FRAGMENTED FAMILIES

Forced Separation Due to Detention and Deportation

Family separation and migrant detention under President Donald Trump’s administration traveled around the world as a news piece, including videos and images that showed children separated from their mothers, locked in cages, and crying.

A growing number of migrant families and children remain separated and in indefinite punitive detention in the U.S. Families are still being separated, despite the Trump administration’s official announcement of the end of its “zero-tolerance” policy. Fathers are imprisoned in detention centers. Children are sent to places such as shelters (detention centers for minors) or to foster homes thousands of kilometers away from their mother or father, many times without news of one another. The U.S. federal government and several “non-profit” organizations, including religious institutions, manage these shelters. According to the ProPublica news website, before the announcement of the “zero-tolerance” policy, these places accommodated almost “8886 unaccompanied children.”

Detention spaces for migrant children include a wide variety of facilities, from foster homes, shelters, border patrol stations, to detention centers.

Some of these facilities resemble warehouses. One example is Casa Padre, in Brownsville, Texas, a Walmart converted into a shelter for unaccompanied minors, where there are around 1500 migrant children. Another example is Tornillo Tent City (a temporary facility built in 2018), a temporary detention center for migrant children located at the border in Tornillo, Texas, and operated by the Office of Refugee Resettlement of the Department of Health and Human Services. Some of these shelters are managed by organizations like Southwest Key, which for twenty years have been running reception places that shelter unaccompanied migrant boys and girls under 18 years of age. This facility is part of the federal shelter system created as a result of the 1997 Flores Settlement Agreement. Southwest Key has more than thirty shelters in the states of Texas, California, and Arizona.

However, family separation is not a recent problem in the United States, nor is it limited to the border region. Separations also occurred during the Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama administrations. “In 1986 Reagan deported around 24 592 people, or 0.76% of the total undocumented population in the country, estimated at 3.2 million. During the George H. W. Bush Administration, there were 141 316 deportations. Also, in 2005, the construction of the first family detention centers began. With Barack Obama, 2.7 million immigrants were expelled from the country, despite his government opting for not separating families that crossed the border with their children”.

Forced family separation and deportation have a considerable number of negative impacts, not only for deportees, but also for the extended families and communities they leave behind and, especially, on boys and girls.

“Obama, not Trump deported my mother,” says Michelle, a twelve-year-old girl who faced her mother’s deportation to Mexico when she was five, together with her older sister Heidi. The two girls had to live without their mother for three years and to cope with her absence at a very young age.

We lived with my dad only, but he worked all day to pay the rent. I spoke to my mom on the phone. We’d see each other through Facetime. I felt very frustrated when they deported my mom. It was tough to understand what was happening. I remember that one time she tried to cross the border and told me she’d come for my birthday; she couldn’t because the immigration people got her, and they put her in a detention center. That day was very sad. I felt I was losing hope.

For a long time, Michelle and her family looked for help to reunite their family in New York. Together with Heidi and her dad, they organized a family reunification campaign with the New Sanctuary Coalition organization, intending to bring her mother back to New York City. She was only seven, and her sister Heidi was 15. Michelle recounts it as follows:

In 2016, we left for the border with my father Juan Carlos to bring my mother because I had to claim my right as a citizen of this country. We crossed my mother in a caravan [including migrants, activists, and faith leaders], and all those people supported her. My sister and I took my mother by the hand, very firmly, and together with all those people supporting us, we crossed a bridge. And my mother requested asylum. Today I’m happy because I have my mother.

The two sisters have friends and relatives that were also separated from their mothers because of deportation.

I see the images of children in cages, and I felt sad because I know how it feels to be separated from one’s mom. I would like to say to those children that everything is going to be alright. In my case, being separated from my mom made me mature, grow, I wasn’t any girl, because I couldn’t enjoy my mother’s hugs. My birthday was very sad without her. I was left behind in school. I cried a lot. I felt very sad because when they separate a child from his or her mom, it is very sad. I don’t wish that for another child.

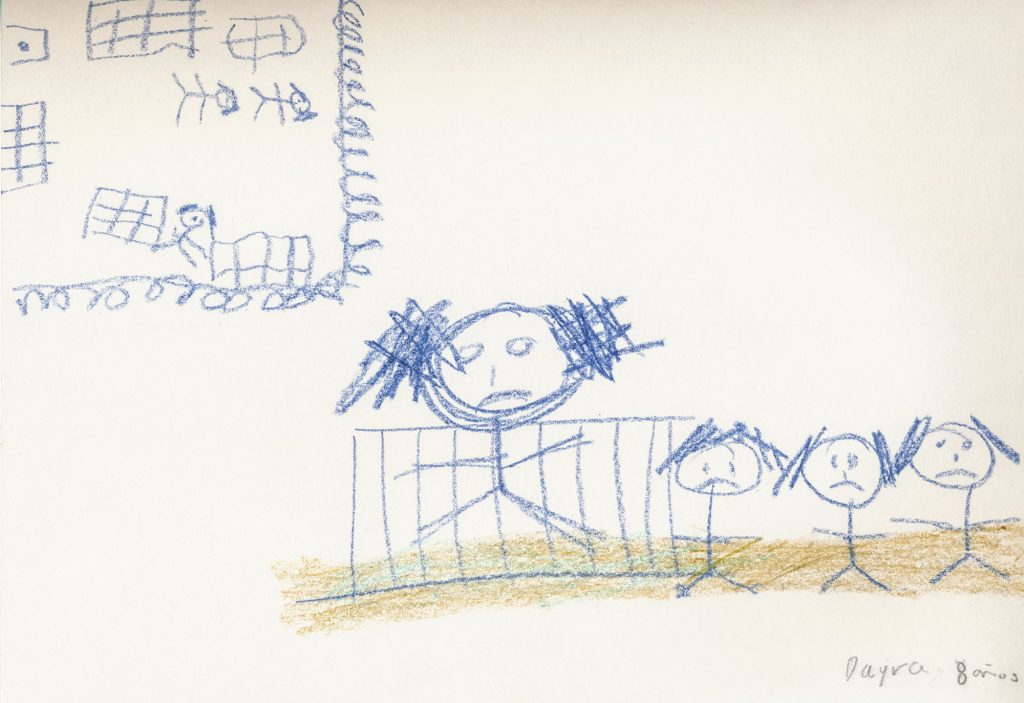

Lady, Daira, and Alan

“We arrived in Arizona. There, immigration authorities got us. We surrendered. He requested asylum. Even then, they jailed us, and we were separated.”

After more than a month in the Eloy Detention Center in Arizona, together with other mothers who had also been separated from their children, Daisy heard of a lawyer who helped women like her get out of “jail” and recover their children.

HOW DOES ZERO-TOLERANCE FEEL LIKE

Psychological and Emotional Consequences of Migrating “Covertly”

Obama, not Trump, deported my mother.

For many girls and boys, family separation and living under the pressure and anxiety of the potential deportation of their parents at any time, has transformed their lives and childhoods dizzily. As a result of this experience, they begin to position themselves politically and become their family’s, neighborhood’s, and community’s spokespersons. Amid leaders of faith, activists, lawyers, and pro-migrant organizations, they learn to “fight” for their rights, without forgetting to make space for games, laughter, and fun.

Family separation is equivalent to making the father or mother disappear from the household. Returning home from school, the boy or girl realizes that his or her mother is not there, that she has left, that the immigration agents have detained her to deport her later. Suddenly, in a few hours, that child is left motherless. In other cases, the father cannot return home because immigration agents detain him in a raid at his job and deport him. Forced family separation exposes children to an uncertain future.

But what differences and similarities exist between family separation caused by deportation, those due to economic displacement, and those resulting from zero-tolerance politics? How do they cast and shape migrant children’s human experience? How do the infrastructure and machinery for family separation and detention configure children’s social interactions, well-being, and mental health?

There, I saw adolescents shackled and handcuffed. They didn’t handcuff me because I was a young girl still. In the coolers they never turn the lights off, it’s cold. The food they give you is frozen. It’s always the same, frozen burritos. You cannot sleep because of anxiety. You have the right to one phone call only. If they call your name and you are not awake, too bad, you lost your call. This cooler was infested with lice and bedbugs. They treat you awful. I saw very young boys, around 3, 5, crying.

When I was detained, I didn’t know anything about my aunt. I was sad for all I had to go through to be with my mom. They don’t give you anything to wrap yourself with, only some kind of aluminum blanket now and then. I had ticks. There,one feels awful. You don’t know if its day or night.

Hazel recalls that it was only after a few weeks of “imprisonment” when she could speak to her mother and tell her she was alive.

I remember it was a day when many children arrived. They were wet, with mud. I went from one cooler to the next for some time, until they sent me to a foster home in San Antonio for about two weeks. There I was less worried. I had a bed for myself. They treated me very well. I saw a psychologist because I was crying all the time. There, I went to school. They fed me. You can watch T.V. The people took care of me. I met many girls who had been in that shelter home for almost a year. It was very hard for them. There, I felt good. They gave me hope that soon I would be with my mom.

Since 2015, Hazel lives with her mother in Haven, Connecticut, and recently she became a U.S. resident. It’s also been a while since she’s been involved in the Unidad Latina en Acción organization and works as an activist with families sheltered in “sanctuaries,” and fights against family separation.

For Hazel, there are many psychological and emotional consequences of “concealed” migration.

To be “imprisoned” and separated from your family. Even if you don’t ‘migrate’ and are imprisoned, growing up without one of your parents generates an emptiness and a “trauma” during childhood. When you are a young child, you don’t understand why your mother migrated and left you alone. Also, we have very intense feelings of abandonment. And one doesn’t forget that.

Under the Trump administration and its heavy-handed approach on migration—called “zero-tolerance policy”—family separation has had an impact on thousands of families. Betty’s is one case: a single mother from El Salvador who migrated to the United States to flee the mara’s gang violence. Her son’s father, a marero [a mara gang member], sexually abused her several times until she got pregnant. And even while he was in jail for years, he controlled her movements,

“He threatened to kill me if I didn’t visit him in prison.”

When Betty crossed the U.S. border with Juan, her three-year-old son, immigration agents took her to a detention center in El Paso. In that place, “the policewoman” [sic] told her to hand her son over to bathe him as she couldn’t get out of her cell.

“I handed her my son, the same as other mothers. We didn’t think they would separate them from us.”

Betty didn’t hear from her son until three months later. She kept asking immigration agents,

“Where is my son?” They’d answer highhandedly, “What son? You didn’t bring a son with you. Go to your country. You people are like roaches.”

After being separated, Betty noted a change of behavior in her son. Juan didn’t want to be with her and was aggressive towards his mother. “He cried for whatever reason. He wasn’t the same boy I was separated from.” Juan had suffered an emotional trauma caused by the separation:

“Just imagine, we traveled from El Salvador up to the border. He was so quiet, so calm. He wasn’t like this. He wasn’t like this.”

The practices and procedures against people seeking asylum and refuge in the United States have intensified as a result of the “zero-tolerance” policy. When migrants seek asylum after crossing the border and undergo the “credible fear” interview, they are imprisoned for an indefinite time in detention centers, separated from their children, while they await an answer from the immigration authorities, or are in some cases set free. Sometimes they are allowed to leave detention, but under supervision and have to wear an electronic ankle monitor, like Betty.

Lady, Daira and Alan

Seek Asylum, Get Detention

Another case is Daisy’s, also a Salvadoran single mother, who, like Betty, was separated for three months from her three children. Lady, 15, Daira, 8, and Alan, 5. “We arrived in Arizona. There, immigration authorities got us. We surrendered. He requested asylum. Even then, they jailed us, and we were separated.”

After more than a month in the Eloy Detention Center in Arizona, together with other mothers who had also been separated from their children, Daisy heard of a lawyer who helped women like her get out of “jail” and recover their children. A new friend she met in “jail,” gave her lawyer Ricardo de Anda’s phone number and told her, “Call him. You’ll see, he’ll help you.” Daisy didn’t hesitate and phoned the lawyer.

She was separated from her children in entering the detention center. When she asked the policemen for them, they answered mockingly, “Which children? You didn’t come with any children.” “That’s what happens for being illegal. Go back to your country.” She cried disconsolately. She was desperate and anxious to learn about her children. Other mothers in a similar situation expressed their solidarity. They told her, “Don’t worry. You’ll see your children again. Have faith in God.”

After speaking to the lawyer, Daisy heard of their whereabouts. Immigration agents had sent them to Abbott House, a foster parents’ agency in New York City. Abbott House is a specialized private organization working with a program called Transitional Resources for Children, TRC. It has care centers for immigrant children entering the United States “without an adult guardian.” They are sheltered there for a brief time while a family member is identified. During their stay, children receive room and board, counseling, medical, and educational services, and case management.

Can I hug you? Are hugs allowed now?

However, these foster parents’ agencies have aroused controversy. As a result of family separation, activists, politics, religious institutions, and leaders have organized rallies and press conferences to denounce that most migrant children in shelter homes entered the United States with their parents or a relative. Furthermore, they have reported that the U.S. government uses these centers as an instrument to separate migrant families, and at the same time, they serve as a lucrative business. Other agencies receive children separated from their parents at the border: Cayuga Centers, Southwest Key Programs, Rising Ground, Jewish Child Care Association, Foster Care Center, Casa San Francisco, and so on.

In March 2019, Daisy met her two children, Daira and Alan, again in Abbott House. Lady, the eldest, was put in a psychiatric hospital without her consent. “My daughter couldn’t cope emotionally with separation; the trauma was intense.”

During her stay in New York, Daisy and her family got help from Sanctuary Neighborhood, a migrant support network involving members of civil society, activists, and religious leaders.

After a week of attending the Manhattan psychiatric hospital where her daughter was confined, Daisy succeeded in having the doctors discharge her. Lady was quiet and, at the same time, moved. She thought she wouldn’t see her mother and siblings again.

When he saw her, Alan asked, “Can I hug you? Are hugs allowed now?” Daisy didn’t know why he had asked her daughter that. “Because in the jail we were, they wouldn’t let us hug each other. The ladies that took care of us said hugs were not allowed,” he told her.

Lady asked her mother if she could take her to see the Statue of Liberty. On that trip, they talked about their plans, of their life together as a family, and she said she was happy to be “free.”

When the ‘policemen’ had us in jail, Daira got very ill. She caught a skin infection, a fungus. She got blisters on her hands. I felt sad, very sad. The place they had us in was awful, like a cell.” And she cries out excitedly, “Look, look, the statue is there. It feels nice to see her from the boat. It’s the first time we’re on a boat. In El Salvador, it’s only for rich people!

Daisy asked her children,

—”Over there in jail, what did you do? How did you sleep?

“They gave us plastic bags for sleeping. There were many children.” Daira answered.

“Was it there where you got the lice?”

Daira only nods and answers,

“I don’t know where, mom.”

Daira sólo mueve la cabeza y responde:

—No sé dónde, mamá.

Streamline

“McDonaldize” Deportation

In 2005 the “Streamline” operation entered into force. It’s a program implemented at a stretch of the Texas border, specifying that all immigrants entering the United States unlawfully or in an “illegal” manner would be processed as criminals and imprisoned to expedite their trials and thus, deport them more quickly.

This initiative soon spread to other places at the border. At that time, however, exceptions were made for adults that crossed with their children or infants, and for minors and sick persons.

Under President Trump’s Administration and the “zero-tolerance” policy, the tactic to punish and terrorize families that crossed the border with their children was to separate and imprison them in detention centers (“jails”) thousands of kilometers apart. This was done while they prosecuted and criminalized the children’s mothers or fathers for seeking asylum or crossing the border “illegally.

Against a background of increasing national and international pressure, President Trump signed an executive order to stop the separation of children from their parents at the border. However, months after revoking the “zero-tolerance” policy, families are still separated at the border.

The Federal Government identified more than 2737 children separated from their parents because of this policy, and to date, more than 15 000 are not with them.

Lady says,

In Abbott House, there were girls like me. They have us jailed, and then they take us to the homes of people we don’t know and who take care of us. Some girls have been there for a year, waiting to see their moms. One is sad without one’s family. You don’t know why they separated you. The people that work there think you came alone here [to the United States], but it’s not so.

Even if detention centers create jobs and generate income for local governments and private corporations, detention has irreversible harmful effects on the mental health and well-being of immigrants, their families, and communities. Detention of immigrant children is not an isolated issue. It’s part of a system and infrastructure that daily affects thousands of children confined in detention spaces, exclusively for them, in 17 states of the U.S.

The impact and imprint left on children by immigration, deportation, family separation, imprisonment, or even the anti-immigrant narrative in the country, are unprecedented. With the separation of families, the U.S. government trusted it could dissuade people from immigrating, but, on the contrary, “the heavy-handed approach” has generated trauma and damages on the mental health of children and young adolescents, and immigrant communities.

Under the Trump administration, we find an oppressive political climate in the United States, with a furious anti-immigrant discourse and a punitive agenda. The infrastructure and machinery for the detention and imprisonment of immigrants have been reinforced and expanded through cruel measures to criminalize immigration. This reinforcement and expansion also separate fathers from their children, radically lowers the number of persons who are able to access asylum procedures and fosters massive and unprecedented incursions throughout the country and the militarization of the border.

BY THE NUMBERS: FAMILY SEPARATION

Children in Shelters before "Zero-tolerance."

Children Separated during "Zero-tolerance."

Children still Separated from Their Parents (2018)

Why Is it Important?

President Donald Trump’s “zero-tolerance” policies have terrorized the whole world by separating families when they cross the border. Although this is not a new problem, in recent years, family separation has become a tool favored by the US Government to deter migration. Family separation does not solve the underlying problems that lead families to migrate because many do it to escape violence, marginalization, and structural poverty caused by this system, which is currently in crisis.

What is the Situation?

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) identified the leading companies that benefited from family separation policies in 2018.

These firms build, operate, or provide services to facilities used for migrant detentions.

CoreCivic: Formerly known as Corrections Corporation of America, the country’s largest private prison company, owns and operates eight immigrant detention centers.

GEO Group: Company that operates private prisons and family detention centers around the world.

General Dynamics: One of the leading defense contractors. The company provides case management services in juvenile detention centers.

Some of the companies that finance these and other private prison and defense contracting firms:

- Black Rock

- JPMorgan Chase & Co

- Wells Fargo

How to Get Involved

Solidarity is part of our human nature, despite contrary institutional discourse. Reclaim it! Do not expect a solution from Governments because that will probably never happen.

Listen carefully to the voices of these boys and girls that call us to create more just worlds. Connect with the people who are building these safe spaces called sanctuaries.

notas al pie

-

Muldowney, Decca y Adriana Gallardo, “Zero Tolerance. About the Immigrant Children Shelter Map”, ProPublica, https://www.propublica.org/article/about-the-immigrant-children-shelter-map

-

El Acuerdo Judicial de Flores se llamó así en honor de Jenny Lisette Flores, inmigrante menor de edad que huyó de El Salvador en 1985 para reencontrarse con su familia en Estados Unidos. Es un precedente judicial que obliga al gobiernos de ese país a dar buen trato a niños inmigrantes y a detención en condiciones “menos restrictivas”, durante un periodo máximo de 20 días. En 2019, Donald Trump anunció que su gobierno pondría fin al Acuerdo Judicial de Flores en un intento de frenar la migración. Véase, Department of Homeland Security, DHS, “DHS and HHS Announce New Rule to Implement the Flores Settlement Agreement; Final Rule Published to Fulfill Obligations under Flores Settlement Agreement”, 21 de agosto de 2019,https://www.dhs.gov/news/2019/08/21/dhs-and-hhs-announce-new-rule-implement-flores-settlement-agreement

-

Cancino, Jorge, “Obama es el presidente que más ha deportado en los últimos 30 años”, Univision Noticias, 25 de agosto de 2016, https://www.univision.com/noticias/deportaciones/obama-es-el-presidente-que-mas-ha-deportado-en-los-ultimos-30-anos

-

US Department of Health & Human Services, “Office of Inspector General, Separated Children Placed in Office of Refugee Resettlement Care”, https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-BL-18-00511.pdf

-

John Burnett, Almost 15,000 Migrant Children Now Held at Nearly Full Shelters, NPR, 13 de diciembre de 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/12/13/676300525/almost-15-000-migrant-children-now-held-at-nearly-full-shelters

Referencias Infografía