EPIFANIO, MEMORIES OF A NA SAVI BOY

From the Mixteca and the Day Labor Fields

In 2005, I met Epifanio, a Na Savi (Mixteco) indigenous boy who had migrated with his family from the Montaña de Guerrero region to Oacalco, Morelos, in search of work in the fields as a day laborer. He was eight, and I was an Anthropology student. I was trying to do collaborative research with migrant children. From the very beginning, I was captivated by his intelligence, liveliness, and personality. Since that day, Epifanio “adopted me.” He welcomed me into his life, his family, and his world. He understood what I was searching for, and sparked my curiosity with the enthusiasm, generosity, and wisdom that only a child can bestow. He became the most important teacher, collaborator, and guide I could have ever come across. Since then, I have had the immense privilege of learning, working, and accompanying Epifanio in his journey through life.

Fifteen years after that first meeting, we have created together an audio-visual aid that shares decisive episodes in his life. With an extraordinary sensibility and intellectual clearness, Epifanio knows how to inhabit several worlds, and his history is a web where many roads and borders intertwine. These roads plow, divide, and also join discontinuous territories, cultures, languages, belongings, identities, families, and loved ones. His memory, his speech, his personality, and the way he looks at life are a result of an unceasing journey between his town, in the Mixteca region of Guerrero, and the fields for temporary laborers in Central and North Mexico, and various cities in the United States. He moved to the U.S. as a child in search of better financial and work possibilities.

The videos we show are the result of a dialogue that has extended for more than fourteen years, during Epifanio’s childhood, adolescence, and youth. It is a conversation with time for listening and a time for silence. These videos are the outcome of a journey in friendship, of being a godmother, of intercultural learning, solidarity and affection. They are also a long conversation intending to narrate through Epifanio’s experience and wisdom, the life of a Mixteco child and youth marked by constant migration. The videos emerge with the certainty that only someone like Epifanio could transmit. He exposes with such clarity what it means to be simultaneously a migrant, an indigenous person, and a child—deeply interrelated experiences. The videos communicate ways of being and of becoming someone that should be understood as inter-weaved.

This work is a tribute to a child who, from a very young age, witnessed his family’s separation by borders built up by inequality and financial vulnerability. A child who had to travel way too early through a desert that has killed an inordinate number of children and adults. A homage to a child who understood the meaning of being an indigenous person when he left his town for the first time and learned what it means to be a “foreigner” in his own country. A recognition to the child that took on the responsibility of minding for his mother and sisters to reach the “other side,” who buried a “small ‘time box’” with his most beloved treasures before leaving, hoping to recover one day the life he left behind. It is an appreciation of the kid who learned how to face racism, discrimination, and the worst contradictions of our economic and political system to become a young man of beauty, integrity, and freedom of spirit that knows no limits.

This exercise combines exercises in ethnography, autobiography, and memory to build the narrative of a journey that continues today for Epifanio, who, a short time ago, had to cross the border again in search of the means to earn the livelihood that his country has denied him. A journey that crosses many boundaries: territorial, ethnic, racial, cultural, linguistic, class, and even age. In recounting his life, Epifanio helps us understand that crossing and defying these limits is an experience lived through the body: exposed and in danger in the desert. An experience lived in one’s skin, whose color reveals him as an “outsider,” even in his own country. Something he experienced through his accent and manner of speaking, which stigmatized him as an “Oaxaco.” This experience representing and building off of the beliefs, knowledge, and abilities he inherited from his community, and that differentiated him from other children his age. In this exercise in autobiography and remembrance, Epifanio crosses one more border, the boundaries of time, to go back to his childhood and travel through the territory of recollection, to inform us what he felt and what it meant for that boy to become a migrant, to live crossing borders since then.

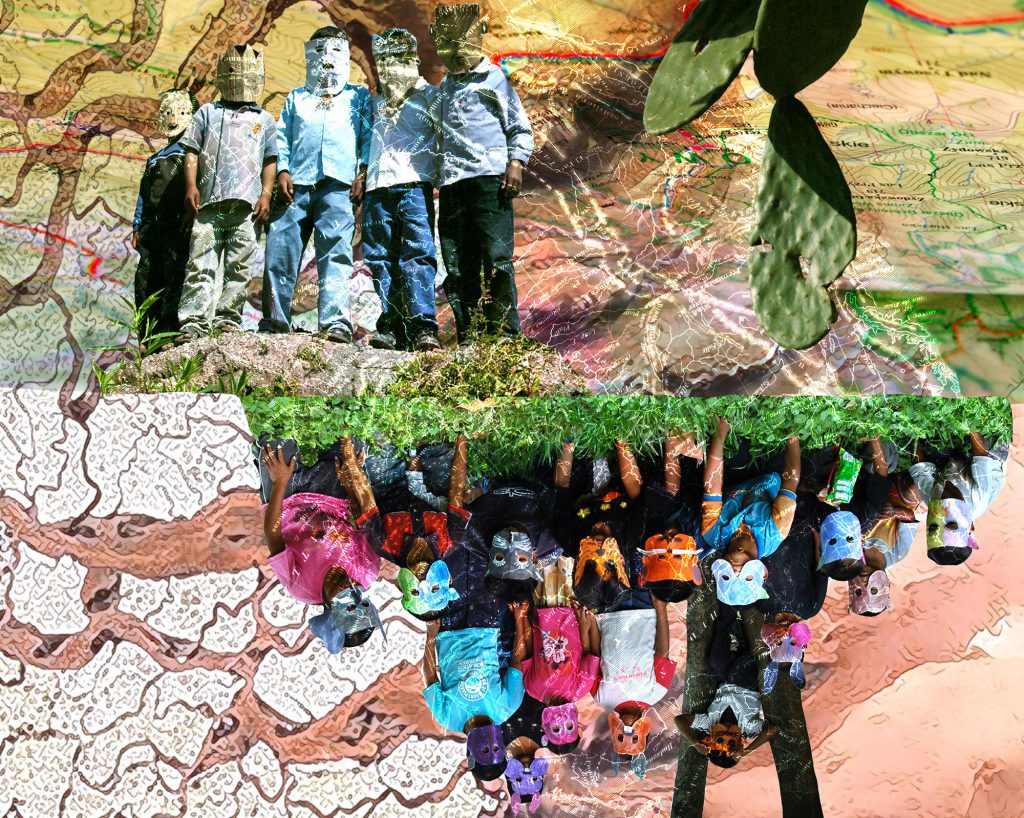

The creative process of these brief autobiographical short films has been especially important because, during the last years, they have sparked the creation of numerous workshops and spaces for collective reflection, art, and conversation with and among migrant children. The shorts have helped Na Savi communities from the Montaña de Guerrero—and their members who have migrated to Morelos, México, and to Alabama and California, in the United States—to meet and communicate again in social media, thanks to the photographs and drawings shown below. The films have also facilitated different kinds of conversations: intimate, familiar, collective, and communal, which had not taken place for a long time.

The visual material we present includes film, photographs, drawings, accounts, and animation in stop motion. It was produced by boys and girls from communities in Yuvinani, Guerrero, and Oacalco, Morelos, in Mexico, and Union Springs, Alabama, in the United States. To be able to relate Epifanio’s life through these materials is an exercise of commemoration and reaffirmation of the lives and wisdom of indigenous, peasant, and migrant children and youth in Mexico.

I. BIRTH AND LEAVING THE HOMETOWN

“My placenta is not here; therefore, I am there.”

The first video in the series narrates Epifanio’s first migration experience. He was born in a Na Savi indigenous community. A few years later, still a young child, he became a migrant in his own country. It is the story of the development of an ethnic identity and the birth of consciousness of a child who discovers the meaning of being an indigenous person in a mestizo society. These components intertwine with the experience of being a migrant at such a young age.

As signaled by indigenous tradition and knowledge, after birth, the placenta and the umbilical cord of the newborn must have a special treatment and bind to some element of nature: buried, thrown into the river, or hung on a tree. This fact determines the sense of belonging, personality, and destiny of the person who arrived in the world. Through this collective and familial act of welcome and opening of life, the Na Savi will forever be united to their people. Wherever they go, they always dream of returning.

I feel so proud of having been born like this, on a grass mat and a bed of fern. All culture comes tied [to you] from the moment you’re born. You’re born an indigenous person, Mixteco, you are marked and have a story from that moment on, from the day of your birth.

II – CHILD LABOR, FAMILY AND PEASANT LIFE CRISIS:

“My father saw that I had more strength.”

This video relates parallel experiences between the passion Epifanio feels for working the land since he was a child, the deprivation and hardship of livelihoods in agricultural labor, and the early separation from his family because of migration caused by poverty and precariousness. Epifanio’s childhood, like that of thousands of indigenous children and peasants, was marked by the experiences of learning the language, the worldview, and the customs of the Na Savi, growing and developing physically, socializing in the heart of an indigenous family and community. It is also marked by the intimate connection between all this and the knowledge of nature and peasant labor.

When they finally took me to work in the strawberry field, it wasn’t just going and being there. It’s something that you earn. My father knew and saw that I could do it, that I had more strength. He didn’t take us to exploit us but to teach us.

For me, starting work meant I could contribute more to our home. I could help my parents. Because I knew the field was beautiful, but I also knew it hurt a lot, since my parents always complained about their backs. They complained about their feet because they used to spend eight hours in the water, in the mud. I know the field is very painful because it’s a physical effort beyond the bearable. You bear it. You must bear it. You must bear it because otherwise, you won’t earn the day’s money.

III. CROSSING THE BORDER:

“This is the moment we’ve been preparing for.”

Epifanio describes the experience of crossing the border by the Altar Desert and the Mexico-U.S. border for the first time when he was eight. We can understand the amazement, fear, and responsibility he felt for taking care of his mother and sisters at such a tender age. His testimony helps us question the idea of the “American Dream” and grasp the differences of how adults and children experience migration, as well as their ties with places and people left behind.

I was very, very alert the whole way since we left home. When we got out of the car and touched the ground, I felt I was already in the desert. I said: “You were preparing for this a lot, now you have to be very alert, the danger is here.” We started walking, and I remember we passed a fence, and they told us: “From the fence to where we are, it’s the United States” Then I said: “Well, it was real easy passing into the United States,” but no, It was still a long way away. There were only women and a few men. The group was supposedly only for women because that road was longer but softer. We didn’t have to run like in other places where you had to make a bigger physical effort.

Silvia

Silvia’s story is the story of a Na Savi (Mixtec) girl that, after leaving her indigenous community has had to face and cross many barriers. Barriers of gender, class, language, identity, and race.

IV. RETURN TO THE AGRICULTURAL FIELDS:

“I found many children like me, who spoke an indigenous language.”

Many years passed between Epifanio’s return from the United States and the moment illustrated by this video. Here, already 23, he narrates his experience as a teacher of a group of migrant children day laborers in northern Mexico, very near the border where he crossed the first time. During the long period between his return to Mexico—when he was around 13—and the moment illustrated by the video, Epifanio finished high school. After that, he studied for a degree in agro-ecology at the Center for Rural Development Studies (CESDER), a college conceived for young peasants and indigenous people. This situation allowed Epifanio to continue working as a day laborer in different farmer’s fields in Central Mexico. Also, at this time, Epifanio had his first son.

When he was 23, Epifanio returned to the farmer’s fields of Sonora as a teacher of agro-ecology and the Na Savi peasant knowledge. He fulfilled his dream of working with indigenous children that shared his experience as a child migrant and child worker.

Unfortunately, this period was brief because these tasks rarely assure a financial livelihood. A few months after this, Epifanio had to emigrate once more to the United States, forced by financial need and lack of a salary to support his family. Currently, Epifanio works in an agricultural produce processing plant in California. His story, now as a young Na Savi, immigrant, and peasant is still writing itself.

BY THE NUMBERS: CHILD LABOR IN MEXICO

Million Child Laborers

Million Children Work in Non-Permissible Activities

%

Million Work in the Agricultural and Livestock Sector

WHAT IS THE CURRENT SITUATION?

According to information from the Child Labor Module, which is part of the National Survey on Occupation and Employment of the National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Computer Science (INEGI), in 2017, 3.2 million children and adolescents performed some type of child labor in Mexico. This figure is equivalent to 11% of the country’s population under 18. Of these 3.2 million, 2.1 million worked in a non-permissible activity. 34.5% of them worked in the agricultural sector, which accumulates the highest percentage of child labor in Mexico.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT SITUATION?

According to data from the Child Labor Module of Mexico’s National Survey of Occupation and Employment, in 2017 3.2 million children carried out some type of child labor, which is equivalent to 11% of the national children population. Of these, 2.1 million children worked in a forbidden occupation. 34.5% of them worked in the agricultural sector, which accumulates the highest percentage of child labor in Mexico, and is considered a hazardous occupation by the ILO.

How to Get Involved

It is crucial to demand that national and foreign farm businesses working in Mexico only produce products free of child labor. This demand should call for the removal of children and adolescents from production lines, and the guarantee of their right to education, food, housing, health, and healthy entertainment, as members of a day-labor household. At the same time, their parents may continue to produce the food we all consume.

It is fundamental to demand from local and national representatives from the leading agricultural states (Veracruz, Michoacán, Puebla, Jalisco, Estado de Mexico, Sinaloa, Guanajuato, and Sonora) that they enact better laws and public policies to protect farmworker families from labor exploitation. The DIF System, as well as state and municipal children and adolescent protection agencies, must do a better job protecting children and adolescents, so that families are not forced to find employment for their children in order to survive.