Jumping over the Wall, Crossing the Border:

“If they Catch Me Today, I’ll Come Back Tomorrow.”

A young man is in search of a dream. To get everything he has ever wanted. “May I lack no money, food, or a home.”

Every year, thousands of Mexican adolescents are driven out of their home communities and cities because of inequality, poverty, lack of jobs, and the failure of education as an engine for social mobility. The reasons why these adolescents flee are often the growing violence and the expansion of the activities of drug-trafficking cartels. Public institutions and policies—that don’t appreciate the relevance of their contributions to social and economic life, and community development—motivate them to leave. Driven by urgent needs and seeking a different future and livelihood possibilities, many Mexican adolescents and youths will try crossing the border, on their own or accompanied, before coming of age.

They leave the country tired of looking for alternatives that never materialize. They leave behind precarious jobs that don’t offer chances of bettering their livelihood conditions or an opportunity to attain upward social mobility. Many already have children, and others go in search of their parents or siblings who left long ago, wanting to meet with them again and reunite with their family. They are adolescents connected through the internet and social media. They aspire to the living standards of the American Dream and the consumerist aspirations of the global middle class. For them, life is in turmoil, and the vital energy that drives them doesn’t cease, won’t wait or stop.

Some, almost always male, come from environments marked by marginalization and poverty. Others come from “tough” neighborhoods ruled by “the mafia.” They are recruited there to traffic drugs and human beings. This strategy is critical for the drug cartels to move drugs across the border, knowing full well that since they’re minors, in case of detention, they will be freed immediately, and can return to their activities after deportation. Some have crossed the border several times with drug shipments, coordinating transport and delivery, or guiding groups of people through the desert. They act as wall “brincadores” (jumpers), as “halcones” (lookouts) or play the role of any other echelon of the various parts of the complex and well-organized division of labor that makes up human trafficking across the wall.

For many adolescents, working as a “burrero” (carrier) hauling drug shipments, is a valuable alternative when there are not enough financial resources to pay a “coyote” (immigrant smuggler). This activity offers safety, guidance, food, and water that cartels give them during the multiple-day journey through the desert. Some even receive payment at the end of the crossing and when handing the shipment.

What follows is an account that shows how migration stops being an extraordinary and disrupting event in everyday life. Migration is no longer out of the ordinary when a person spends years imagining the possibility of a different life and has tried crossing the border many times. Tirar pal’ norte (travel north), migrate, cross the desert, cross to the “other side,” jump the wall, cross the “line” becomes the driver, and course of a new everyday reality. Deportation and recurrent comebacks to the home community become a part of constant personal development and personal history. Detention and deportation mean that the desire to reach “the other side” is not yet realized. Realization is postponed: it becomes more complicated. The road becomes longer and more difficult than expected. Sometimes deportation and returning to the home community are opportunities to rethink strategy and gather new resources.

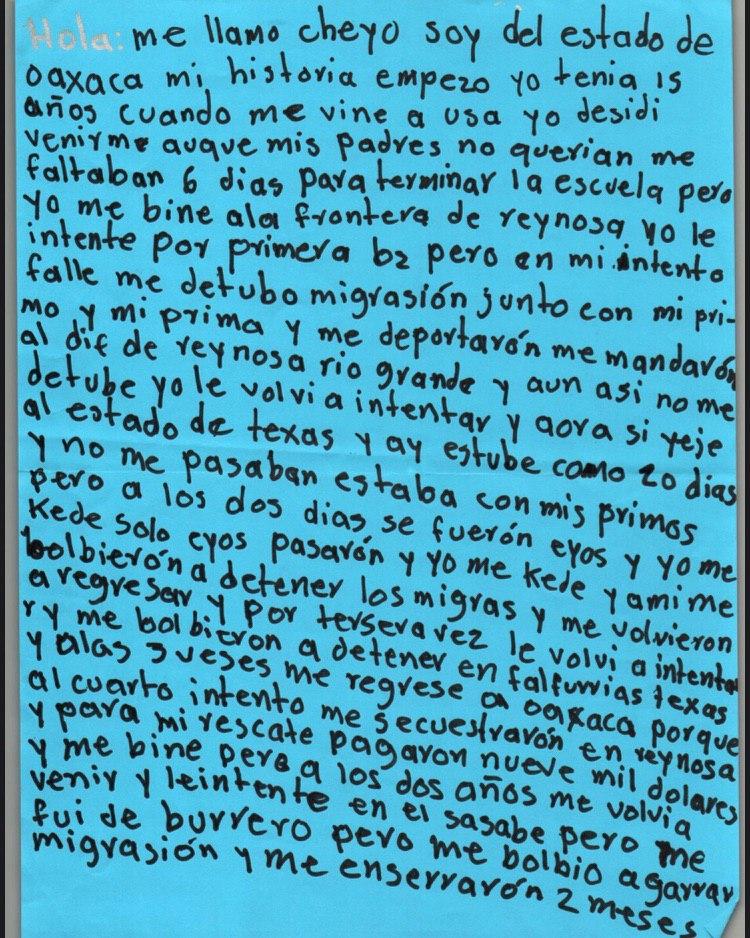

Cheyo’s Story

“I’ve tried five times, but despite everything, I don’t give up.”

Hi, my name’s Cheyo, and I’m from the State of Oaxaca. My story began [when] I was fifteen when I came to live in the United States I decided to come, though my parents didn’t want me to. I had six days to the end of the school, but I went to the border at Reynosa. I tried for the first time, but I failed. Immigration stopped me and my cousins—a boy and a girl. I was deported. They sent me to the DIF in Reynosa, Grande River, and still, I did not quit. I tried it again. This time I reached the state of Texas. I was there for about 20 days, and they did not make me cross. I was with my cousins, but after two days they left, and I was left alone. They crossed, and I stayed, and the migras (immigration authorities) stopped me again and returned me once more. I tried again for the third time, and the three times I went back to Oaxaca because, on the fourth time, I was kidnapped in Reynosa. They paid nine-thousand dollars for my ransom. I came to Oaxaca, but after two years I tried in Sásabe. I went as a burrero. But immigration authorities caught me again. I was locked-up for two months, and then they deported me.

Again, I came back to Oaxaca, but I was put back in the DIF. There I waited for my transfer and left. Two months later, I went back again. Once more as a burrero. But after walking for five days we were out of food and water; I couldn’t stand it any longer. They left me in the desert but warned me that I’d better die. Otherwise, they’d do it here in Mexico. I gave myself up to the immigration authorities. They apprehended me and deported me again. I’ve tried five times and can’t get there, but I will keep trying until I cross.

To my fellow Oaxacans: don’t chicken out, we’re powerful. Cheer up. Life goes on! Long live, Oaxaca! My story is real. Cheer up, my fellow countrymen!

During the last decade, the number of unaccompanied Mexican minors—not in the company of an adult who can prove a direct family tie— detained at the Mexico-US border limits by the Border Patrol has been as high as that of children and adolescents from countries of the so-called Northern Triangle of Central America (El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala). However, an in-depth analysis reveals that, in the case of unaccompanied Mexican adolescents, predominantly male, only 24% are detained for the first time. At the same time, the rest are apprehended on many occasions, including 15% at least six times while crossing the border.

The geographic proximity and cultural drive toward migration to the United States make it so that multiple attempts to cross the border are “easier” or more attractive for Mexican adolescents. But this is not the only factor explaining the great number of deportations they have experienced. Another element to take into account is a U.S. law passed in 2008. This law looks to prevent human trafficking. There is also a bilateral agreement signed with the Mexican government to grant differential treatment to Mexicans, who are returned a few hours after detention, and many times without activating mechanisms to identify if they are victims of forced recruitment or of human trafficking. As a result, 95% of unaccompanied Mexican minors are deported immediately after detention. According to 2014 numbers, around 97% were adolescents. Among them, only 8% were women.

The quickness of the procedure, the negligence and violation of due process by U.S. immigration authorities during detention, and deportation have meant that thousands of adolescents that are recruited by drug traffickers and forced to smuggle drugs through the border cannot denounce their situation or seek international protection in the United States. On the Mexican side, the result of the lack of research on the subject and negligence of the matter from institutions specializing in child and adolescent protection is that the problem remains invisible and keeps occurring.

Two-thirds of unaccompanied Mexican adolescents detained at the border with the United States come from border states, primarily from Sonora and Tamaulipas. They also come from states in the southern part of Mexico with the highest poverty rates: Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Guerrero; plus, those states with the largest presence of drug trafficking cartels: Michoacán, Sinaloa, and Veracruz.

Like the Tigres del Norte song says: “If they catch me today, I’ll come back tomorrow. And if they capture me, I’ll be back the day after tomorrow.”

Sometimes, to be detained and returned to their home communities allows adolescents to develop relationships and strategies that, far from interrupting or cutting short their travels to the United States, opens up the possibility to continue through new routes. During their stay in the Border Patrol’s “iceboxes” and in government shelters where they are kept safe in Mexico after deportation, male and female adolescents from the center and south of the country find each other along with their new northern peers. They also develop ties of friendship, solidarity, exchange, and negotiation, allowing them to try, once more, to cross the border. They exchange advice, strategies, and knowledge about migration and how to cross the border. They form solidarity agreements to help each other once detention or sheltering periods are over, and they also establish financial contracts, so the more experienced act as guides or “coyotes” of those willing to try again. These meetings enable those who lack expert knowledge, to change their strategies in planning new crossings, based on bonds of support, exchange, and negotiation built during the journey.

Immigrant detention, sheltering, deportation, return, and other processes that prevent, cut short, or hinder the trip towards “the north” are also scenarios that serve to re-imagine this trip. This allows them to draw the road again and try crossing again. The border wall sometimes rises as an insurmountable obstacle. Other times it’s a hindrance negotiated without too much difficulty, with the right assistance and guidance.

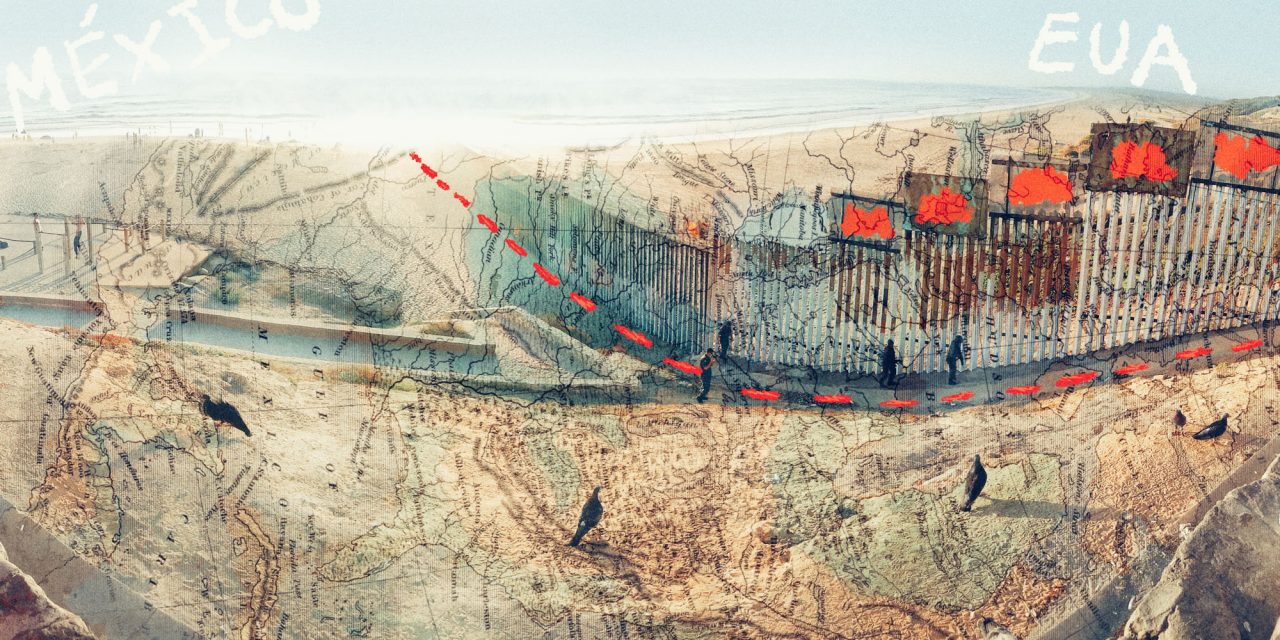

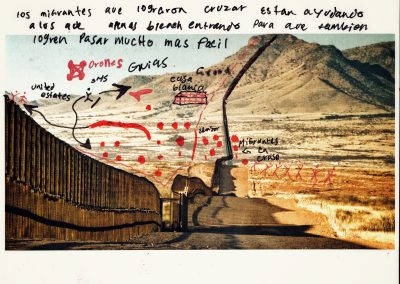

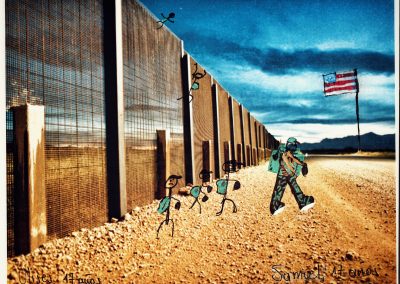

The images we present here are part of a series of interventions of photographs of the wall done by a group of Mexican adolescents deported by U.S. Border Patrol. They altered these images during their time at a government shelter in the Mexican Northeastern region. The images were created in a workshop, where the goal was to discuss the meanings and effects of the border on their life, and their decision to migrate. The group was formed exclusively by males, aged between 15 and 17, from southern Mexico and border states.

On the “empty” border landscapes, they stamped their experiences, claims, fears, and that which gives them the strength to keep going. While some images show the burden of frustration failing to cross, others reveal the persistence in their hope and will to reach “the other side.” Some lived traumatic experiences, because their life was in danger during the crossing, or they were recruited forcefully to smuggle drugs across the border. Whereas some advocate for freedom of transit and their right to find a better life, others drew and minutely described border monitoring technology, and the elaborate strategies used currently by “coyotes” to avoid the wall and travel through the desert without detection. Others reveal their anger towards the racism, xenophobia, and exclusion the wall represents as a challenge to their dream of crossing the border. Their unique and extraordinary experiences turn the border limit into a landscape populated by stories and memories, every day rewritten with the arrival of new adolescents and youths in search of a chance of crossing. In each case, the wall turns into the backdrop and symbol that enables visibility, expression, and materialization of dismay, indignation or rage caused by a border system that stands in their way, and the possibility of a “better” life.”

Javier’s Crossing

“God put me here, and it’s up to me take advantage of what comes next.”

Javier is a young indigenous man from the state of Guerrero. Almost two years ago, he had to leave his town after he was kidnapped and extorted by corrupt police authorities. Also, his nephew, a minor, was abducted, a neighbor was killed, and he witnessed an escalation of violence in his neighborhood. Javier made the decision to leave for the United States not only to flee from violence and threats but to gather financial means to get his family out of their current difficult situation as soon as possible.

His testimony permits us to understand the series of changes in the strategies for crossing and “coyotaje“ (migrant smuggling) through the border, over several generations. The generation of Javier’s grandparents emigrated from their town, located in the mountains of southern Mexico. A guide from the same indigenous community accompanied them. This guide trained himself during various crossings. Armed with the empirical knowledge and physical training of the peasant who knows how to find his way through the most challenging places. Years later, his parents’ generation emigrated thanks to an expanded network of coyotes or guides. This network worked mainly through community relationships, family ties, and a code of honor, that established the necessary trust for a journey. The knowledge and direct experience of this journey remained limited. These elements enabled placing trust in a single person who shared the native language and the same honor codes. At the same time, this person had the contacts needed on the other side of the border, that guaranteed migrants the ability to reach their place of destination in the United States.

Currently, Javier’s generation migrates in a very different way. The members of this generation have a better command of Spanish than previous generations. They’re fully aware of smart-phone technology. They are informed, give each other advice and support through social media. They also are in the know-how to be able to orient themselves using geo-referencing applications. All these elements enable them to cope in a world viewed as intimidating and unknown to their predecessors. Youths like him don’t need a guide to accompany them from the door of their remote communities. They apprise them of transport routes that reach the border and get there on their own, with instructions on how to move to the hotel where they must await further communication.

Yes, I found the crossing very difficult. But well, if God put me here, it’s up to me to take advantage of whatever comes..

Whereas before people depended on a single coyote that accompanied them throughout the journey, now young people like Javier make the crossing guided by a series of organized persons through a timely and efficient division of tasks. He won’t even have physical contact with many of them. He’ll only receive instructions via WhatsApp or a telephone call. Most dealings are anonymous, impersonal, brief, and completely oriented to the task or stage of the trip to be completed. Today, the work of guides from his town is not carried out based on the precepts and monitoring of the home community, but under surveillance and instructions of the “mafia” or the drug-trafficking cartels. The current border crossing strategies show a unique specialization and division of tasks. They reflect and are a consequence of the blossoming of an imposing economy based on human trafficking. They further show the impact of the growing militarization and hyper-monitoring of the border—also, the deep involvement of cartels that oversee, control, and manage each stage of the journey.

Besides enabling the understanding of this environment and its transformations, Javier’s testimony reports a very arduous personal experience of crossing the border, lived as a “rite of passage.” In other words, overcoming a challenging test would allow him to access a new stage in life and opportunities in the United States. This new life, although “illegal,” is also in an environment with no violence or threats to him and his family.

Currently, Javier lives in the southern United States and works seven days a week in an auto parts factory, on twelve to fifteen-hour shifts. He has no right to a single day of rest nor holidays. The pay he receives for each hour worked is lower than the salary paid to the American citizens that work there. It is also inferior to the compensation provided by law, but his migrant status precludes him from claiming any labor rights. He has to wake up at 4 am and drive for almost an hour to reach the factory before the workday begins. Imagining his future, he dreams of one day returning to his hometown in Mexico and building a small house, “even a simple house,” having his own business and supporting his family. He also knows, however, that if conditions in Mexico don’t improve and immigration policies harden, his return could be postponed for decades.

My guide, the person they call the “coyote,” he’s from my town. But now he works for them, the mafia. They don’t work as they did before. Previously the coyote brought you from your town. He took you across the border and then delivered you to your family. Whereas now, he doesn’t. Now I came alone from my village to the border.

Now everything is done by phone: the crossing, everything. To pay them, you don’t pay a person; you deposit an Oxxo. When you arrive at the border, they ask for a-thousand dollars to be in the hotel and [for them] to pick you up, and they take you across [sic]. But they take it from what they told you they would charge you [in total]. Once you cross, you’re in. Where they pick you up at the border, you pay another thousand. But a relative pays that. So, they can send you to Phoenix. From Phoenix, almost everything was paid already. They only leave the last part, about 700 dollars, until you reach your home. What you’re paying for is the raite [transport] to the place you’re going.

Before, the guides went all the way to your town to bring you, they transported you up to the border, and that same coyote took you across. He was your guide all the time. Perhaps arriving in Phoenix, he came with you and distributed all the people. But now you don’t know anyone of the ones that guide you. They only tell you by telephone. [The first coyote] speaks to the ones that will take you across. But those who take you through, it’s not only one. There are several of them. Because before, the [same] coyote took you across, but now they put you in alone, and they only guide you by phone.

There are two routes to cross through Naco and Bisbee, one goes up and the other down. The one up has to be quick because there are no trees. Everything is exposed. And if they see you, they catch you for sure. Whereas, on the other side, the different route, that is where to hide and everything. That’s how they guide us, only with the cellphone. That is, they show you a house where you’re going.

When you’re at the wall, they tell you: “The house where you’ll hide is there.” They show it to you with binoculars. But those who take you across is not only one. There are many! One goes with you and gets you up on the wall, and the others stay to check the cameras. Because there, where we crossed, is a mountain, already in U.S. land. And there [on the mountain] is a camera, and that’s the one that, well, it sees everything, down. On the wall, there are cameras and voice devices; and the guys that are up there are the ones who look out for the cameras. Because on this side there is another mountain with cameras that see everything, all the way down. [The coyotes] are on top of the hill looking over the camera. They see the camera below and check because the camera moves, it turns. And when the camera turns to the side where we are not, then they tell us to climb the wall. When you come down the wall on the other side, you run for it. You shouldn’t take too long, and you have to jump quickly. They carry the ladder and everything, and you go up.

The first time it was a little dangerous because I was about to fall. The tubes on the wall are very tall. I don’t know how many meters, but after the pipes, they put a piece of plate, and it’s high. My hand didn’t reach the top. And one couldn’t climb down because if you let go there’s no place to hold on. After all, the plate is smooth. I was going to fall. A lady fell and fractured something. She was like that when we arrived. She was there in the hotel. They say they couldn’t withstand her or let go of her because, on the other side, they tie you up to come down. To climb, they place a ladder, and to come down on the other side you slide down the tubes, they tie you up and untie you while you hold the pipe. Everything has to be quick when the camera turns and returns. They usually take us across at dawn, between four or five in the morning, because they know how everything is. They even know what time the one keeping watch on the line change shifts.

Then the guy that takes you up, he goes up there. They only are in charge of taking you up and guiding you until you reach the place where someone will pick you up. They show you the house, and they tell you on the cellphone, but they don’t run with you. They give us a phone, and they talk to you on the phone. Because once you get down the wall, you have to run about twenty meters or more. And after that, you start making your steps. First, you have to run very fast due to the camera [because] the wires with the sensor are there, if you touch them, it activates. The road where the immigration patrol passes by is there [to one side], on the very wayside. All the wires and also a wire mesh, and you have to jump over those, and they have sensors.

Once you pass that, you start running because they activate, and further ahead, there are more. This is why they [the coyotes] said: Don’t touch any wire. Try to cross it without touching it. That’s why we pass under it because it is this high, more or less [he indicates a height of about 20 cm from the ground], and that way, we passed under that. But it activated anyway because we also have a backpack. And more so since you’re in a hurry, desperate, let’s say, to pass!

The first time we tried, the patrol got there, because first, they got one [of us] in, but the immigration agents saw he got in and they followed him, but couldn’t catch up with him. We [the rest] waited about 30 minutes, and then they got us in, but we ran into them further ahead. Because the immigration agents didn’t leave, they were there searching, searching. When we got there, we bumped into them. We were a day or two in the icebox. They got us out in Nogales, and we came back to Naco. When that happens, the coyote doesn’t charge you again. I don’t know how many chances they give you. When you arrive, you pay a thousand, that’s enough. I don’t know, like five opportunities.

The second time I tried, they got me up [the wall] in another place. There the wall was higher, but there were tubes only. There were no plates. There again they throw the ladder. That was around nine in the morning. It was very cold. In fact, the camera saw where we were, because the patrol got there. We were there lying down for around an hour, two hours, hidden. We were still on the Mexican side, because the patrol was on the other side and wouldn’t leave. The camera saw us and alerted them, and the patrol got there. And we waited. I don’t know if the guys from immigration fall asleep or got distracted, but we went a little further, about a hundred meters more, and there they got me up [the wall].

Once I was on the wall, the patrol was nearby. I was told:

“You get down and make a run for it!

But in that place there are no trees where you can hide. I got in. And about twenty minutes [later] a helicopter started moving, because down, on the other side, where they take us across, they had caught someone. I was already [in] and they would tell me:

“Throw yourself down, because the helicopter is coming! And there were small trees, all dried up, and I hid there. I was alone, just with the cellphone.

Thank God, because the helicopter passed over me and couldn’t see me. And it’s also because they camouflage us, with military-like T-shirts. And they make us wear slippers, so we don’t leave a trail. That’s what set me back more, that the helicopter was there. It took me about eight hours to get there, because they picked me up around 5 in the afternoon, and I got in at nine in the morning. Very little by little I was moving ahead. There was a highway close by, and they told me [on the cellphone]:

“Pass under the bridge. There is no car right now, cross!”

So, from there I walked, but it was far. When I got there, I bumped into a coyote, but not the person, the animal. I got scared when I saw it. We just stared at each other and, in a while, it left. It looks like a German shepherd.

Then I kept going, and they were saying:

“Now, move on.” And I walked.

Then:

“No, stop. The helicopter is coming, throw yourself on the ground again.

There I waited about an hour, two hours. The helicopter wasn’t coming to where I was. But it was around there, near the border, on the wall, and so it wouldn’t see any movement, they told me:

“Wait.” And there I waited.

After that, I could keep walking. When I got to the town, to the outskirts of the town:

“Wait there. A van is coming like so, and so, and you’ll get in.

All that time just with the cellphone, nobody was guiding me. I was walking. The town could be seen at a distance, because it’s there, in the distance. It took me a long time, because I advanced a little. And I had to lay on the ground again and hide. There was a while when I did get desperate and I called my wife [in Mexico], and I told her:

“It’s been a long time and I’m here laying; they haven’t called back.”

I was starting to despair. I was feeling like going back. But she said to me:

“Don’t despair. Resist, they’ll call you now”.

At the same time, I was calling her, they’d already called her to tell her that I was in a safe place, so she wouldn’t despair that I was taking so long.

Finally, I could keep walking on, and I got to the place where they’d pick me up, and they told me:

“The car that’s coming for you is there. Have you seen it?”

“Yes, yes, I’ve seen it. It was coming from far off.

“When it passes by, you have to come out, because if the car passes you, it won’t come back for you.”

“Ok,” I said.

I got there to the side of a highway. I hid among the bushes, and the van came for me. It was an American lady. I got on, and she took me to the house where I was going to be. I was there, in that house, for about two days. It’s close to the border. I had to be there until they payed for me. From there they took me to Phoenix. You have to wait until they pay for you so you can go on. And you also wait for them to check the road, to see if there’s a roadblock or not.

I was picked up there and they took only me to Phoenix. I got where all the rest [migrant persons] were. We all got together there, in a house. The only problem was there was nowhere to sleep. We slept on the floor, and it was very cold. It was December. I was there about two or three days. There were some thirty or forty people. They prepared food for us and we all got served gradually. That house was in the middle of the city. It was like a neighborhood, same as here. It was like a normal town. There were houses. It had everything. People don’t suspect anything because we always arrive by night, they even get you out of the car outside, like normal. We got there at night, and they put us in the house.

There [in Phoenix] you have to make another payment again. It’s there where they get the whole thing. My brother sent a thousand dollars to the border. To cross the border, another thousand or two-thousand, and in Phoenix they got four- or five thousand more. From there, only seven-hundred dollars were left to get there. Because they were going to charge me one-thousand-five hundred, but they didn’t.

When I was in Phoenix, it was around December 20th, the person who was going to bring me said he didn’t want to work, because he was going to be with his family. That’s why he looked for a friend. When that person arrived, they got us in the car. Since there was no car coming here, I came with the people that were going to New York. They said we were going all the way to New York, and then they would drop me off [in Tennessee]. We were happy on our way, but on the one hand also scared, because we didn’t know what could happen. Then I fell asleep, and when I woke up, the driver was hallucinating, he was saying things.

Supposedly, he was going to feed us, but he didn’t feed us. We spent a whole night and day like that. He had been driving all night and day. And around seven or eight [the second day] he took us to eat. He spoke to his boss, and he recovered a bit. From there we got back in [the car], and we were relaxed. But then he started again. Around eight or nine at night, without sleeping, with cocaine only. He started saying things:

“You’re the ones calling [the police] now! Get out, and go tell the ones behind to leave me alone. I was just told: ‘Go and leave that people,’ But I don’t know what you’re doing here. What do you work in”?

He was Hispanic. He was saying to us in Spanish:

“I don’t know anything. They just told me ‘Go and leave the people.’ But I don’t work with them. If they catch me, I’m going to tell everything.”

We all got scared. I didn’t want to go with him anymore. A girl from Peru started to tell him to open the door for us to get out. The ten of us got out. But because they saw there was a patrol nearby, some got scared and got on the van with him again. Only a few of us left and went into a restaurant. That was on December 23rd. It was very cold. You went out on the street and your clothes felt like they were humid. Very cold! Then, the ones who were with me called a friend they have close and he came for us. Even when he wasn’t a coyote, but just a person, he charged us 200 dollars each for every night we stayed at his house.

My brother came for me at dawn. I don’t know anything else about the rest of them. I think they also went for them. Thank God we weren’t stopped on the way. I arrived at my brother’s house precisely on December 24 at midnight. His family was already preparing everything for Christmas. Yes, I found the crossing very difficult. But well, if God put me here it’s up to me to take advantage of whatever comes.

NUMBERS BEHIND THE WALL

Mexicans in the United States (2016)

%

Are undocumented

%

Have lived there for ten years or more

Changes in Migration Dynamics to the United States of Mexican Children and Adolescents

A 2016 estimate number of roughly 12 million Mexican immigrants lived in the United States. Forty-five percent of these lived there undocumented. According to estimates of the Pew Research Center, Mexico is the country with the largest number of immigrants in the United States. They make up 26.6% of all U.S. immigrants.

Since 2007, the number of undocumented Mexicans has declined by more than one million.

In 2016, 80% of unauthorized Mexican immigrants residing in the United States had lived there for 10 years or more, while only 8% had been in the country for five years or less, which shows a long-term intent to reside in the country.

Source: Ana González-Barrera and Jens Manuel Krogstad, “What we know about illegal immigration from México”, FactTank News in the Numbers, Pew Research Center, 2019, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/12/03/what-we-know-about-illegal-immigration-from-mexico/

Why Is this important

The migration of millions of children and adolescents from Mexico and all over the world is not a national security problem. It is the result of a widespread crisis of human rights violations. The rights of Mexican children and adolescents to migrate must be understood based on their needs, aspirations, and present and future desires. For this reason, Mexican government institutions that traditionally protect children must evolve to create new practices, actions of recognition, spaces for assistance, and care and protection mechanisms. Being a migrant child or adolescent is an increasingly common condition in our Mexico. The building of borders and walls that criminalize and punish children and adolescents, while denying them the right to move, are a threat to their life, integrity, and human dignity.

What Is the Situation?

In 2016, it was estimated that roughly 12 million Mexican immigrants lived in the United States. Forty-five percent live in the U.S. undocumented. According to estimates from the Pew Research Center, Mexico is the country with the most significant number of immigrants in the United States. They make up 26.6% of all US immigrants.

Since 2007, the number of undocumented Mexicans has declined by more than one million.

In 2016, 80% of unauthorized Mexican immigrants residing in the United States had lived there for ten years or more, while only 8% had been in the country for five years or less, which shows the majority’s long-term intent to reside in the country.

How to Get Involved

It is imperative to collect information and shed light on the causes that push children and adolescents from their homes and home communities, whether they choose to leave alone or with their families. Namely, historic inequality, lack of wealth redistribution policies, organized crime, territorial conflicts, land-grabbing, plundering of natural resources, and lack of development opportunities serve as root causes that transform the needs and ideas of the community, the indigenous people, and the peasants.

It is essential to support civil society organizations and grassroots groups that protect migrant children and adolescents by giving donations, offering voluntary work, and spreading the word of the important activities they conduct.

Footnotes

- Ana González Barrera, Jens Manuel Krogstad y Mark Hugo Lopez, “Many Mexican child migrants caught multiple times at border”, FactTank News in the Numbers, Pew Research Center, 2014, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/08/04/many-mexican-child-migrants-caught-multiple-times-at-border/

- Idem.

- Ana González-Barrera y Jens Manuel Krogstad, “What we know about illegal immigration from México”, FactTank News in the Numbers, Pew Research Center, 2019, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/12/03/what-we-know-about-illegal-immigration-from-mexico/

- Ruth Igielnik y Jens Manuel Krogstad, “Where Refugees To The U.S. Come From”, FactTank News in the Numbers, Pew Research Center, 2017, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/02/03/where-refugees-to-the-u-s-come-from/:

- Fuente: US Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions

![I say there should be no walls. We are all free. We [used to] go where we want, but now nothing is like that. You have to smile despite all this. I just want to fulfill the American dream. There is only one life, but a thousand attempts. Proud to be Oaxaca. I say there should be no walls. We are all free. We [used to] go where we want, but now nothing is like that. You have to smile despite all this. I just want to fulfill the American dream. There is only one life, but a thousand attempts. Proud to be Oaxaca.](https://infanciasenmovimiento.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/El-Muro-11-1024x770.jpg)

I say there should be no walls. We are all free. We [used to] go where we want, but now nothing is like that. You have to smile despite all this. I just want to fulfill the American dream. There is only one life, but a thousand attempts. Proud to be Oaxaca.

![I can only tell [my fellow countrymen] to be very careful when attempting to cross, by because they risk their lives a lot. They suffer cold, hunger, heat, thirst. !Freedom! No to racism. No more deaths. No more surveillance. Remove the wall I can only tell [my fellow countrymen] to be very careful when attempting to cross, by because they risk their lives a lot. They suffer cold, hunger, heat, thirst. !Freedom! No to racism. No more deaths. No more surveillance. Remove the wall](https://infanciasenmovimiento.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/El-Muro-10-1024x766.jpg)