PLAYING HIDE AND SEEK

the day-to-day life in the sanctuaries

Dulce, daniela y david

Dulce, daniela and david. 10-year-old Dulce, her 9-year-old sister Daniela, and her 4-year-old brother David have lived together with their mother since August 2017 and for over a year at Holyrood Church north of Manhattan in New York City.

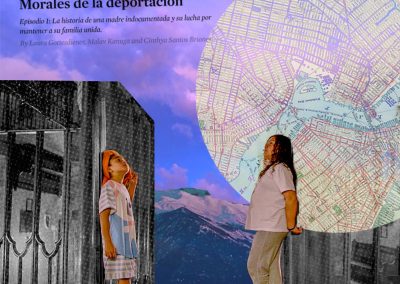

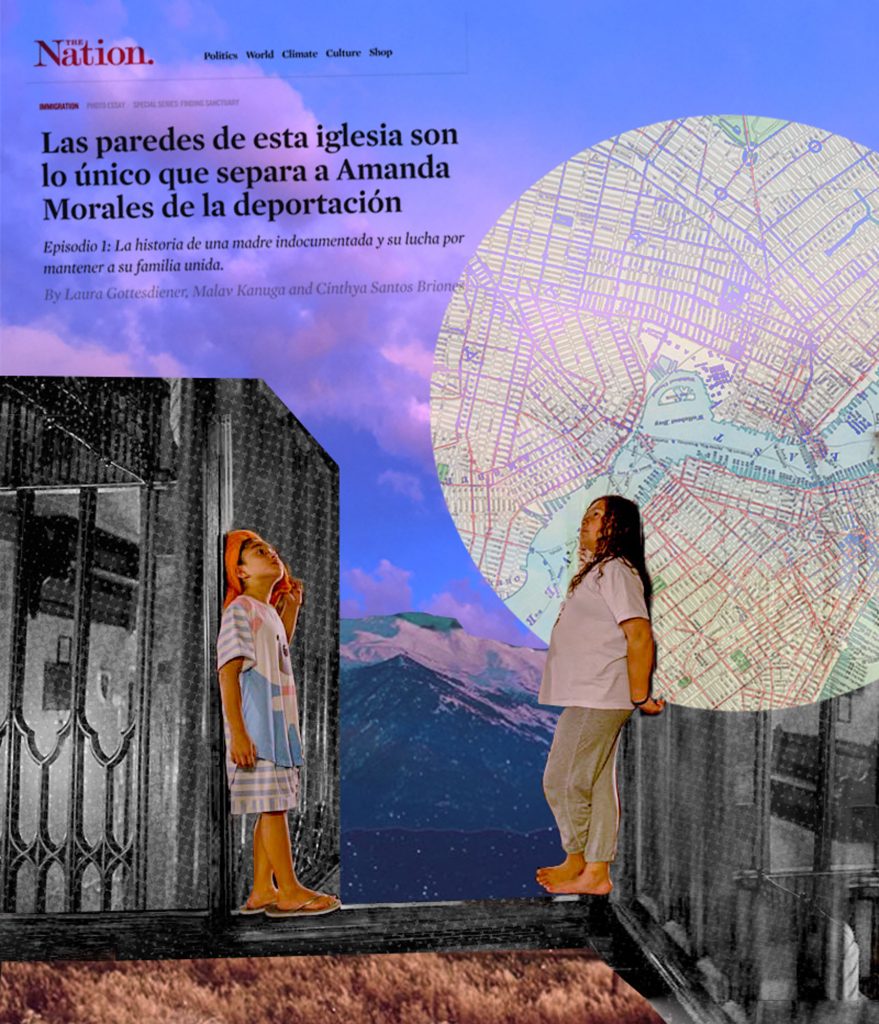

On August 2017, instead of appearing at the immigration offices with a ticket back to her native land, Guatemala, Amanda Morales Guerra, 33, decided to seek refuge with her three children—American citizens Dulce, Daniela, and David—in an Episcopal church in north Manhattan, in New York City. That was her response to the order of immigration authorities to leave the country, or else she would be deported and separated from her children. Amanda’s public action of seeking refuge is a visible acknowledgment of the devastating decisions immigrants must make daily in the United States.

In response to the current immigration crisis in the United States and anti-immigration policies put in place by the Trump administration, congregations of different religions began offering physical shelter, protection, moral support, legal support, and solidarity to undocumented immigrants with final orders of deportation. This resistance strategy against anti-immigrant policies relies on religious or faith institutions dates to 1980. It started with the creation of the “Sanctuary Movement,” when hundreds of churches and synagogues converted their temples into a “sanctuary,” as an open civil disobedience action, to give shelter to Central American migrants fleeing from the civil war in their countries. In 2007, as a direct response to an increase in deportations during the George W. Bush and the Barack Obama administrations, the “New Sanctuary Movement” was conceived. Data from the religious organization Church World Service indicate that during President Donald Trump’s Administration, the number of cases of immigrants who have decided to “take sanctuary” (as it is commonly referred to) together with their families has increased. Today more than 50 congregations in the United States give shelter to immigrants and their families at risk of deportation.

The process of seeking refuge in a church or “take sanctuary” and resistance to deportation begins when an undocumented person who is allowed to reside legally in the United States has been sentenced by an immigration court to return to his or her country of origin. That is why he or she decides to seek refuge in a temple.

The process ends when deportation is suspended without risk of arrest. Since there is no specific time framework for shelter in a sanctuary, the person can remain for periods from a few weeks to months, even years. It’s a sort of “house arrest.”

The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) considers churches (also schools and hospitals) as “sensitive places,” and people who seek refuge in temples as “fugitives” and “criminals.” For this reason, they are at risk of being deported at any time. While people at risk of deportation are fathers or mothers of children and adolescents, the whole family undergoes this complicated process to avoid being deported and fight against family separation. Dulce, Amanda’s eldest daughter, 10, her sister Daniela, 9, and David, 4, have lived with their mother for more than a year in the Holyrood Church, hoping to keep living together and that their mother successfully avoids deportation and gains “legal” status.

Their lives changed when their mother told them that for not having “U.S. documents,” she must return to her country, though she had the choice of seeking refuge in a church to avoid this. Dulce often listened to her parent’s conversations

“Since I’m the oldest, I knew my mother was being deported because my parents spoke all the time of what they would do. Then, my mother brought us to this church.”

The day Amanda had to leave the country, a group of faith leaders, activists, politicians, and members of the Sanctuary Movement coalition organized a press conference announcing to the media their solidarity and support to Amanda and her children. It was the first time that Dulce and Daniela were on T.V. and were interviewed by a dozen journalists who repeatedly asked them how they felt and were they scared to lose their mom, or that their mom would be deported.

Dulce felt intimidated. She didn’t know what to say and didn’t want to be in front of so many cameras with strange people. However, she hoped that by giving interviews and making more visible their situation, they would help stop her mother’s deportation. It was the first family to seek refuge in a church in New York City in President Donald Trump’s Administration. Thus, the news became widely-known and spread globally.

Overnight, Dulce, Daniela, and David had to leave their home, school, friends, family, and the community to move into the church with their mother. The church is two hours away from the home where they grew up and lived all their life, in Long Island. They left the house with a couple of changes of clothes and some toys. They had to leave behind their chicks—they took care of them as pets—and the “fun” memories of Summer in the plastic pool their father bought them. Dulce and Daniela could not say goodbye to their school friends. They were ashamed to tell them about the situation the family was going through. They didn’t want their friends to know that the “migra” [immigration authorities]—an organization that’s mistaken for the police or the FBI—were looking for mom.” Their father had to stay home, and he couldn’t move with them, given the risk of losing his job. In the end, their family would be separated.

When they arrived at the church, Amanda and her children lodged in a small library that members of the congregation and father Luis Barros had set up as a dormitory. Only two bunk beds and a small table to eat fit in there. It wasn’t too comfortable a space, but Amanda kept reminding Dulce and Daniela at all times that they would only live there temporarily, while their situation was made right. In this regard, Dulce mentions:

“It surprised me that the church was quite big and somewhat scary. The women that worked there showed me the room where we would stay. We were happy, but when the time came for my dad to leave, I started crying because I would miss him. Because I feel emotional easily, and I was sensitive. I cried a lot, but the women in the church told me not to cry, that everything would be alright. So, I calmed down, and I said goodbye to my dad. I was very sad. When we went to bed, we were scared, but mostly me, because I really missed my dad and cried, and cried. I wanted to be home again with my dad.”

Daily life at the church goes on while Amanda awaits good news from her lawyer. She has enrolled Dulce and Daniela in a new school near the church, a bilingual primary. They like the new school because they have learned how to swim, and they have skating classes. In the afternoon, they take art classes at the Washington Heights Choir School, a program part of the church where they live. There they learn to sing, play the piano and other instruments. They have found new friends, and at times they can forget their troubles. The girls have taken over the church as if it were their own home. In the back patio, they jump rope, play soccer and hide-and-seek.

Every morning, Dulce y Daniela get ready for school. They have witnessed the seasons pass; summer has left, it’s snowing. Amanda heats sandwiches for them in the microwave and prepares a Nesquik drink.

—Dulce asks her mom, “When will we go back home? I awfully miss having breakfast with freshly made tortillas. I miss the chicks a lot.”

“The chicks are no longer there,” she answers. “Because it’s freezing. Besides, I don’t know; I’m waiting for the lawyer to tell me something. The court sent me the documents to seek asylum. Hurry up. We must leave for school”.

“I don’t want to go. I’m scared. What if the police [ICE] comes for you, mom?”

“They can’t come in here,” Dulce answers.

Dulce and Daniela grab their backpacks as their mother walks with them to the church door to say goodbye.

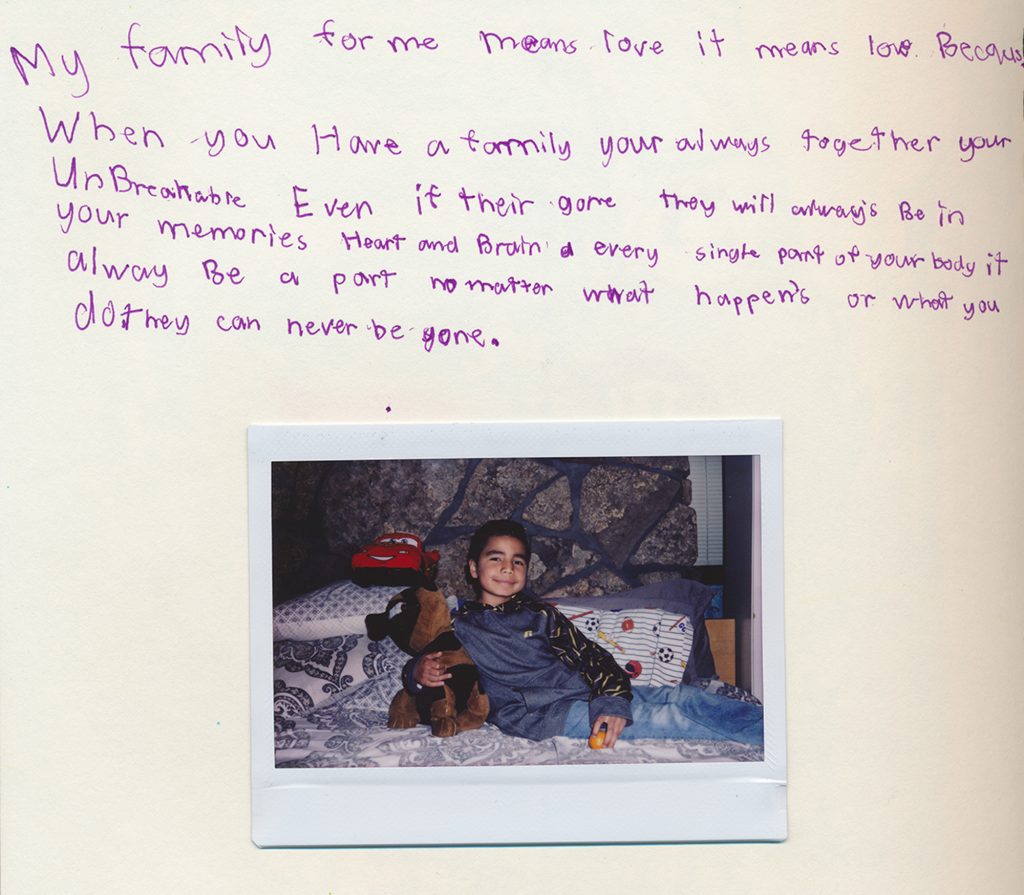

For Dulce and Daniela, it’s been a drastic change to live in a church, away from their family environment, their community, and friends. But what does it mean for these children and adolescents to live like refugees in a church? How do they understand the economic and political implications that moved their parents to emigrate to the United States? For them, what does it mean to be a refugee?

Often Dulce and Daniela say they are refugees, but, in contrast with their mother, they can go out of the church without the risk of being arrested by the “police” because “they have U.S. documents and cannot be deported.”

It’s a common thing for the feelings of fathers and mothers that live as refugees in churches to become collective. The kids feel the same anxiety the parents feel; they know that something is not right. This situation generates the feeling that being an immigrant in their country “is not good,” that “having crossed the border without any documents illegally” is a crime. Dulce and Daniela know that because they are citizens, they have “more rights than their parents.” They have the right “to be free.”

“When you don’t have documents in the U.S., it is very dangerous,” says Daniela. “You have to hide.”

There are some cases of boys and girls who cannot live as refugees in the church with their dad or mom. Either because the church is too far from school or there is minimal available space. Kevin, 10, is one of these cases. He visits his mother and sister—Sofía, 3—every weekend in a church in Manhattan, New York. According to Kevin, he “is not a refugee because he only visits his mother on weekends.”. Kevin, as well as Dulce and Daniela, link and understand the term “refugee” with “protected,” “being safe.” They know that in church, their mothers will be protected, and for this reason, they took refuge there. Also, they are aware that it is a space that helps migrant families like theirs because “the migra can’t get in.”

Furthermore, they recognize that their parents have come from far away for economic reasons, fleeing from violence and poverty, overcoming many obstacles and borders. Their mother has told them the reasons that brought them to this country. The story of why they crossed “without documents” becomes part of the oral history and collective memory of children’s family and community environment.

—”My mom cannot return to Guatemala,” Dulce tells her sister Daniela. “Because it’s very dangerous. She came to New York because of this, so we were born here and had a better life.”

Bryant Moya, 10, is a refugee in a church with his younger brother, 3. Their mother, Ingrid Escalada, a native of Perú, has been living in a church in Boulder, Colorado for two years. Just as Dulce and Daniela, they had to leave their home, school, family, and community. Bryant has lived in three different churches in Colorado. The reopening of his mother’s court case has been difficult because she was convicted of a class C felony for criminal impersonation.

—“My mom needs a big pardon to be able to get out of the church,” explains Bryant.

He spends his life in sanctuary between school, piano lessons, and soccer. Every day his mother wakes up early to fix him breakfast and watches him walk to school from the back door of the church. Bryant likes school a lot, and, above all, math. He wants to be an engineer when he grows up to repair cars and give his mom a better life. In school, he is quiet, shy, and introverted. He doesn’t talk much with his classmates about his family’s situation, “it hurts him speak about it.” And even when his schoolmates ask him why he lives in a church, he doesn’t explain.

—”I don’t say why I’m living here. I don’t want my friends to feel sad for me, just for because of a president and his rules”.

The truth is that for children and their families, it is difficult to adapt to the life of a refugee in a church. Generally, the spaces are small, improvised, and allow little privacy.

—”You’re rarely alone. There are always many persons, and they upset you. It’s not that easy because if you live in a church, there is a complicated reason you don’t want to tell, and it hurts to say you’re living here and what’s happening to your family. Also, it’s something that shouldn’t happen, and it’s not right.” Bryant remarks.

There are some cases of boys and girls who cannot live as refugees in the church with their dad or mom. Either because the church is too far from school or there is minimal available space. Kevin, 10, is one of these cases. He visits his mother and sister—Sofía, 3—every weekend in a church in Manhattan, New York. According to Kevin, he “is not a refugee because he only visits his mother on weekends.”. Kevin, as well as Dulce and Daniela, link and understand the term “refugee” with “protected,” “being safe.” They know that in church, their mothers will be protected, and for this reason, they took refuge there. Also, they are aware that it is a space that helps migrant families like theirs because “the migra can’t get in.”

Furthermore, they recognize that their parents have come from far away for economic reasons, fleeing from violence and poverty, overcoming many obstacles and borders. Their mother has told them the reasons that brought them to this country. The story of why they crossed “without documents” becomes part of the oral history and collective memory of children’s family and community environment.

“My mom cannot return to Guatemala,” Dulce tells her sister Daniela. “Because it’s very dangerous. She came to New York because of this, so we were born here and had a better life.”

Bryant Moya, 10, is a refugee in a church with his younger brother, 3. Their mother, Ingrid Escalada, a native of Perú, has been living in a church in Boulder, Colorado for two years. Just as Dulce and Daniela, they had to leave their home, school, family, and community. Bryant has lived in three different churches in Colorado. The reopening of his mother’s court case has been difficult because she was convicted of a class C felony for criminal impersonation.

—”My mom needs a big pardon to be able to get out of the church,” explains Bryant.

He spends his life in sanctuary between school, piano lessons, and soccer. Every day his mother wakes up early to fix him breakfast and watches him walk to school from the back door of the church. Bryant likes school a lot, and, above all, math. He wants to be an engineer when he grows up to repair cars and give his mom a better life. In school, he is quiet, shy, and introverted. He doesn’t talk much with his classmates about his family’s situation, “it hurts him speak about it.” And even when his schoolmates ask him why he lives in a church, he doesn’t explain.

—”I don’t say why I’m living here. I don’t want my friends to feel sad for me, just for because of a president and his rules”.

The truth is that for children and their families, it is difficult to adapt to the life of a refugee in a church. Generally, the spaces are small, improvised, and allow little privacy.

—”You’re rarely alone. There are always many persons, and they upset you. It’s not that easy because if you live in a church, there is a complicated reason you don’t want to tell, and it hurts to say you’re living here and what’s happening to your family. Also, it’s something that shouldn’t happen, and it’s not right.” Bryant remarks.

Bryant enjoys spending time with his brother Aníbal and teaching him how to play video games. Living in a church has also positively changed his way of thinking. The solidarity expressed by people surprises him, particularly how theygive their support without knowing him or his family. The parishioners of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Boulder, where they, have organized to provide Bryant and his family financial and moral help. Organizations such as Metro Denver Sanctuary Coalition and SIRC provide legal support. Activists and pro-immigrant organizations support them in various campaigns to join efforts so that Bryant’s mother can leave the church without fear of deportation. A group of volunteers called DoorKeepers watches the entrance door to the church for better control of the family visitors and to prevent immigration agents from entering.

What are the emotional and psychosocial consequences of living in fear of your mother or father being deported? How does it change children’s ludic perception?

For Bryant, his childhood has been “altered” since his mother took refuge in the church.

Here [in the church], I feel protected, but I’m not happy like other kids. I’m a kid who’s not too happy being with his family. And I feel safe because all the people are protecting us. People from everywhere live here. It doesn’t matter if they come from far away; they take care of us.

One night I was dreaming I had lost my mommy, that “ICE” grabbed her and after that, I couldn’t see her for the rest of my life. After, when I woke up, I didn’t want that to happen. “

To the question of how their childhoods and lives changed since living in church Dulce, Daniela, Bryant, Kevin, and other children, their answer was the same: “I am not as happy as I was before.”

There is a shared narrative and feeling these children voice about not having fun the same way they did before their mothers took refuge in a church. They now say they are more frightened and more “alert.”

For Edwin—a 14-year-old adolescent born in Colorado—, from the time his mother is fighting not to get deported, he has had to pause his childhood.

—”Since my mother was at risk of deportation and took refuge in the church, our lives have changed a lot. We have to be on the alert most of the time to see if there’s anything suspicious, something different. We must be alert in case “Immigration” is there, and we must know what to do because they can take my mother from away from us,” Edwin says.

While these children make new friends and receive gifts from volunteers and members of the congregations that express solidarity with their families, they feel “displaced.” Childhood as a possibility of creation, of playfulness, of encountering the unknown, and curiosity, is transformed and sometimes dilutes with the most opposite feelings like anxiousness and fear. Nevertheless, there is laughter and games in the churches. These children communicate that they feel wanted, loved, and supported. “People” bring them presents. At times, they feel happy, and they find themselves again in their world of fantasy where everything is possible.

Besides, children have voiced feeling sad that their mother or father can’t leave the church. For Bryant, living in refuge in the church is “technically like living in a jail.”

“I can go out because I was born here [in the United States], but my mother can’t because ICE will deport her, and then we won’t be able to be together like a normal family.”

These children’s mothers have spoken about how their sons and daughters experience anxiety and fear of leaving the church without them.

—“Before they didn’t feel this fear like that of going to school. They think that when they come back, they won’t find me here,” explains Amanda.

Since Donald Trump took office as President of the United States in January 2017, any immigrant living “illegally” in the country is subject to deportation. More than 97 000 immigrants who lived undocumented in the United States were detained during the first eight months of 2017. During this Administration, there has been a 43% increase in detentions compared to 2016, according to data from ICE. Consequently, many families are being separated and forced into deportation, and this means they must leave their children behind or become fugitives. Amanda’s radical and defiant decision to seek refuge has brought hope to many fathers and mothers who confront and challenge immigration laws.

SANCTUARY MOVEMENT

What is the Sanctuary Movement?

It is a coalition of churches, synagogues and places of worship that provide shelter, legal support and media attention to people who decide to take refuge in their temples.

When did the movement start?

El Movimiento Santuario nació en la época de los 80’s en Tucson Arizon cuando el gobierno estadounidense apoyó a gobiernos dictatoriales en Centroamérica pero rechazó asilo político a un grupo de 13 migrantes salvadoreños que corrían riesgo de ser asesinados por un escuadrón de la muerte. Esta acción provocó que decenas de Iglesias y lugares de adoración decidieran albergar migrantes centroamericanos que huían de las guerras civiles.

Is there a new sanctuary movement?

El movimiento resurgió en 2007 en el gobierno de George Bush como respuesta a una ley anti-inmigrantes y de nuevo en el gobierno de Obama después de que los hospitales, las escuelas y los lugares de adoración fueran considerados lugares sensibles para la entrada de ICE.

How many sanctuary churches are there?

Después de las elecciones del 2016 el número de iglesias santuarios se duplicó de 400 a 800. En enero del 2018 se reportaron 1,100 congregaciones parte del Movimiento Santuario.

What does it mean to "take sanctuary"?

Personas que cuentan con órdenes de deportación y deciden tomar asilo en iglesias que son parte del Movimiento Santuario.

How long does this process take?

El proceso de Santuario comienza cuando una persona sin documentos para residir en Estados Unidos es sentenciada por una corte migratoria para retornar a su país y termina cuando la orden de deportación es suspendida sin orden de arresto. Puede durar desde unas semanas hasta años.

How many people on average decide to take sanctuary?

En 2017, 37 personas tomaron Santuario y 9 pudieron salir con una especie de indulto.

En 2018 se reportaron 26 ciudades con iglesias Santuario,y hasta este año 36 personas se encuentran refugiadas en santuarios de manera pública; se formaron 40 coaliciones o redes de apoyo.

What is the criminalization of refugees?

Las personas que se han refugiado en templos son catalogados por ICE como fugitivos y criminales, por lo que están en riesgo de ser arrestados en cualquier momento.

Does Trump promote anti-migrant policies?

El presidente de Estados Unidos ha firmado varias órdenes ejecutivas relacionadas con la inmigración y ha terminado y limitado la protección que algunos inmigrantes recibían en administraciones pasadas (DACA, TPS).

1, 2, 3 FOR ME AND FOR MY FAMILY

Childhood: Decision-Making Capacity and Political Action

“When I was a girl, I remember being very happy. I often played in my grandparents’ town. I climbed up trees. I didn’t have any worries. During childhood, life was enjoyable. Now I see how my children have grown with fear that one day their mom will be deported. And I also see how different childhood is when you live in fear,”

–says Jeanette Vizguerra, an undocumented mother, and one of the most prominent activists of the immigrant justice movement in the United States, founder of the Metro Denver Sanctuary Coalition in Colorado.

Her children, Luna, 14, Roberto, 12, and Zury, 7, have grown accustomed since they were very young to accompany their mother in her process to avoid deportation.

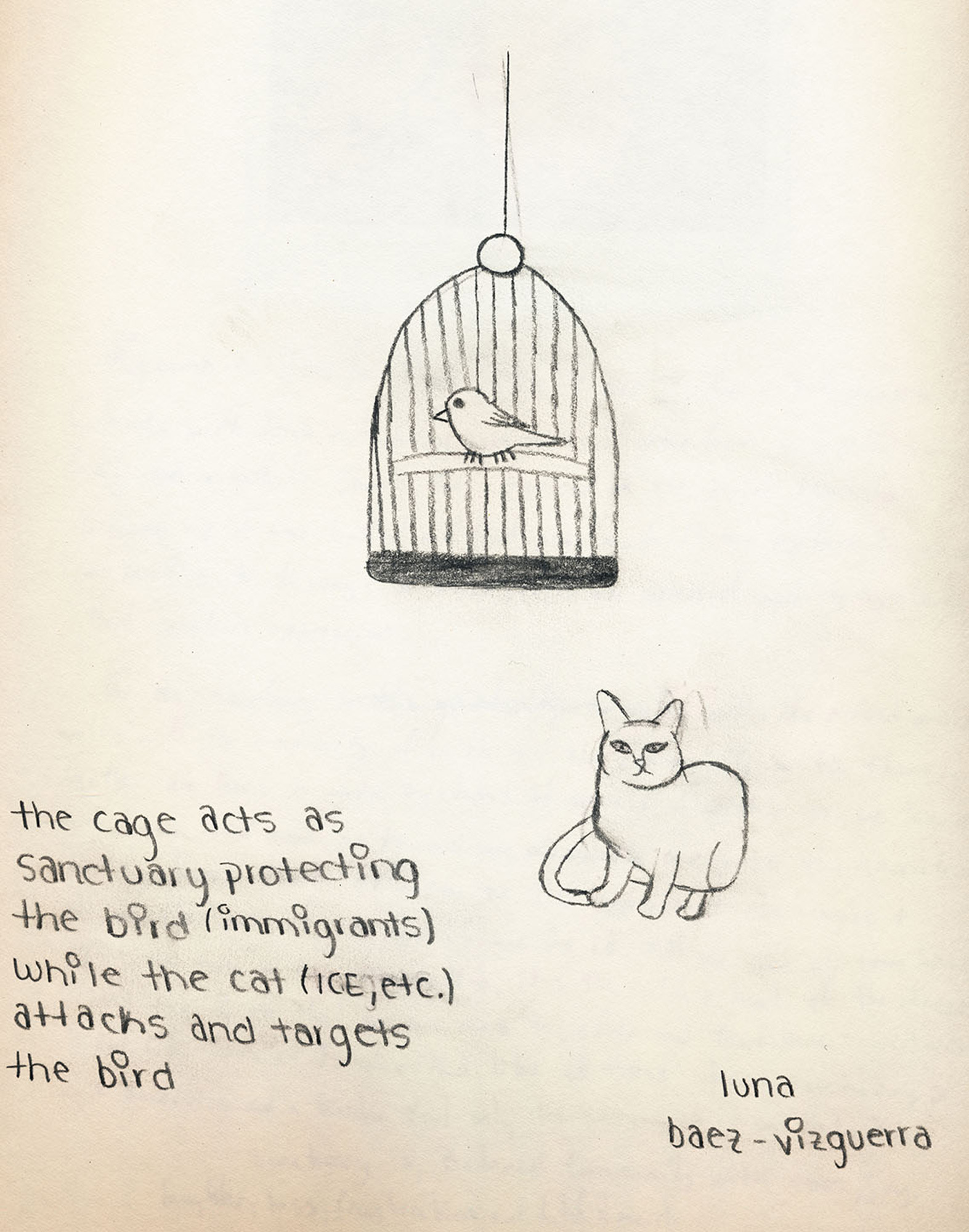

Jeanette and her children have taken sanctuary three times in different churches in Denver, Colorado, for risk of deportation. Luna, a charismatic adolescent and school leader in her high school, has learned from her mother to speak about anti-immigrant policies, deportation, and her right as an American citizen to keep her family together.

Since she was a very young child, she has been a spokesperson and “political representative” for her mother and her family. She is very proud that her mother has been considered by Time magazine as one of the most influential people of 2017. Luna remembers how, from a tender age, she accompanied her mother to rallies, protests, and to organize the undocumented community concerning their labor and legal rights.

“Since I was a girl, I knew that my parents didn’t have any documents. They weren’t like me and did not enjoy that privilege because they weren’t citizens”. “I’m not like other girls my age. I had to mature soon, be alert, fight for my family,” mentioned Luna while her sister Zury, 7, listens in, and adds,

“My mom is a tenacious lady, and we fight with her.”

On the refrigerator in the kitchen of Luna’s home, there’s a piece of paper that reads: “Rapid response.”

—“What’s that paper for, Luna?” I asked.

“Names of lawyers, activists, and priests. We have them stuck there in case ICE comes for my mother. That way, we can talk to those people to mobilize the community and soon let people know that ICE is in my house. My mother has taught my siblings and me since we were young kids to be alert. She has also trained us on what to do in case she is detained by immigration agents.

Luna and her brother Roberto, whom they affectionately call Gallo, have gone to the Capitol in Washington with Bryant, the oldest son of Ingrid Escalada, to engage in protests and give visibility to “family separation and deportation.”

“Compared to my sister Luna, I’m not much of an activist. She is a leader, even in school. She gets it from my mom,” mentions Gallo. “We go to Washington to demand that the Government does not separate us from our mothers because we have that right as citizens of this country.”

They have also trained other children, like Edwin, on immigrant rights and “quick response.”

—”My mom has trained me to know what to do in case ICE enters my house and arrest her. We have a list of people to call, like pastor Shana. For example, if immigration agents are outside my house, we mustn’t open. I have to ask them in English to show me a deportation order. Take a picture and send it to my mother’s lawyer to see if it’s real—he explains.

Edwin’s mother, Sandra López, took refuge for nine months in the Two Rivers Unitarian Universalist church, in a town surrounded by mountains in Carbondale, Colorado. Edwin and his family live about 45 minutes away from Carbondale, in Silt. When his mother received her final deportation order, the pastor’s Shana congregation offered them to “take sanctuary” in the church.

—”It was very tough because, during the time my mother lived in the church, I couldn’t stay with her because my school was far away. I don’t agree with what this Government is doing to immigrants like my mom. I’m not a normal kid like my school friends, who can go out without fear. I’m always thinking about my mom; if she’s OK, if ICE won’t arrest her.

However, as the sense of childhood fades, kids assume the role of political representatives and spokespersons for their undocumented mothers or fathers. Being bilingual helps them to speak in public about their right as American citizens to have their family together. They have become the critical mass of this system.

In March 2018, Daniel Hernández, 10, wrote a letter to Thomas R. Decker—head of New York immigration police. In the letter, he requested him to stop the deportation order against her mother, Aura Hernández, who had taken sanctuary in the Fourth Universalist Society church in Manhattan. He spoke to the public in the media, and though he wasn’t very fond of doing that, he felt it was his duty to claim his right to live with his united family. Since then, Daniel has attended several press conferences, public protests and rallies as spoke person for his family.

Mr. Thomas Decker, I’m here because I want my mother to come back home with my family and me. This year I felt a lot of sadness because my mother was not with me. I feel very sad when I leave my mother. If I were without my mother, I would be very sad. Living in a church is not very easy. Sometimes we have to be in a small room so as to not make a lot of noise. I’m scared. When I sleep at home, I think that they might arrest my mother. They could send her to Guatemala. I also want my sister to be with me because I love her a lot. In school, I get distracted thinking about my mother.

Letter from Daniel Hernández a Thomas R. Decker

A few days before they took refuge in the church and their case became public in the media, in the middle of a class, Daniel asked permission from his teacher to make an announcement to his classmates.

—”Maybe you will see me tomorrow on T.V. supporting my mom. ICE wants to get my mother out of the country, and I’m going to support her”.

And though Daniel has conducted himself as a firm political representative against his mom’s deportation, after they took refuge in the church, he started experiencing panic attacks, fright, and distress.

—”He’s even afraid of going to the toilet. He won’t leave my side for a moment. He’s afraid ICE will come looking for us,” his mother Aura says. “It’s difficult for a child to understand this process. After all, they’re only children. He shouldn’t have to stand up for me.

Daniel, Dulce, and Daniela went to a symposium held at the Tabernacle Synagogue, in Washington Heights, about immigration, sanctuary, and deportation. They spoke to an audience of at least 150 people about the situation their families were going through.

Dulce and Daniela took the microphone while holding banners that read “Stop separating families” and, in a mellow and shy voice, highlighted the need to return home together with their mother and that she “could come out of the sanctuary” without fearing deportation.

On Mother’s Day, May 10, Aura and her son Daniel together with religious leaders, activists, and members of civil society, organized a march against family separation and in support of mothers living in sanctuary in the church. Daniel, his cousins, and other children from the community headed the procession chanting slogans. “No human being is illegal” and “Don’t separate families.”

Austin sanctuary network

Austin

New sanctuary coalition

Nueva York

New Sanctuary Coalition está dirigida por y para inmigrantes para detener el inhumano sistema de deportaciones y detenciones en los EE. UU.

Iowa sanctuary movement

Iowa

Movimiento del santuario de Iowa: un llamado a la acción moral, incluido el santuario, por las casas de culto de Iowa

The fact is that the experience of living sheltered in a church and accompanying their mother or father in the movement against deportation has politicized these children and allowed them to acquire knowledge on legal aspects and the social justice movement.

At the same time, other children and adolescents have decided to raise their voices against anti-immigrant policies. Some of them have undocumented parents, others are undocumented themselves or have grown in a family where one of the parents is deported. What has been the impact of this culture and the anti-immigrant policies psychologically and socially on this stage of children’s emotional development, as well as on the behavior of children and adolescents living sheltered in a sanctuary? How have socially assigned understandings and knowledge become transfroemd, because, during childhood, they were required to understand legal notions and political processes such as the consequences of their mother or father being “illegal”? How do they redefine and take ownership of concepts such as “deportation,” “imprisonment,” “refuge,” “fugitive,” “citizen,” “immigration,” “border,” “asylum,” and so on?

Furthermore, undocumented mothers and fathers began developing a series of plans and measures of rapid response because of this anti-immigrant policy and culture under President Donald Trump’s Administration, and with the increase of arrests and deportations of immigrants across the country. Through a rapid response, mothers can grant custodial power over their sons and daughters to a relative, a compadre—the godfather of one’s child or father of one’s godchild —, or a friend, in case of deportation.

As the detention and deportation of immigrants increases in the United States, many undocumented immigrants prefer to keep living anonymously to avoid detection. Others are detained and subjected to dehumanizing procedures, resulting in detention and separation of families and communities before deportation. In turn, other immigrants decide to make visible their deportation cases and fight for the right to remain in the United States while publicly “taking sanctuary,” protected by a church or a congregation of faith.

Under President Donald Trump’s Administration, anti-immigrant and xenophobe discourse has become exacerbated in the United States, placing emphasis on criminalizing immigration. This current political climate has had a powerful impact on the way people experience childhood and how it is perceived, not only by children sheltered in sanctuary churches but also among kids with undocumented migrant parents and migrant children separated from their parents when crossing the border.

Santuarios en números

Santuarios en Estados Unidos

Ciudades con santuarios

Redes de Solidaridad

Why is this relevant?

In a world in constant crisis, caused by political, economic and environmental conflicts, the migration of people and entire communities is a present reality. The tendency on the part of governments is to close borders, build walls, discriminate and criminalize, separate ourselves between people. The gravity of the circumstance is not a game, but the girls and boys who have to face this structural inequality are not alone. The sanctuary movement is a light in the midst of darkness. It shows that it is possible to create spaces of solidarity that break with the logic of fear and separation. It shows that the solution to hate speech is organization and empathy between people, regardless of origin, skin color or social class.

What is the situation?

Hate speech and xenophobia are on the rise, promoted by irresponsible politicians and reproduced by the mass media. This translates into the construction of a narrative of separation and the construction of the image of the migrant as danger. This justifies racist and exclusionary policies that have a direct impact on the lives of millions of families.

How can you support?

Solidarity is part of our humanity and not of an institutional discourse, recover it. Do not expect the solution to come from governments because it may never come. Listen carefully to the voice of these girls and boys who are calling us to create more just worlds. Connect with those people who are building these safe spaces called Sanctuaries.