reality can be. It is until then when they comprehend the meaning of the words “migrant,” “alien,” and “undocumented,” when they experience discrimination or xenophobia for the first time. Therefore, many resort to mimicking forms of speech or dress or behave like Mexicans, to pass as a national and not be identified as “the other.” In other words, they adopt new identities to adapt as needed within specific contexts.

Therefore, they often have fun in the shelters learning Mexican words and idioms with the volunteers. But beyond playing games, understanding the codes of conduct and language of the country they transit through helps them prepare for possible future questions from police or immigration agents if detained, and thus avoid deportation.

In addition to organizing games and workshops, another benefit offered by Hermanos en el Camino is spiritual support, regardless of the religion that each one professes. Occasionally, the shelter director or another priest officiates mass. Data shows that most Central American migrants are evangelical Christians, in its various denominations. However, no matter the religious belief system practiced by each boy, girl, or adolescent, faith forms the central pillar in their lives according to their testimonies. In times of danger, doubt, adversity, or hopelessness, faith helps them overcome negative episodes. It is common for Catholic migrants to take images of saints and scapulars in their belongings for their journey, while evangelicals carry the bible with them. In this way, the faith of children and adolescents is also trans-nationalized, given their need to have spiritual references along their migration route.

You should always carry your bible, you know? Because that way, God, our Lord, is with you to protect you. My dad reads it to my brother and me at night before bed. He says it is essential for us to know ‘the word”. My little brother and I like the praises, singing in the choir at my church. I can’t tell you how much I miss that!

David, 10, Honduran.

God is everywhere. Everything exists because of him, including us. He makes sure nothing bad happens to us. That’s why the last time they mugged us, the thief did not slash my uncle with a machete, as he did to another man—nearly severing an arm—for having no money or anything else to steal. They just left us there stark naked, took our backpacks, cell phones; they even stole our sneakers! Thank God they didn’t hurt us. Go figure! What’s the point!

Daniel, 8, Salvadoran

Comfort is not the only thing these youth find in religion. Temples or churches are also spaces for socializing and feeling safe, free from prejudices or stigma. They can also develop support networks that help assimilate or be referred to various services—education, employment, health, housing, and leisure.

First, a priest came to the shelter, and I liked what I heard him talk about. Afterward, he took me aside and asked if I wanted to visit his church. I went there, and because I liked it, I kept going. Then a lady offered me a job, and I’m working with her, learning how to make bread.

Mynor, hondureño, 16 años.

WHERE TO?

An Uncertain Outlook

History and the testimonies show an increase in violence through the entire region resulting from several factors. Notably, the ongoing economic crises, natural disasters, the strengthening of the Maras, paramilitary groups, and organized crime. As a result, entire communities, including children and adolescents, are displaced from the territory in increasingly significant numbers. In the absence of adequate living conditions, Central Americans are generally helpless in terms of job opportunities and medical, social, educational, and cultural stability. This drives them to seek opportunities and security they cannot find in their own countries elsewhere.

As a result of the risks and violence present in the Mexico-United States immigration corridor, it is common that minors are victimized more often than adults. And if we add to this the increasingly adverse conditions in their places of origin (malnutrition, low educational levels, early pregnancies and paternity, among others), their vulnerability deepens. Many adolescent pregnancies, for instance, result from sexual abuse. These pregnancies can lead to self-esteem issues in mothers-to-be and to the inability to control emotions and behaviors—which sometimes translates in affective indifference or maternal negligence, thus increasing the adolescents’ needs for psychological, medical, and nutritional support.

Likewise, when children and adolescents quit school to emigrate, it becomes challenging to resume their education while in transit, because conditions are unsuitable in Mexico or the peculiarities of each migratory status prevent them from settling in one place.

Conversely, increasing violence by the Maras and other gangs in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras produces one of the highest murder rates in the world. Generalized social perception nonetheless blames children and adolescents for this greater violence and insecurity. Because many do not choose to join but are recruited by force, one cannot judge their involvement through conventional parameters. Harsher punishments and lowering the minimum age for criminal liability are announced instead of considering measures based on a restorative justice model.

Control and repression of minors in trouble with the law “must take a back seat to child protection and guarantee the restitution of their rights.” Also, their rehabilitation and social reintegration aided by psychological therapies, treatments for addiction, educational training, sport, and recreational activities, among others. We should not lose sight of the age of those involved and their level of emotional maturity nor the various factors relevant to their circumstances: ethnic origin, age, gender, sexual preference, cultural contexts, and life paths, to mention just a few. Social programs and public policies designed to care for migrant children and adolescents must take all of this into account because they are diverse, not a homogeneous group with different needs. Some require a high degree of international protection, while others only need assistance to reunite with their parents or relatives in the U.S., some need help assimilating into Mexican society as their chosen destination through access to education, health, or work.

Given the legal loopholes and dangers threatening migrant children and adolescents, humanitarian shelters are thus of vital importance. They assume functions that correspond to the State. Facing the negligence of the State, religious communities, and civil society step forward, offering migrants, among them minors, safe havens during their journey. In addition to satisfying basic needs, shelters offer migrants information, workshops, legal advice, and emotional guidance, which allows them to maximize their ability to act, make decisions, and develop more resilient personalities.

MIGRANT SHELTERS IN MEXICO

SHELTERS

Migrants

Volunteers

Why Is it Important?

The migration of children and adolescents forced to leave their countries in Central America to reach the United States was declared a “humanitarian crisis” between 2014 and 2019.

At some point during their journey through Mexico, migrant children need government shelters or shelters managed by religious communities and civil society organizations. Official shelters do not accept children because of the various legal and logistical challenges caused by the great diversity in origin and travel conditions faced by thousands of migrant children. Some are with their families, others are unaccompanied.

Religious communities and civil society have created these spaces as a haven for children and adolescents who otherwise would not have safe places during their journey. These organizations carry out tasks that allow migrants—including minors—to have secure areas during their trip.

A PICTURE OF THE SITUATION

There are around 96 shelters, canteens, and migrant houses across the different regions in the country (North, South, Gulf, Pacific, West, etc.) because of the many different routes migrants follow in Mexico. Every year thousands of minors need the help these places offer. However, only a few shelters take in children and adolescents, especially if they are traveling alone.

How to Get Involved

In shelters created thanks to religious institutions and civil society organizations, migrant children and adolescents can meet their basic needs, and get information, legal counseling, and emotional support. Support for these spaces is vital, especially given the inaction of governments.

Listen carefully to the voices of these boys and girls that push us to create a more just world. Connect with the people who are building these safe spaces for young people in shelters.

Notes

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection, “United States Border Patrol Southwest Family Unit Subject and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions Fiscal Year 2016”, Estados Unidos, US Department of Homeland Security. Recuperado el 4 de noviembre de 2016 de http://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-border-unaccompanied-children/fy-2016#

- Se cambiaron los nombres de las niñas, niños y adolescentes para proteger su identidad.

- El Comité de Derechos del Niño llama así a los que han tenido que renunciar a sus padres biológicos pero viajan con parientes o adultos integrantes de su familia extensa. Naciones Unidas, “Trato de los menores no acompañados y separados de sus familias fuera de su país de origen”, Observación General 6, Comité de Derechos del Niño, CRC/GC/2005/6, 2005, párrafos 7 y 8.

- Se define como “no acompañados” a aquellas niñas, niños y adolescentes que se encuentran fuera de su país de origen y viajan sin la compañía de padres o tutores, y que por ser menores mayores de edad no pueden ejercer sus derechos civiles y políticos. Idem.

- De acuerdo con UNICEF y la CEPAL, en estos tres países, principales expulsores de migrantes de América Central, los índices de marginación son muy elevados, sobre todo en las zonas rurales, por lo que la cobertura y la calidad de los servicios son muy limitadas. La pobreza o pobreza extrema en que viven muchas de las familias de la región les impide contar con los recursos suficientes para satisfacer las necesidades básicas, entre ellas, la alimentación, lo que a su vez propicia elevados niveles de desnutrición infantil, otra más de las violencias sistémicas que afectan a los más vulnerables. “La pobreza de América Latina y el Caribe aún tiene nombre de infancia”, documento preparado para la XI Conferencia de Esposas de Jefes de Estado y de Gobierno de las Américas, México, 25-27 de septiembre, 2002. Recuperado el 9 de enero de 2017 de https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/1565-la-pobreza-america-latina-caribe-aun-tiene-nombre-infancia

- Se conoce como “brinco” al rito de iniciación para hacerse miembro de la pandilla, el cual consiste en recibir, durante cierto número de segundos, golpes indiscriminados por parte de los demás integrantes del grupo; aunque en la actualidad, de acuerdo con diversos testimonios, algunas pandillas han modificado este requisito y, en su lugar, exigen al novato cometer ciertos delitos.

- Los desafíos de la migración y los albergues como oasis. Encuesta nacional de personas migrantes en tránsito por México, México, CNDH-UNAM-IIJ, 2017, p. 18.

- Una situación habitual: La violencia en las vidas de niños y adolescentes, Nueva York, UNICEF, 2017, pp. 5-8; “La caravana a su paso por Chiapas”, Save the Children, 21 de octubre de 2018. Recuperado el lunes 22 de octubre de 2018 de https://www.savethechildren.mx/enterate/noticias/la-caravana-a-su-paso-por-chiapas

- Merino García, Keila, Maras en Centroamérica y México, Madrid, Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado, 2018, p. 11.

References

Comisión Económica para América Latina, CEPAL, y Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia, UNICEF, “La pobreza de América Latina y el Caribe aún tiene nombre de infancia”, documento preparado para la XI Conferencia de Esposas de Jefes de Estado y de Gobierno de las Américas, México, 25-27 de septiembre, 2002. Recuperado el 9 de enero de 2017 de https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/1565-la-pobreza-america-latina-caribe-aun-tiene-nombre-infancia

“La caravana a su paso por Chiapas”, Save the Children, 21 de octubre de 2018. Recuperado el lunes 22 de octubre de 2018 de https://www.savethechildren.mx/enterate/noticias/la-caravana-a-su-paso-por-chiapas

Los desafíos de la migración y los albergues como oasis. Encuesta nacional de personas migrantes en tránsito por México, México, CNDH-UNAM-IIJ, 2017.

Merino García, Keila, Maras en Centroamérica y México, Madrid, Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado, 2018.

Naciones Unidas, “Trato de los menores no acompañados y separados de sus familias fuera de su país de origen”, Observación General 6, Comité de Derechos del Niño, CRC/GC/2005/6, 2005.

Una situación habitual: La violencia en las vidas de niños y adolescentes, Nueva York, UNICEF, 2017.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, “United States Border Patrol Southwest Family Unit Subject and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions Fiscal Year 2016”, Estados Unidos, US Department of Homeland Security. Recuperado el 4 de noviembre de 2016 de http://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-border-unaccompanied-children/fy-2016#

INEGI. (2015). Censo de Alojamientos de Asistencia Social (CAAS) Presentación de Resultados. Recuperado de https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/caas/2015/doc/caas_resultados.pdf

BBVA. (2020). Mapa 2020 de casas del migrante, albergues y comedores para migrantes en México. Recuperado de https://www.bbvaresearch.com/publicaciones/mapa-2020-de-casas-del-migrante-albergues-y-comedores-para-migrantes-en-mexico/