The Origins of the Movement

Migrant Caravans

The forced migration of Central American people to the United States has been a constant for more than three decades. However, before October 2018, migration was made up of small groups or families that traveled alone, joining other groups of migrants from the southern Mexican border to accompany and protect each other. Though the percentage of people was high, it did not scare Mexican or U.S. society or their respective governments. In contrast, the recent so-called “Caravans” did scare society because they involved thousands of people who, by traveling together, not only attracted media attention but also caused a crisis in border health and humanitarian aid systems.

The origin of the first Caravan of this period goes back to the Holy Week processions. A Franciscan priest, founder, and coordinator of “La 72” migrant shelter, in Tenosique, Tabasco, Mexico, began organizing this procession when he founded the shelter in 2011 to represent the Stations of the Cross. The representation of the Stations of the Cross mainly involved migrants staying in the shelter, so the priest equated the suffering they faced during their migrant journey with Jesus’ pain before the crucifixion. In 2014, more migrant shelters joined this procession. Among others: “Hermanos en el Camino“; for this reason, Brother Tomás, the then director of “La 72”, and several religious leaders decided to transform this Catholic act into an “act of civil disobedience” to shed light on the dangers, abuse, and human rights violations suffered by Central American persons.

Thus, the then called “Migrant Stations of the Cross” moved through several states in Mexico, until it was joined by more than a thousand people, transforming into a Caravan, and secured a permit from the Mexican Ministry of Interior, through the intervention of the National Institute for Migration. The institute issued an “Oficio de Salida” or exit permit. In this way, the members avoided deportation or becoming victims of violence since they were authorized to remain 30 days in the country. In addition, the government provided buses that helped them cover great distances and approach the northern border. For this reason, many managed to reach the United States. This situation motivated other Central American persons to repeat the political action during Holy Week in the following years.

In 2018, the founder and Director of the “Pueblo Sin Fronteras,” shelter located in Caborca, Sonora, headed a group, mainly of Hondurans, in an attempt to bring them to the border with the United States, and use international media to convince President Donald Trump to grant them asylum in the U.S.. However, many of the migrant shelters in Mexico distanced themselves from this leader’s actions. Nonetheless, he negotiated with Mexican authorities to be granted “Oficios de Salida” for approximately 300 people, among them women, children, and adolescents, who entered the United States to seek asylum.

Meanwhile in Central America, the economic, political, and social conditions continued deteriorating while violence surged. This situation led to the formation of an ever before seen Caravan in Honduras in October 2018. More than 7000 people from Central America arrived together in Mexico, intending to reach the United States. According to data produced by the Suchiate Municipality, more than 2 000 were children and adolescents. While they entered Mexican territory from Honduras and El Salvador, other exoduses also organized their departure.

The U.S. government response was swift. The Department of Homeland Security implemented a “zero-tolerance” policy, separating families at the border to discourage immigration. More than 2300 girls, boys, and adolescents that were with their parents or other relatives were sent to detention centers adapted as shelters where minors were kept in “cages” and subjected to physical and psychological abuse. As of June 2019, six children had died in these shelters. The deaths were never cleared up nor were the responsible parties punished:

- Darlyn Cristabel Córdova Valle, Salvadoran, 10. Died from cardiac complications on September 29, 2018, in the custody of Texas Border Patrol agents.

- Jakelin Caal Maquin, Guatemalan, 7. Died of septic shock on December 8, 2018, in the custody of New Mexico Border Patrol agents.

- Felipe Alónzo Gómez, Guatemalan, 8. Died of a bacterial infection on December 24, 2018, in the custody of U.S. border agents in New Mexico.

- Juan de León Gutiérrez, Guatemalan, 16. Died of a cerebral infection on April 30, 2019, in a U.S. Government shelter in Texas.

- Wilmer Josué Ramírez Vásquez, Guatemalan, 2. Died of pneumonia on May 14, 2019, in Texas, after being detained with his mother.

- Carlos Gregorio Hernández Vásquez, Guatemalan, 16. Died on May 20, 2019, a day after the U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported that the adolescent had been diagnosed with the flu. The death certificate determined his death occurred by “unknown causes” when he was transferred to the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services. However, there is a video showing that the minor died in the care of the Border Patrol because he did not get prompt medical attention.

Other cases were presented.

Like that of Valeria Martínez, Salvadoran, 23-month-old, who drowned on June 23, 2019, with her father, Óscar, a 25-year-old young man in the river that divides the states of Tamaulipas, Mexico, and Texas, U.S. Or the case of Gurupreet Kaur, from India, 6, who died in June 2019 dehydrated because of the extreme heat in the Arizona desert. There are numerous cases of children who die in many diverse circumstances, though not while in custody. These deaths occur because of the risks involved in immigration (insect or serpent bites, drowning while crossing rivers, dehydrated in deserts, suffocated in trailers used by coyotes [smugglers] to transport them, among others). Media do not report the vast majority of these deaths.

Mexico received the first Caravans when it was time to change presidential administration. Therefore, the initial response from the Mexican government included several actions of humanitarian support. Various shelters were equipped along the migrant route. In these shelters, thousands of persons where assisted with food, lodging, clothes, shoes, medical care, and emotional support. Once the new government took office, it issued humanitarian visas for all the migrants who wanted to remain in Mexico. Still, the vast majority persisted in their goal of entering the United States. Hundreds achieved their purpose, and some of them await asylum determination procedures. Even though many of them are in detention centers, others remain in the United States as irregular migrants and face the risk of deportation. Hundreds remain stranded in the city of Tijuana, in the northern border of Mexico, and some others have settled in different states in the country.

The Caravans continued, and, though the number of members varied, the last significant exodus included, in March 2019, more than 3000 people. The Caravans collapsed the Governmental apparatus, which left behind its initial kindness and began raids and procedures of mass detention. Federal agents were deployed, and 6000 members of the new National Guard were posted on roadblocks and checkpoints along the border with Guatemala. In militarizing migration policy, the Government moved away from the human rights discourse used at that time by authorities in mass media. Before, from January 28 2019, the Ministry of the Interior had concluded the Emergency Visitor Card Program for Humanitarian Reasons. It also made a substantial reduction of institutional support for migrants. If that were not enough, although under different conditions, in Mexico, a minor also died in the custody of the National Institute for Migration: Stephanie Velázquez, Guatemalan, 10, who died on May 15, 2019, in the Iztapalapa Municipality Migration Holding Center when she fell from a bunk bed. Just one day before she was transferred with her mother from the State of Chihuahua. The woman was deported with her daughter’s remains.

RUTH

Ruth is a Salvadoran girl, age 10. She describes herself as “tall, pretty. My eyes are green, and my hair is chestnut… and I’m a bit happy… and angry.” Now that she is a migrant, she can make friends more easily. Ruth had to leave her school and friends in El Salvador to migrate with her father to the United States.

Before leaving El Salvador, Ruth loved playing “hide-and-seek” and “mica pelota” with her friends. She also enjoys board games, like bingo or dominoes.

She thinks her country is violent because she frequently saw dead people on the street. Ruth worked in the neighborhood, delivering French fries. She was paid $50 Salvadoran dollars a week, which she spent on food, toys, and she shared a percentage of her earnings with her cousin who came with her on the deliveries.

When she emigrated, she took two pairs of shoes, five pants, five blouses, decorations for her hair, and her two favorite toys: a giraffe and a fluffy duck, which was a present from her grandmother. Ruth confesses she misses her grandmother a lot, and to feel close to her she usually talks to the duck. In addition to missing her loved ones and her dog, Chispita Canela, she reallly misses celebrating holidays like Christmas and New Year’s with her family.

Stories on the Move

Stories of Children in the Caravans

Ruth

Ruth defines herself as “enojada” [angry], what in Mexico we’d call “enojona” [short tempered]. She doesn’t like to be contradicted nor given orders.

“I don’t like people to tell me things, because some say something like: ‘I want you to do this,’ and I say another word, and that’s why I get angry.”

However, she claims to have changed in the wake of migration, because before she found it easy to make friends and understand things. In Mexico, on the other hand, everything is different, and she never stays much in one place. For this reason, she now feels “a bit happy.”

When I asked her how she would describe herself, she answered:

“I’m a Salvadoran girl. I’m 10. I’m tall, pretty. My eyes are green, and my hair is chestnut. My nose is mid-sized. Just that. Uh, and I’m a bit happy!”

What she says is not strange if you know her story. Her parents are divorced. She lived with her mother, her 14-year-old brother, and her stepfather, who owned a vehicle repair shop. Thus, the economic situation of her family was not bad. One day her biological father appeared at her home and invited her and her brother to spend the holidays with his relatives that lived in Guatemala. Ruth’s mother permitted him to take the kids, bus his plan was to actually join the Caravan to Mexico in November 2018, and arrive in California, United States, at an aunt’s house. The aunt had offered to receive them so they could start a new life.

When I interviewed Ruth’s dad, he mentioned his ex-wife was an irresponsible mother. Indeed, he had legal custody of the children. However, because of the crisis in his country, he’d been unemployed for more than a year. For this reason, he had to agree to his kids living with their mother and her new partner. He also said that the stepfather drank too much and had “abusive” behaviors towards Ruth. That made him fear that at some point, he would attack her daughter sexually. Those were the causes that forced him to lie. His ex-wife brought legal action against him, accusing him of kidnapping. The consul of his country in Mexico reviewed the documents in the case and confirmed that he had authority over the children. Therefore, there were no legal reasons to detain him or prosecute him.

The truth was, though his intentions were good, he brought his children to Mexico under false pretenses, causing both of them emotional instability. Also, since he was accompanied, in turn, by his new partner and her two adolescent children, this situation gave rise to daily and recurrent arguments, because Ruth and her brother didn’t accept the father’s partner as a mother figure. Sometimes the kids fought amongst themselves, and this ended in a conflict between the adults. If all the tension brought by factors involved in migration—hunger, thirst, cold, heat, tiredness, potential diseases, uncertainty, fear, discomfort, physical pain, among many others— is added to the situation, it’s not difficult to imagine the mixed feelings experienced by Ruth and her adolescent brother who is 14. Adolescence itself brings about physical and emotional changes that are difficult to manage.

“Sometimes, I get angry. It’s like a part of me tells me to behave, and another tells me not to. It’s like I had a little angel and a little devil in my head […] I’ve changed a lot; for the worse because my attitude has changed, the way I am. The thing is fear gets in me. I’ve changed because of this. I get upset with people. I get upset and fight.”

Ruth had to quit her studies. She was in third grade. In El Salvador, she had many friends, around twenty, boys and girls, though she preferred the company of girls. With her friends, she used to play “hide and seek,” so others would look for her. They also played “mica pelota,” a game that consists of someone holding a ball in one hand and throwing it to someone else, so that player goes after a new candidate who replaces him or her. According to Ruth, they had fun with board games, like bingo or dominoes.

The young girl thinks that her country is “more or less” violent because she frequently saw dead people on the street. “Where I lived, there were often dead persons, because there were gang members and they killed people at midnight and threw them in a plot just opposite from us. They were from the MS-13, from the Mara Salvatrucha.” Ruth believes they didn’t bother her because in the neighborhood where she lived, there were many nearby shops. When she went to the store, she was allowed to go alone. Her mother watched her from a window in their house. According to her, though there were parks close by, neither she nor her cousins were allowed to visit, because her relatives took precaution with the children. Ruth worked in the neighborhood delivering French fries prepared by a neighbor. Every week she was paid 50 Salvadoran dollars that she spent on food, toys and she shared a percentage with her cousin who accompanied her in the deliveries.

The girl remembers that in Guatemala, visiting her father’s relatives, he confessed his true intentions of joining the Caravan.

“My brother started crying, and I didn’t like the idea either, because there, in my country, I do know, and here I don’t.”She still wasn’t aware of what it meant to be a migrant. When they joined the group in Tapachula she felt frightened, “because the people were from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, and I didn’t know them, I was scared; also I had never seen so many persons traveling together. There were about 3000. It was a very uncomfortable trip because we stayed in the street, in parks, and then they pulled people. I mean, they kidnapped people, and some disappeared. That’s what they said […]. I thought they were going to do something bad to us or rape us.”

When I tried to dig deeper to know if she indeed comprehended what sexual violation is, she showed that, although not entirely, she understands it’s physical abuse against her will.

“We ate turkey. Put on new shoes and clothes. We dined with the family. Hit piñatas. In the evening, we ate pupusas (Salvadoran snack). Sometimes we’d go to the beach. I miss those things.”

In Mexico, she has tried new dishes such as “tacos” or “pozole,” which she likes, yet she yearns for the flavors of her country.

Among the most unpleasant experiences during the journey, Ruth remembers the role of Mexican authorities.

“The Mexican police have behaved more or less decently with us. When we were in combis (public transport), they would make us get off, and they would tell us they’d deport us […] I think they should have let us pass, take care of us, not pay attention to us, not look at us, because we don’t do anything to them.”

She also remembers with sadness the first time she had to sleep in the street. Ruth confesses having cried and telling her father she missed her house and that she wanted to go back to El Salvador because she was terrified. However, he calmed her down by promising her that when they settled in the United States, things would improve, and they would be much better than in their “homeland.” Thus, she imagines that the country is beautiful and with many tourist sites since her father’s relatives who live in California regularly send photos of beaches and beautiful places she dreams of knowing soon.

The girl reflects:

“I think that it’s the fault of the Government of El Salvador that people leave, because it didn’t do anything for poor people, and here in Mexico they give us better things, clothes, shoes, food, and there they don’t.”

I asked: “If I could take a picture of you now and you could choose the place, where would you choose?” She answered:

“In a park that looks nice, near a lake. I would like to wear a shirt with a unicorn and this backpack that Santa Claus brought me, with new shoes and these pants I’m wearing, with you or my father.”

Her mom sent her money for Christmas, and her father cashed it through Banco Azteca, with this she bought clothes she wore for the first time on December 24.

Ruth found it very difficult to make new friends because at first, she thought other migrants were terrible people, “ugly,” so she was scared to approach other kids. This changed with familiarity, and though she mixes with others, she tends to fight a lot with them, and it’s frequent to find her angry or crying in a corner.

Kimberly

Kimberly, a member of another Central American Caravan, describes herself as follows:

“I’m nine, I’m Guatemalan; I’m short, dark, my hair is straight. I’m playful, and I have many friends. I have two siblings, a sister 15 and my young brother four. I left many friends in Guatemala, I never worked, I went to school, and I’m happy.”

She confesses that when she emigrated with her family, she experienced fear: “When we were leaving, I did feel a bit insecure.” But staying in Guatemala also frightened her, because she knew hundreds of unfortunate cases, like two girls who were her neighbors that were kidnapped. No one ever heard of them again. Her parents were also victims of violence repeatedly. One time, her dad was on a bike with Kimberley’s siblings, and, to rob him, they put a gun to the four-year-old’s head.

“Since then, we were scared to go out. We stayed at home. Sometimes I went to the store with my uncle, but only because it was in the alley. We walked two, three steps, and we were in the store. My mom took me to school and picked me up.”

In other words, the girl spent her life between her house and school. If she went out somewhere else, she always did it with her parents.

In contrast with Ruth, Kimberly knew the meaning of the word “migrant,” because her mother always spoke about migration, since she didn’t like the job she had in her country.

“My mother worked in a table dance club, but she didn’t dance, she only served the customers; her job was cleaning and serving at the bar. I didn’t go with her to this job. But I did go like three times to her other job, and sometimes I helped her to open drinks.”

At first, the woman wanted to travel to the United States only with the youngest child. She thought that it would be easier to seek asylum, but she set the idea aside due to the constant warning of relatives and friends, who explained the dangers involved in that movement. When she heard about the Caravans, she convinced her husband to join, because at that time they were already living in Mexico.

The family had emigrated before in the exodus of October of 2018, because one particular night when she went to pick up her husband at the end of work, they witnessed a shooting that ended with the murder of a young man. The criminals were neighbors that knew the couple and where they lived.

“The next day they came to our house shooting and all of that, so we decided better to come together. Both my parents had to leave their jobs, and my siblings and me, school. I was in third grade, and what I liked the most was to paint, I mean, the visual arts class. Oh, and also math!”

That last episode of violence forced Kimberley’s family to emigrate. She remembers that their trip was delayed because the driver of the bus they took from the capital city towards the border community of “El Naranjo” was drunk, made constant stops, and for this reason, they arrived late at their destination. Later they boarded another bus towards “El Ceibo,” where they stayed three days. There, her mother got a permit to enter Mexico legally as a visitor. Still, it only lasted seven days, and the authorization was limited to five states in the southern border region. They then arrived in Cancún, Quintana Roo, where they remained for almost six months in an irregular situation, while her parents worked, trying to get money to continue the trip.

As she did in Guatemala, Kimberly lived in the port of Izabal. She was used to the heat and the sea. She states that she enjoyed her stay in Cancún very much. But that didn’t diminish the sadness of leaving everything behind.

“The thing is we left without telling anyone a thing, not even our family. The day after we left, my mother called my granny and told her to grab any things in our house that she’d find useful, and to keep our clothes and stuff like that for us. For this reason, my grandmother is taking care of our things in her house, because we rented that house. We didn’t have a house of our own.”

Kimberly said that she misses her family, her school, her teacher, and her friends a lot: “I had to forget about them.” She also longs for the sea, “that beach that filled with black people dancing ‘punta’ (Garífuna dance), the rivers, the waterfalls,” but among all, what she misses the most, undoubtedly, is the presence of her grandmother. “When we departed, I felt sad because I left my granny and couldn’t say goodbye to her. My sister and I felt very sad, but since my younger brother is young, he doesn’t understand a thing. Each time we took a bus, he only repeated that we were closer to Guatemala.”

Speaking of food, she yearns for flour tortillas, pizza, and Guatemalan instant soups, because she thinks the Mexican ones don’t compare to those. Like Ruth, among special moments, she also recalls Christmas as one of the most beautiful and significant times. She remembers going to mass with her parents, dining with the family, and having fun opening presents with her cousins and siblings, until dawn and “setting off firecrackers.”

In 2018, for the celebration, her grandmother sent money to Kimberley’s mother via MoneyGram. They could reload the family’s cellphone and make video-calls exchanging congratulations. Kimberly’s mother doesn’t want her kids to forget their loved ones, so she tries to phone her relatives any time she can or “connect through video,” so the children can see their granny and keep her in mind. “My favorite relatives are my uncle and my grandmother because they treated me very affectionately.”

At the beginning of 2018, since Kimberly’s parents didn’t know that the Caravans would be organized, they left for Mexico with a considerable amount of clothes. When they decided to join the migrant group, they traveled to Villa Hermosa, Tabasco, and then to the capital of Mexico. They arrived at night and didn’t know the city. Unfortunately, they were mugged near the hotel where they planned to stay. After they lost what they had saved in Cancun and having nothing left, they had to sell their clothes and bags to pay for two hotel nights and meals. By that point, the Government of Mexico City had adapted a temporary shelter. The family went to the shelter and, from that date, joined the rest of the members of the Caravan.

“With a group of other migrants we’ve been in shelters like the Estadio Palillo, in the Ciudad Deportiva, the Casa del Peregrino, the Faro Tláhuac, the Casa de los Adultos Mayores, in Álvaro Obregón, but before we passed by other places like Huixtla and Tapachula, and many parts, but I don’t remember clearly the name of all the places.”

When I asked with whom and how she would like to be photographed, she answered:

“I would like to be alone, in the Angel of Independence (Mexico City’s symbolic sculpture) and I would have to choose my prettiest clothes.”

I asked her about her musical taste she shared that her favorite song goes something like this: “I was barefoot. I don’t want rich friends, much less fake [friends],” but she couldn’t remember the singer’s name.

Regarding migration, she thinks that many Guatemalans leave their country because they have relatives in the United States and want to join them. She also thinks her country’s Government is responsible because it doesn’t help them to get jobs.

“Some people go to companies, and they ask them to be of legal age and have all their papers and those hard-to-get things. Once, my father spent a long time without a job.”

She also confesses that a thing she doesn’t like in her country is racist people.

Where I lived, they spoke indigenous languages like Quiché or Garifuna, but I didn’t learn it […] I noticed discrimination when they mistreated a person because of their skin color or for speaking a different language. In school, I had a friend who spoke the Kakchiquel language, and a classmate told him not to talk in that awful language, and he felt sad. I told the director what she had said, and she explained to my classmate that it was a beautiful language, that all Guatemalans should know.

She remembers witnessing discriminatory attitudes in Mexico, but she puts it down to the fact that they seldom go beyond the shelters. Also, when they have traveled by bus, it’s always been nighttime.

“Since we are snoring on the bus, I don’t notice [also], we’ve always been well-dressed during trips, no Lycras nor stuff like that. My mother puts a dress on me. Once in Veracruz, people from the checkpoint got on, and they took some people with them, but not us. The policeman stared at my dad, but since he was asleep, he left.”

Kimberly mentioned that she had met people who ask her if she feels bad because she was born in Guatemala. She always answers the following: “Maybe your country is ugly, but mine is not.”

In Mexico, she likes to visit malls and supermarkets like Walmart and Chedraui, “just to browse, because we are poor and we cannot always buy, but at least we amuse ourselves looking at things.” Among her plans for the future, she also sees her family in the United States, a country she imagines full of big cities and many cars.

“I’m going to study there, and when I finish, I’m going to build my mom a huge house. But I would also like to meet my family from Guatemala again. I know we are going to cry a lot.”

Caravans

Between Solidarity and Rejection

First Wave

The first wave of the Caravan included about seven-thousand people, with a “strong showing of women, children, senior citizens, families, mainly from Honduras” (Gandini, 2019: 24). It happened at the same time as Mexico’s transition to a new government and overall people were supportive.

OCTOBER 2018

Second Wave

The second wave of the Caravan had “around thirteen-thousand people of Central American origin, with a more diverse involvement of nationalities” (Gandini, 2019: 25). The Government was welcoming to the caravans and offered humanitarian visas and the possibility of beginning the refugee process for those who were considering it.

JANUARY 17, 2019

Third wave

Approximately three thousand people arrived in small groups during the third wave and the official attitude changed. This included an abrupt end to the emergency visitor card program for humanitarian and a hostile government position. Detention procedures begin and control measures and police presence increase (Gandini, 2019: 26-28).

MARCH 30, 2019

Caravans were made up of very wide-ranging groups. People of all ages and different social classes, with various vulnerabilities, traveled in the Caravans. The unifying element was forced migration. Traveling together as a group represented a protection strategy since group exposure helped to reduce dangers and costs. Also, it provied them with more prompt attention from authorities. Though the inherent risk of deportation existed, there was also a higher probability of achieving their goal of reaching the United States.

Several media claimed that this massive mobilization had been manipulated and financed, to a great extent, by characters with political and economic interests, since the main expulsion dates coincided with the U.S. mid-term elections, as well as the new Mexican Government transition. According to some analysts, one intention was to destabilize the new Mexican presidential administration.

The fact is that, although there may be Central American persons that benefit economically from this juncture, the common denominator didn’t have this profile. In most of Central America, structural causes have favored unsustainable conditions of dispossession, misery, violence, insecurity, and corruption, that today force thousands of human beings to flee and look for better opportunities and living conditions. Moreover, migrants are increasingly aware of their rights. For this reason, through caravans, they demanded their rights not only for them but also for those who will follow.

Though at times, there was a trace of institutional support, most of the time, the Mexican Government used strategies focused on deterrence, the emotional exhaustion of migrants, contention, and division in the Caravans. Humanitarian help came mainly from civil society and religious organizations. Despite the conditions of vulnerability for lack of food, lodging, medicine, or security of the more significant part of the exodus, and besides being exposed to severe weather, authorities were dismissive when they denied international protection even to girls, boys, and adolescents. One of the orders given consisted in denying entrance to unaccompanied minors at the border.

At first, there was no coordination in the measures taken, and each authority at the state level responded according to its political will. Furthermore, the temporary shelters installed for the emergency did not fulfill the necessary conditions nor the health requirements. The lack of care, overcrowding, and adverse conditions during the journey caused, in every Caravan, various infectious diseases: skin, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and other types of illnesses, primarily in girls, boys, adolescents, women, and the elderly.

The show of solidarity greatly diminished while hostile and discriminatory attitudes grew. The inhabitants of cities like Tijuana organized rallies against these exoduses. At the same time, individual municipalities in Chiapas and Oaxaca took part in xenophobic acts, like fumigating migrants while they slept in the streets or open spaces, fearing they were carrying viruses and could spread epidemics. In Ayutla, Tecún Umán, inhabitants armed with sticks and stones forced the group that assembled in the town center to flee from that border. Human rights defenders and activists were harassed for their work and criticized by the public.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump threatened to impose and increase tariffs on Mexican products, which would generate a severe economic crisis in the country. To avoid this crisis, both administrations reached an agreement on June 7, 2019. Mexico agreed to stop migrant flows and to receive more than 10 000 Central American asylum seekers waiting for the U.S. to issue a resolution. Despite the fact that Mexican Law doesn’t authorize the reception of third-country returnees in theory, which refers to non-Mexicans whose repatriation is ordered by another country, this measure is being carried out in practice for returnees from the United States.

At the end of the Caravan critical juncture, the United States provided Mexico with facilities to become a de facto “third safe country.” This despite not having appropriate legislative or infrastructure mechanisms, and even though with this the State is neglectful and ends up violating international refuge statutes. These measures are turning the southern border, symbolically, into the wall that Trump yearned to build. In the first eight months of 2019 alone, 38 291 asylum seekers in the United States were returned to Mexico. The majority are still waiting for their first hearing in court at various ports of entry. Asylum procedures in an immigration court of the United States currently last, on average, more than 700 days. That is, for more than two years, asylum seekers sent back to Mexico must await their hearing in this country, generally without any economic support and high-risk conditions.

In this way, the new pact between the two countries laid the foundation for the future immigration policy of the new Mexican Administration: serving the interests of the United States and helping to preserve the country’s much-desired “national security.” Amidst the back-and-forth of political negotiations, the lives of girls, boys, and adolescents—that voluntarily or involuntarily were part of the Caravans and keep adding in number to the unstoppable population flows—are disrupted in several ways. They’re also exposed to innumerable dangers in the face of the insensitivity of some, the needs and dreams of others, and the economic and political interests of still a few others.

By the Numbers: Caravans

People were involved

Refugee claims were made

Children refugee claims

Why Does it Matter?

The has constantly been forced migration of Central Americans to the United States for more than three decades. Collective migrant mobilizations like the caravans have been caused by migration policies, the closing of borders, and violence against people who migrate. Migrants travel together to accompany and protect one and other. These movements captured media attention and caused a crisis in border health and humanitarian aid systems.

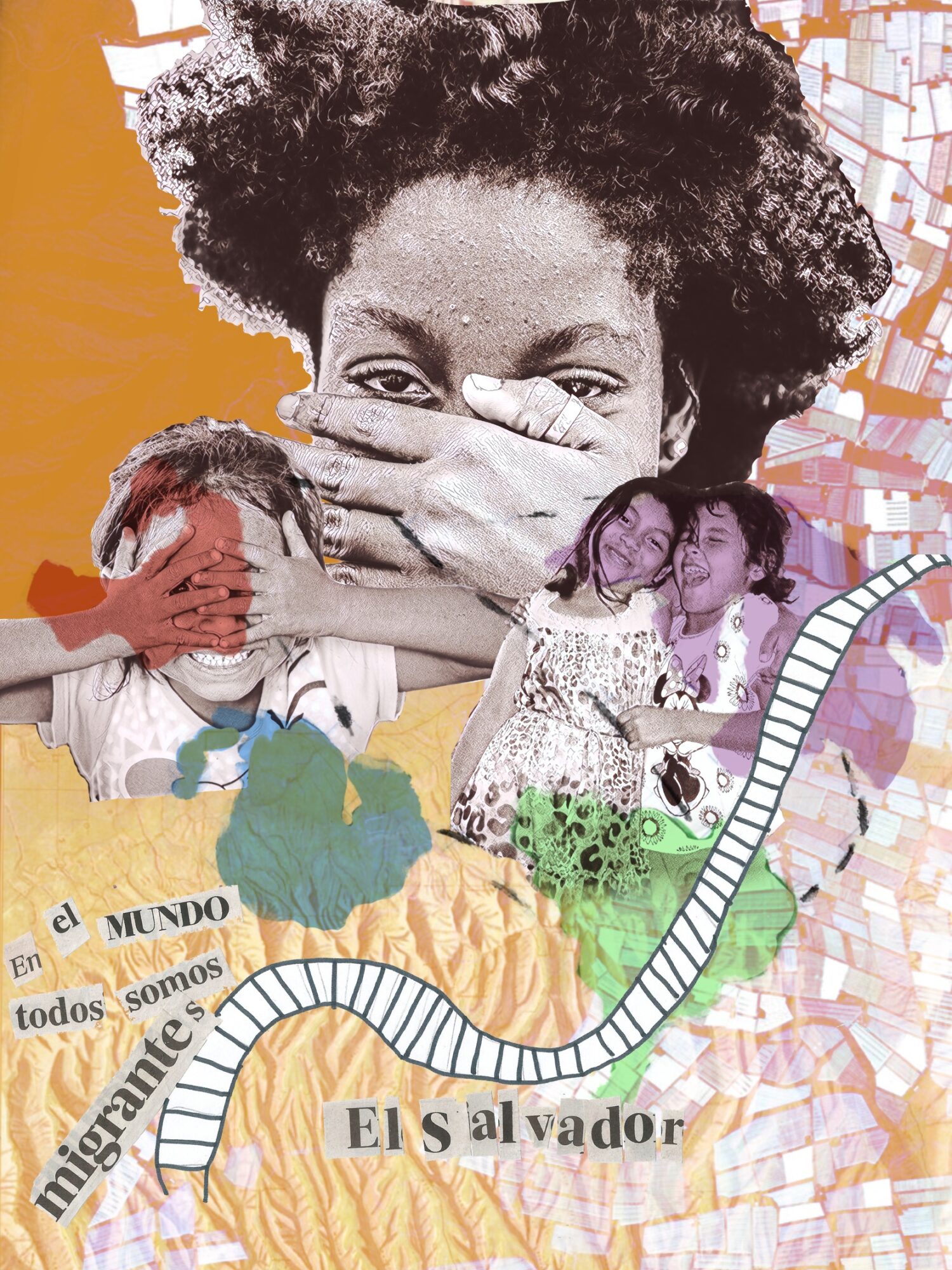

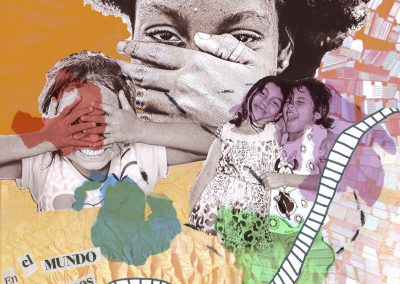

Images of children in these mobilizations show us the gravity of the circumstances.

A Picture of the Situation

There are almost 3000 child refugee claims from these migrant mobilizations. The initial solidaity for the first caravans has lessened because of hate speech and xenophobia that have largely been promoted by irresponsible politicians and reproduced by mass media. This situation translates into a separation narrative and paints an image of migrants as dangerous.

The situation also justifies racist and exclusionary policies that directly impact the lives of millions of families and the lives and stories of thousands of children.

How to Get Involved

Solidarity is part of our humanity, not of institutional discourse. Reclaim it! These mobilizations remind us of the importance of supporting and taking care of each other.

Listen carefully to the voices of these boys and girls, that push us to create more equitable worlds. Connect with the people who are building these safe spaces for those involved in the caravans.

Footnotes

- También existe la “Caravana centroamericana de madres de migrantes desaparecidos”, que desde hace 14 años viaja consuetudinariamente a México para dar seguimiento a los casos de sus hijos, cuyo paradero aún se desconoce.

- Desde finales del siglo xx, la Parroquia de Cristo Crucificado abrió sus puertas para dar hospedaje y alimento a las personas migrantes. El 25 de abril de 2011 el albergue se trasladó de la casa parroquial a su actual sede y fue nombrado “La 72, Hogar-Refugio para personas migrantes”, en honor a los 72 centro y sudamericanos asesinados en San Fernando, Tamaulipas, México, por el cartel de “Los Zetas”, entre el 22 y 23 de agosto de 2010, exterminio que continúa impune. Véase “Historia”, La 72. Hogar-Refugio para Migrantes. Tenosique, Tabasco (sitio de internet), s/f. Recuperado el 10 de junio de 2019 de https://la72.org/historia/

- Entrevista con el director del Albergue “Hermanos en el Camino”, 16 de abril de 2017; Petrich, Blanche, “El Viacrucis surgió por la violencia contra migrantes”, La Jornada, 25 de abril de 2014, p. 9.

- “Cronología especial sobre política migratoria. Reporte especial sobre la crisis de los niños migrantes y separación de familias en Estados Unidos y su impacto en los procesos migratorios en América del Norte (junio-octubre de 2018)”, Observatorio Norteamericano CISAN, México, CISAN-UNAM, 4 de octubre de 2018.

- “6 niños migrantes han fallecido bajo custodia de EUA” (archivo de video), NowThis Español (Facebook), 24 de mayo de 2018. Recuperado el 14 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://www.facebook.com/NowThisEspanol/videos/2106398399657201/ ;“Dedican altar a niños migrantes que murieron cruzando la frontera con México”, La Jornada maya, 1 de noviembre de 2019. Recuperado el 14 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://www.lajornadamaya.mx/2019-11-01/Dedican-altar-a-ninos-migrantes-que-murieron-cruzando-la-frontera-con-Mexico ; “New Video Shows Border Patrol Account of Child’s Death Was Not True” (archivo de video), ProPublica (YouTube), 5 de diciembre de 2019. Recuperado el 16 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YN_CXOS3yuc&feature=youtu.be&fbclid=IwAR2ZM1cfT3GjmwV_u38WdwNwjhaoGsOCbAKQ5f_j69kILPFyHX3I6HE_AIE&app=desktop ; “Muere niña guatemalteca de diez años bajo custodia del Instituto Nacional de Migración de México”, Wola, 20 de mayo de 2019. Recuperado el 18 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://www.wola.org/es/2019/05/muere-nina-migrante-instituto-nacional-migracion/ ; Alejandra Natalia Rodríguez, “Seis menores migrantes murieron bajo custodia de EU y México”, CC News, 21 de mayo de 2019. Recuperado el 18 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://news.culturacolectiva.com/mundo/seis-menores-migrantes-murieron-bajo-custodia-de-eu-y-mexico/ ; “La sociedad civil de México y Estados Unidos llamamos a un alto al sacrificio de vidas migrantes” (comunicado), Hispanics in Philanthropy (sitio de internet), 21 de mayo de 2019. Recuperado el 20 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://hiponline.org/la-sociedad-civil-de-mexico-y-estados-unidos-llamamos-a-un-alto-al-sacrificio-de-vidas-migrantes/ ; Dean Obeidallah, “La muerte de una niña de 10 años en custodia de Estados Unidos sería el peor encubrimiento de Trump”, CNN en Español, 27 de mayo de 2019. Recuperado el 20 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2019/05/27/la-muerte-de-una-nina-de-10-anos-seria-el-peor-encubrimiento-de-trump/ ; Catherine E. Shoichet, “La corta vida y el largo viaje de una niña de la India, de 6 años, que murió cerca de la frontera entre EE. UU. y México”, CNN News, 25 de junio de 2019. Recuperado el 20 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2019/06/25/la-corta-vida-y-el-largo-viaje-de-una-nina-de-la-india-de-6-anos-que-murio-cerca-de-la-frontera-entre-ee-uu-y-mexico/

- Información difundida en las redes sociales por la Misión de Observación de Derechos Humanos de la Crisis Humanitaria de Refugiados y Migrantes en el Sureste de México, 29-31 de mayo 2019.

- Ana Langner, “En 8 meses, EU regresó a México más de 38 mil migrantes que esperan asilo”, La Jornada Baja California, 3 de noviembre de 2019. Recuperado el 18 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://jornadabc.mx/tijuana/03-11-2019/en-8-meses-eu-regreso-mexico-mas-de-38-mil-migrantes-que-esperan-asilo

References

“6 niños migrantes han fallecido bajo custodia de EUA” (archivo de video), NowThis Español (Facebook), 24 de mayo de 2018. Recuperado el 14 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://www.facebook.com/NowThisEspanol/videos/2106398399657201/

“Cobertura Caravana Migrante”, Observatorio de Legislación y Política Migratoria, México, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, octubre de 2018 a abril de 2019. Recuperado el 29 de abril de 2019 de: https://observatoriocolef.org/?theme=caravana

“Cronología especial sobre política migratoria. Reporte especial sobre la crisis de los niños migrantes y separación de familias en Estados Unidos y su impacto en los procesos migratorios en América del Norte (junio-octubre de 2018)”, Observatorio Norteamericano CISAN, México, CISAN-UNAM, 4 de octubre de 2018. Recuperado el 18 de octubre de 2018 de: https://cisanunam.blogspot.com/2018/10/cronologia-especial-sobre-politica.html?fbclid=IwAR0bP-hf0J0YGep6HYBPtuuOZLFipRt6F_f58nqr2gJz8a0_6Gps_CesRYE

“Dedican altar a niños migrantes que murieron cruzando la frontera con México”, La Jornada maya, 1 de noviembre de 2019. Recuperado el 14 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://www.lajornadamaya.mx/2019-11-01/Dedican-altar-a-ninos-migrantes-que-murieron-cruzando-la-frontera-con-Mexico

“La sociedad civil de México y Estados Unidos llamamos a un alto al sacrificio de vidas migrantes” (comunicado), Hispanics in Philanthropy (sitio de internet), 21 de mayo de 2019. Recuperado el 20 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://hiponline.org/la-sociedad-civil-de-mexico-y-estados-unidos-llamamos-a-un-alto-al-sacrificio-de-vidas-migrantes/

“Historia”, La 72. Hogar-Refugio para Migrantes. Tenosique, Tabasco (sitio de internet), s/f. Recuperado el 10 de junio de 2019 de https://la72.org/historia/

Langner, Ana, “En 8 meses, EU regresó a México más de 38 mil migrantes que esperan asilo”, La Jornada Baja California, 3 de noviembre de 2019. Recuperado el 18 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://jornadabc.mx/tijuana/03-11-2019/en-8-meses-eu-regreso-mexico-mas-de-38-mil-migrantes-que-esperan-asilo

“Muere niña guatemalteca de diez años bajo custodia del Instituto Nacional de Migración de México”, Wola, 20 de mayo de 2019. Recuperado el 18 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://www.wola.org/es/2019/05/muere-nina-migrante-instituto-nacional-migracion/

“New Video Shows Border Patrol Account of Child’s Death Was Not True” (archivo de video), ProPublica (YouTube), 5 de diciembre de 2019. Recuperado el 16 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YN_CXOS3yuc&feature=youtu.be&fbclid=IwAR2ZM1cfT3GjmwV_u38WdwNwjhaoGsOCbAKQ5f_j69kILPFyHX3I6HE_AIE&app=desktop

Obeidallah, Dean, “La muerte de una niña de 10 años en custodia de Estados Unidos sería el peor encubrimiento de Trump”, CNN en Español, 27 de mayo de 2019. Recuperado el 20 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2019/05/27/la-muerte-de-una-nina-de-10-anos-seria-el-peor-encubrimiento-de-trump/

Petrich, Blanche, “El Viacrucis surgió por la violencia contra migrantes”, La Jornada, 25 de abril de 2014, p. 9.

Rodríguez, Alejandra Natalia, “Seis menores migrantes murieron bajo custodia de EU y México”, CC News, 21 de mayo de 2019. Recuperado el 18 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://news.culturacolectiva.com/mundo/seis-menores-migrantes-murieron-bajo-custodia-de-eu-y-mexico/

Shoichet, Catherine E., “La corta vida y el largo viaje de una niña de la India, de 6 años, que murió cerca de la frontera entre EE. UU. y México”, CNN News, 25 de junio de 2019. Recuperado el 20 de diciembre de 2019 de: https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2019/06/25/la-corta-vida-y-el-largo-viaje-de-una-nina-de-la-india-de-6-anos-que-murio-cerca-de-la-frontera-entre-ee-uu-y-mexico/

Las ‘oleadas’ de las caravanas migrantes y las cambiantes respuestas

gubernamentales. Retos para la política migratoria”, en Fernández de la Reguera Ahedo, Alethia et al. Caravanas migrantes: las respuestas de México, México, IIJ-UNAM, 2019, pp. 23-31.

Instituto Nacional de Migración. (2019, febrero 8). INM: Solicitudes Tarjetas de Visitante por Razones Humanitarias 17-29 enero 2019. Recuperado 7 de mayo de 2020, de https://observatoriocolef.org/infograficos/inm-solicitudes-tarjetas-de-visitante-por-razones-humanitarias-17-29-enero-2019/