Some Leave, others stay

oThey leave with hope, they stay playing with memories

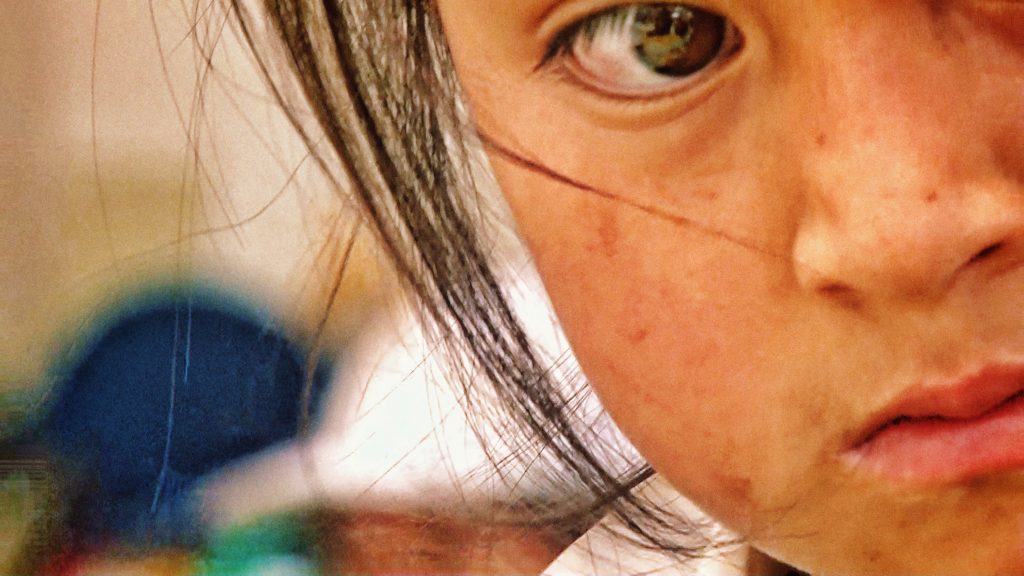

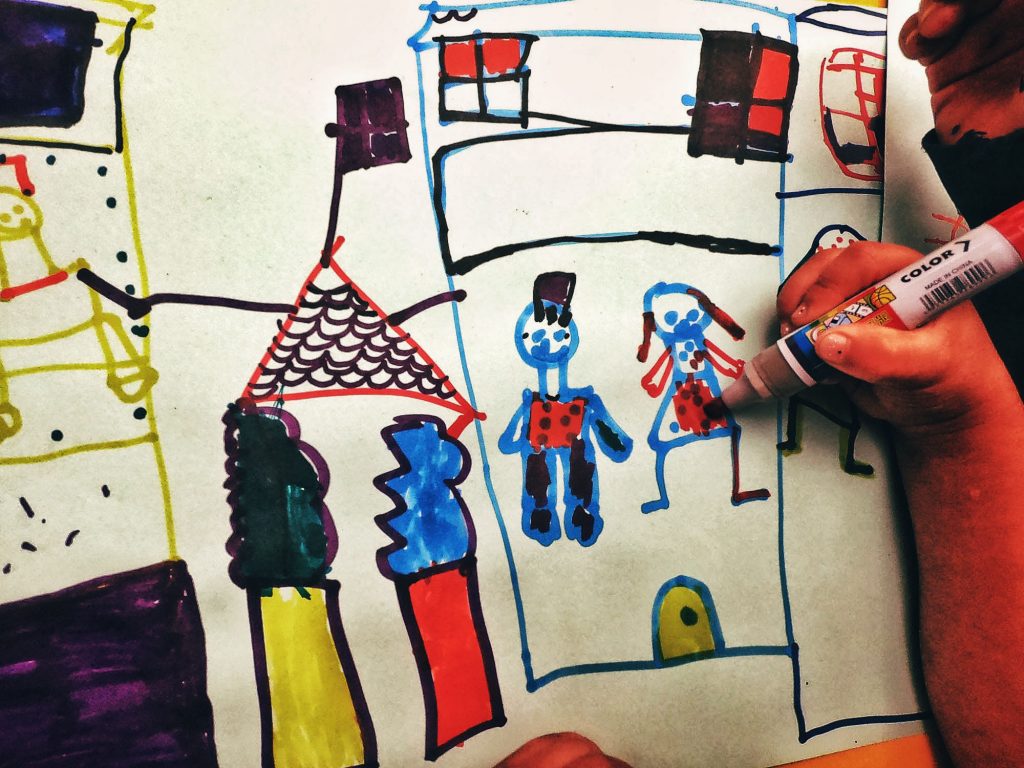

She is seven years old. The day we met, she wore her school uniform. We sat in the food court in the market. On the table, there was a box of markers and some pieces of white construction paper. She looked at me, grabbed the box, chose a piece of paper, and immersed herself into drawing. She was very focused, making strokes all the time. When she stopped, I took advantage of asking her what she was sketching. She looked at me again and explained: “This is my house. Here are my mommy and my grandmother, I’m here, and here, further away, my mommy is also there”. She finished this first explanation and lost herself again in her color strokes. At a given moment, I asked her about her mother, and I learned where she was. Without lifting her eyes or stopping her drawing, almost as if she was whispering, like, in fact, she didn’t want to answer. She told me: “In the United States.” Immediately, without me saying anything, she lifted her eyes and said: “But I don’t know how to draw the United States.” She lowered her eyes and continued drawing. She quickly moved her hands while she changed markers and added colors to her drawing. After several minutes she suddenly lifted her gaze and stated: “I’ve finished.” She had a dark blue marker in one hand and a black one in the other. They were the last colors she had used. While looking at her finished drawing, she told me what she had done: she drew the sun, a cloud, trees, and big windows in the house. Also, on the left-hand corner, over the second illustration of her mother, where she was out and far away from her house, she had designed a blue-black, very dark square. I asked her what that square was. Letting go of the markers, she stared at me and answered: “That’s the United States.”

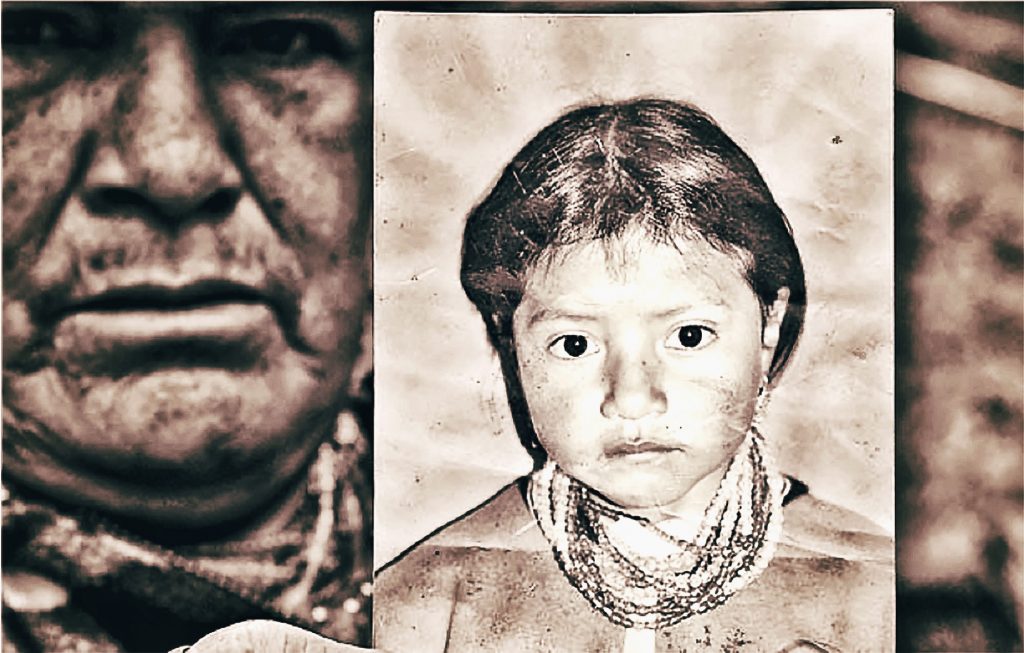

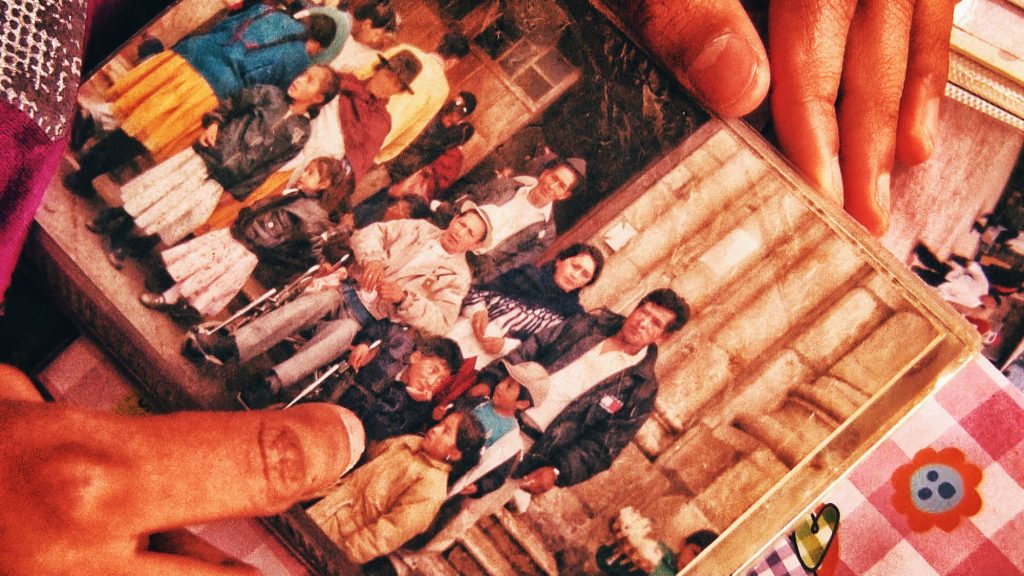

Dayana lives with her grandmother, her aunt, and her younger brother, who is four, in Gualaceo, Azuay Province. She never knew her father. She is the daughter of a single mother. When she turned four, her mother left “crossing the pampa” and, though she was twice detained and deported, she finally made it to New York on her third try, where she has lived the past three years. Dayana goes to school every day. She’s just learned to read and write. It is her grandmother who takes her and picks her up, and many times when school is over, she and her younger brother keep their grandmother company while she sells juice in the market. Including her aunt, the three support and take care of each other, and together they have invented a new way of living: in a house, like the one Dayana drew, where her mother, despite her absence, is still present in their daily life. That presence materializes in the voice Dayana listens to every day when her mother calls. Or it becomes an image through the photos her mother sends, or when they can see each other when they speak on the cellphone.

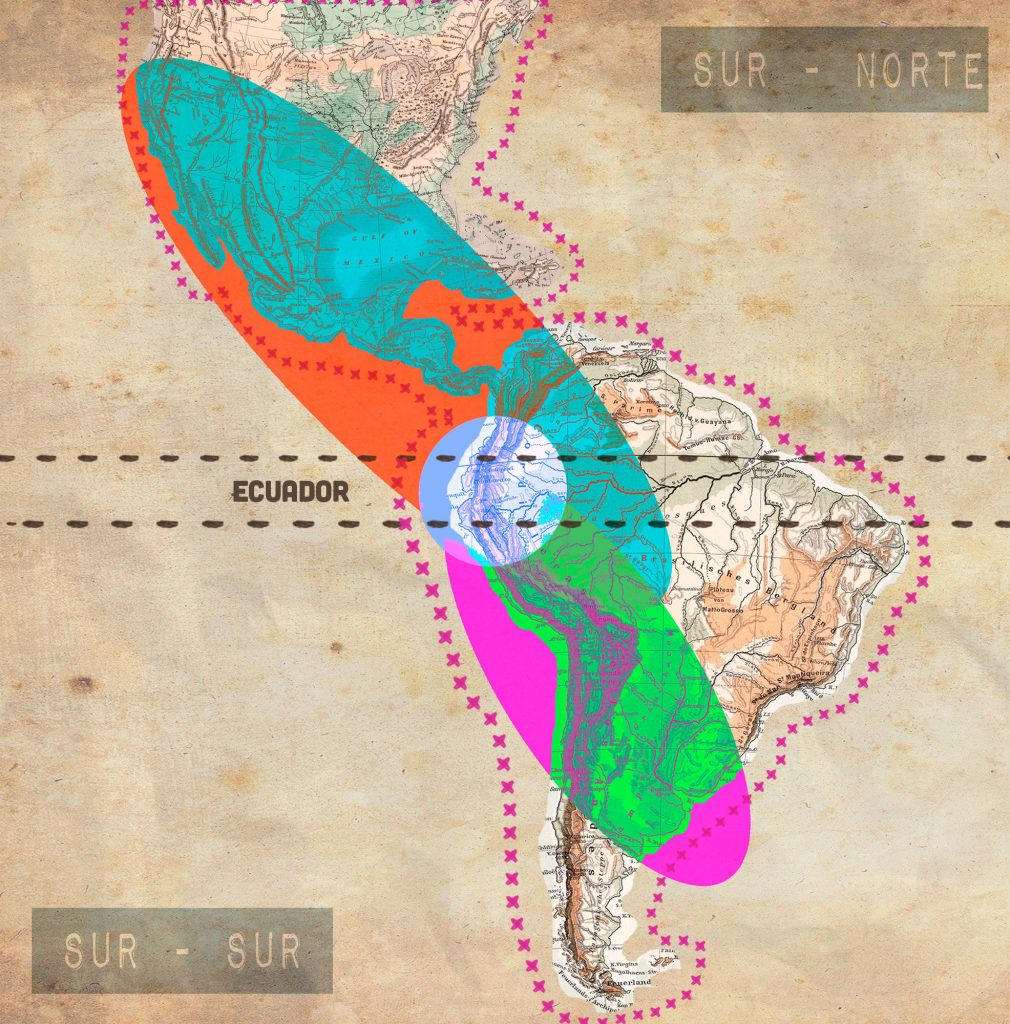

In a single drawing, Dayana clearly shows how migration has determined her life. Because she is the daughter of a migrant, she knows what growing up without the physical presence of her mother means, in her absence, minded by her grandmother. Hence, she paints her mother inside her house, next to her grandmother, showing the double-figure grandmother-mother, her daily support. At the same time, she draws her mother’s silhouette far from the house and under the blue and black square, the shape that until now represents that unknown place where her mother lives. And, of course, Dayana knows how to draw the United States, but she represents it like an abstract figure, like something unknown and distant. She hardly mentions that place. She only whispers it and darkens it when she paints it. Perhaps it’s because she associates it with missing her mother much. If she’s lucky, Dayana will reach New York still as a child. In a year, her migrant mother wants to send for her to be together. For this reason, she saves to pay the coyote who will bring her daughter and will guide her, as he guided her, in crossing the seven borders that separate Ecuador from the United States.

Like Dayana, more than 200 000 Ecuadorian children and adolescents have one of their parents or both of them living abroad. Because their fathers, mothers, or both parents have emigrated, mainly to the United States, due to the violence of poverty and historic socioeconomic inequality. According to the latest census in 2010, 37% of the people who emigrated left behind their sons and daughters in Ecuador under the care of immediate relatives. Most of these children and adolescents who stayed live and grow up with their grandmothers, aunts, or sisters, their new caregivers. This high number of sons and daughters of migrants also means that potentially they could well migrate irregularly later to reunite with their parents in the United States. This practice is, in fact, a constituent element of the historical memory of the primary migrant producing places in Ecuador, like the towns in the provinces of Azuay and Cañar, part of the so-called Ecuadorian Austral.

For all these reasons, emigration in Ecuador determines the lives of boys, and girls like Dayana, and of many adolescents. Since they are sons and daughters of migrants, they experience for themselves what it means to grow up in the physical absence of family members and, at the same time, the virtual presence of their family, minded by their caregivers, growing in reconfigured and transnational families. They are waiting for a day when their parents, their mothers, or both parents return or send for them, and they will also emigrate. The way they cope with the pain caused by the absence of their fathers and mothers, their numerous ways of imagining their presence, and of recreating their lives, conveys how these children and adolescents comprehend and undergo migration from Ecuador.

Who Stayed?

The Untold Stories of Migration in Ecuador

The numbers are of little help to perceive the complexity of the migratory experience. Percentages and numbers hide the faces, the voices, the gestures, the gazes, the stories, the memories, and the silences of those who feel and suffer the effects of migration. The thousands of examples are not necessarily what shed more light on this task of approaching migrant experiences of children and adolescents in Ecuador. Instead, the voices of a few, their individual stories, are what let us get near their lives and reveal those who have stayed.

Like Dayana, Mateo and Ángel, nine-year-old twins, live with their mother, Jima, while their father lives in New York. Evelyn, 11, lives in Cochapamba with her grandmother since she was born, because her mother left for Philadelphia. Janine, 14, and Rosemary, 16, sisters, heard news that their parents died in Chiapas, Mexico, in their attempt to reach New York. Their grandmother is raising both sisters and taking care of them. Jonathan, 16, was born in Nabón. His father and mother live in the United States. He lived with his father’s mother, then with his maternal grandmother, and now lives in Cuenca with his aunt and uncle, after being deported from Nicaragua while he was on route to reunite with his parents. And, Melanie, who just turned 18. She lives in Paute and never knew her migrant father. She only knows he lives somewhere in the United States.

They are children and adolescents of the Azuay Province. They have grown amid migration, not just because they are sons and daughters of migrants, but because their uncles, cousins, godfathers, neighbors have left “by the road.” And, because the fathers and mothers of their primary school and high school friends have gone this way. They all study. Every day they walk or take the bus to their primary or secondary schools. Some live in the countryside, others in cities. Some help with the harvest, others with sales in the market, and they are very technology savvy: they browse their caregivers’ cell phones and take good care of their phones to be able to communicate with their migrant parents. They ride bicycles, play soccer, and play with dolls; they like to eat candy, draw, read, collect stickers, and watch T.V. They are curious, they have many illusions. They smile, but they also feel rage, they feel some resentment because they miss their fathers and mothers. Because they still don’t properly understand why they are far from them. Hence, they fall ill and carry their grief in their gaze. The grief that at times seems to be dilute through their forgetfulness and the routine of their daily games.

At their age, they have a personal definition of who is a migrant. They know well what coyotes do, recognize migratory routes, and imagine the geography of the road from the stories they hear. They know about visas. They question the laws that stop migrants. With their grandmothers, they go on pilgrimages to leave offerings to the saints that protect travelers. They are children and adolescents that, when they are 7, 9, 14, 16, or 18 already know the grief caused by orphanhood, for growing up without parents, because they emigrated or have died on the road. At that age, they imagine their future lives: some of them want to be doctors, accountants, or psychologists. Others don’t want to study. Some of them are already aware of how and when they will migrate. Others say they will never go away for fear of leaving by the chacra for the United States, and more so of being separated from their grandmothers, the ones that have taken the most care of them. There are still others that, being children and adolescents, have emigrated, been deported, and want to try once more.

PLAYING WITH ABSENCE

Growing up With the Absence of Migrant Fathers and Mothers

One of the most challenging aspects faced by those who stay is coping with the grief caused by growing up in the absence of their fathers, mothers, or both parents. They miss them because of their physical absence. They left when they were newborn, a few months old, when they turned 4, 5 or 6, or became adolescents. The grief they bear expresses itself in their sad eyes, and in the tension invading their bodies when someone asks them about their fathers or mothers. In a migration context like the one these children and adolescents grow up in, that question becomes invasive, and it’s awkward. But they don’t sidestep it. Like Dayana trying to answer: her voice withdraws, her eyes lower, her body turns as if wishing to escape from her reality. It would seem that question pierces their soul because it reminds them that, even when they have their caregivers close, they carry the orphanhood left by the departure of their father, mother, or both parents. Facing this question, gradually, in their own way, some like a whisper, others like a cry of rage, they articulate and answer that their parents are not there. They live in the United States, that place alien to their everyday life. Immediately after coming to terms with their condition of sons and daughters of migrants, they give voice to their grief: “I feel bad, sometimes I cry because my mom is not here,” says Evelyn, 11, while letting nostalgia tinge her gaze. In contrast, Jonathan, 16, replies with a voice full of complaint and rage: “I feel lonely, I feel down, they’re not quite sure what’s wrong with me.”

However, not all who stay can articulate that clearly the grief they feel. Age is decisive: the younger the sons and daughters of migrants, the quicker they embrace the absence, play with it, or even put it away, even temporarily. Mateo, 9, for instance, understands this absence as follows:

I live with my mommy and my brothers. My daddy is working. He lives in the United States. He’s far away. My daddy says that it takes very long to get there. It’s been a while since he left, but one day I’ll get out of high school, and that day he’ll come.

Mateo, 9 years old.

Mateo knows that his father doesn’t live with him and is far away. He also has the certainty of his potential return: “When I get out of high school,” he claims, his father will come. That time of his own makes him somehow invent a way to grow in the absence of his migrant father. For Dayana, 7, the temporary understanding of her mother’s absence is very similar to Mateo’s. In her words: “One day, now, my mommy will arrive. She told me when I spoke to her yesterday, and she’s coming now.” For her, the “now” means a short time, even immediately, and though it’s not real, it is a temporary invention that becomes a consolation she understands and maybe calms the grief caused by missing her mother.

If the passing game consoles Mateo and Dayana and this allows them to make some sense of the situation, in the case of Melanie, an 18-year-old adolescent, in contrast, the fact of not recalling her migrant father alleviates her deprivation:

Since I never met him (his migrant father), it wasn’t that hard. When I was about 5, I spoke to him for the first time. But I don’t know, life would have it that I never talked to him again until a year ago […] When he contacted me through Facebook Messenger […] I don’t know where he lives exactly. In the United States, but I don’t know where.

Melanie, 18 years old.

Like Melanie, Janine, 14, has no memory of her father or mother. She is an orphan because her parents died en route to the United States when she was seven months old. As she says: “For me, it hasn’t been too difficult, because I never knew anything about them. For me, my granny is my mother.” The lack of that filial emotional experience, and the substitution of the grandmother-mother for the mother figure as the center of care, undoubtedly soothe hundreds of other children and adolescents, who like Melanie and Janine, were raised by their grandmothers and still are growing with them and are supervised by them.

Rosemary, 16, Janine’s sister, has another narrative to the same story.

For me, it has been tough, because I do have memories of them. I was three when I lost them […] It has been tough seeing other kids with their parents, and me with my granny. Even though I don’t have them, yes, yes, I can live without them.

Rosemary, 16 years old.

Rosemary clearly articulates it: to the extent to which those who stay keep memories of their migrant fathers and mothers, it is more difficult and painful to grow up with their absent presence. It’s like growing up in the middle of mourning orphanhood left by migration, because their parents are not physically there or because they died somewhere along the route to the United States. While they are kids, perhaps the sons and daughters of migrants come togethertemporarily as a form of resistance to the absence of their fathers and mothers; paradoxically, it is also something they start forgetting when they grow and that transforms itself in living memory of that absence.

This is how it’s been for Jonathan, who, from a very early age, was affected by orphanhood caused by migration, and, as he became an adolescent, he grew aware of this orphanhood. In his voice, his body, his gaze there is a complaint and much resentment because he still doesn’t understand why his father and mother emigrated:

They left to have a better life, but I don’t know what they’re thinking of doing. It’s tough growing without parents, because I must tell my aunt and uncle what I’m going through, but not my parents. […] The heart of a child will not always be the heart of a child; the heart also matures and grows. Eventually, you lose your mother. She should know if she loses a son or how she feels.

Jonathan, 16 years old.

The grief his “heart” bears, in words of Jonathan, eases off, if only momentarily, when absence becomes presence through calls or daily messages via WhatsApp, Facebook, or Skype, provided there is contact with the migrant parents and mothers. “My mother calls me every morning when she’s driving,” recounts Evelyn, 11. She waits eagerly and happily for that call, which usually occurs before she leaves for school. For Evelyn, hearing her mother is the confirmation that she thinks of her daughter, she cares and, being far away, in a way she is close and takes care of her. The same thing happens to Mateo, who’s 9. He doesn’t speak with his father so frequently, but at least once a week, and in his own words: “I talk to my daddy conversing. He calls I answer, and we talk.” In those conversations, he tells him something about school, of his life in the countryside with his mother and his brothers and listens to what his father tells him about his life in New York.

Even though the grief of the ones who stay is undeniable because they grow up in the absence of their parents, having their caregivers at their side, especially their grandmothers, calms the grief that comes from growing up and living in the absence of mothers and fathers. The caregivers are a lair of love, protection, and care. Thus, for many of these children and adolescents, their grandmothers are their other mothers. They are the ones who wake them up and put them to bed; who take them to school, who pick them up; who make their food; who pray with them and for them; who wash their clothes. Who comb their hair, who buy their toy cars, and who understand them more when they are kids than when they grow and become adolescents who question and demand. In their own voices:

My granny is like my mommy. I can’t imagine my life without her

says Evelyn, 11.

My granny is everything to us. She loves us very much, and we love her as well. I consider her my birth mother. I love her very much, and I’m thankful for all she’s done for us

recounts Janine, 14

If there is something that almost viscerally ties those who stay to their caregivers is the shared orphanhood left by migration. Given this situation, together, they reinvent their lives amid shared grief for their loved ones who have emigrated or died on the journey. The sons and daughters of migrants grow up in the absence of their fathers and mothers; their caregivers, in contrast, are “orphans” of sons and daughters. Sharing this void, bear similar griefs, sometimes makes these children and adolescents also take care of their caregivers. They hug them, and they look at them, speak to each other, feel each other, understand each other. And when they can, they help them with the household chores and even in their daily jobs, housekeeping, taking care of the chacra or selling in the market. They pray for them and with them, and never imagine a life away from them. In extreme cases, like Janine and Rosemary, who are full orphans, the awareness of the care given by their caregivers is even more profound. In their own voices:

We take care of her and know she was very affected because she’s a mother who lost a daughter. I understand my granny’s pain. She had to be strong for the two of us,

says Rosemary, 16.

My parents’ dream was to go there (the United States) to pay their debts. My granny inherited all their debts. She had to work to repay them, and that was too tough. She also had two girls to take care of and had to work very hard,

Janine, 14, tells me.

The absent presence of their fathers and mothers is, without doubt, decisive in the lives of these children and adolescents who have stayed in Ecuador. It demands of them to understand and give their personal answers to the orphanhoods that migration has left in their lives. It’s not always easy to bear that grief. In fact, like Melanie says: “Though most of us in high school had parents in the United States, we didn’t talk about that.” It seems the sons and daughters of migrants retain the memory of the grief left by absence, and it’s something they do not always share. Jonathan has also experienced this: “I very seldom talk to my classmates. I don’t like it because it reminds me of my situation.”

Dayana, Mateo, Ángel, Evelyn, Janine, Rosemary, Jonathan, and Melanie are sons and daughters of migrants. They go to school and live in one of the historic migrant-producing provinces in Ecuador and have not received any guidance or support for their situation from the educational institutions they attend. They all agreed that they don’t study any subject, nor have any reading or discussion space on the implications of migration.

Rosemary, 16, claims that being the son or daughter of a migrant, “is a delicate and tough issue, but it would be good to unburden oneself.” She and her sister coincide that for cases like theirs, in whichthey lost their father and mother, more support is needed from primaries and high schools. And given the real violence on the route Ecuador-Central America-Mexico-the United States, the disappearance and death of migrant Ecuadorians multiply, and many of them have likely left sons and daughters in Ecuador. For this reason, those sons and daughters of migrants also mentioned it would be crucial to have spaces in school to speak with other sons and daughters of migrants about the mutual grief they bear at their young age.

Listen: voices of those who stayed

LIKE CHUTES AND LADDERS

The Border, the Road, and Migration

The daughters and sons of migrants not only keep in their memory and their skin a vast knowledge about the orphanhoods left behind by migration. The children and adolescents also have their notions about various aspects of this social process, which has determined their life and that of their communities.

What does a border mean for you? This question is not alien to the sons and daughters of migrants. For the youngest, however, it’s still a very complex abstraction, and they can’t answer. Among the older ones, the question is neither hard nor awkward. Indeed, they don’t hesitate to explain. They all agree that the border is a limit between countries, and they go further, because when they imagine the border, all of them think of the biggest one, the same one: in essence, the border separating Mexico from the United States, and they develop their answer based on this understanding. Here are some examples in their own voices:

A border is what divides the United States and Mexico,

says Evelyn, 11.

The most challenging place a migrant must cross because their lives depend on it

Janine, 14.

It’s the most difficult road to arrive in a big city where one can work a lot, and they can earn money,

states Rosemary, 16.

In Cochapamba, they imagine the border between Mexico and the United States. From Girón, they know what happens there. And this is no coincidence. On the one hand, their knowledge of migration derives from their own life experiences, from what they listen to in stories, mainly told by their caregivers, about how their fathers or mothers migrated, or from what they learn from their friends at school or their neighbors. It’s also a knowledge emerging from what their folks tell them when they call. On the other hand, their answers also confirm how the externalization of the border with the United States in the southern part of the continent affects the lives and memories of all migrant subjects, including Ecuadorian children and adolescents. In this case, mainly because to arrive at the final US destination, their parents and mothers had to face violence at the border check.

Perhaps characterizing a border is not as complicated as answering the following question: What do you think a migrant is? This question resounds in their own lives because their fathers, mothers, uncles, and aunts, neighbors, brothers, and sisters, or even themselves, at their young age, have been migrants. To answer it, they stay quiet and wait; they take their time. Dayana, 7, answers directly: “My mommy who left.” For her, a migrant is someone who has left. For Evelyn, 11, it is “someone who leaves to work or to see his or her family.” Rosemary, 16, states that it is somebody who “seeks a better life.” And Melanie, 18, replies: “A migrant is someone who looks for something more in life.”

If you add the following question to the previous one: Why do migrants leave? The answers reflect more clearly a more elaborate understanding of their own story. This understanding only occurs as they grow up. They also comprehend more fully why there is a complaint about the absence of their fathers and mothers: “To seek a better life maybe in other places, perhaps where you earn more money,” says Janine, 14. For Melanie, however, to migrate “is leaving everything behind for a dream. But what’s the use if you’re not with your family”. And that same complaint is present in Jonathan’s answer: “They leave, but without their children […] They leave alone, only thinking of themselves, and in the end, they are the ones that lose.” Thus, between defining what a migrant is and understanding why they leave, there is a usual answer: “They don’t forget their families,” Evelyn insists as a retort. The rest of the daughters and sons of migrants share this idea. It seems like more of a plea to their migrant parents.

The knowledge of migration the ones who stay have accumulated includes what’s implied by “ the road.” Insofar as they collect more stories of how their relatives departed, or of personal experiences, they learn the migrant geography that is part of the route that connects Ecuador with the United States, via Mexico, by air, land, or sea. They know how to leave through Colombia, Peru, or Bolivia, and then you must keep on until Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico, to then cross the main border and arrive in the United States.

Not only do they know geography, but they also know of the violence along the route. They know that people disappear or die because that happens to their own people. With eyes full of bravery, for instance, Janine, 14, recounts her experience: “My parents died on the Chiapas bridge. They had an accident, and they died.” In Jonathan’s case, however, the knowledge of what happens on the road emerges because he was detained and deported. “Better not to speak of these things,” he says, and goes on: “We got to Nicaragua, but we couldn’t pass. It was tough and frustrating”. This adolescent, 16, finds it very hard to talk about this experience because he was convinced he was going to make it. He thought it would very easy to leave by the road to be with his parents. That was and still is his biggest wish.

At 8, Jonathan was sent to look for his parents. His relatives handed him over to a coyote. From Ecuador he traveled by land to Peru, then continued by plane to Nicaragua. When he got off the plane, immigration police detained them and made a lot of questions that neither he nor the coyote could answer. For this reason, both were deported.

In Ecuador, to leave by the chacra, the pampa, or the road, it’s not only a practice among migrating adults. Since the nineties, because of the impossibility of generating a reunification process without taking into account the immigration status of the parents in the United States, like Jonathan, hundreds of Ecuadorian children and adolescents have emigrated with coyotes. In contrast to Jonathan’s experience, every day, many arrive and reunite with their migrant fathers and mothers. Currently, coyotes offer different routes to cover the 5 000 km between Ecuador and the United States. The itineraries combine air and land transportation to cross the extent of the corridor from the Andean Region-Central America-Mexico to the United States. From the United States, the fathers and mothers pay coyotes between US$ 10 000 and US$ 20 000 dollars to send for their children. The coyotes offer three attempts at crossing to arrive at the final destination. The same way that Central American children and adolescents face forms of violence on their journey to the northern country, Ecuadorian children and adolescents face different types of violence along that long road. Among these theft, extortion, discrimination, individual or collective kidnapping, trafficking in persons, torture, rape, accidents, disappearance, and even death. Local authorities, immigration agents, thieves, local cartel members, residents of border regions, or coyotes can carry out these types of violence.

Leaving Ecuador is never easy because the sons and daughters of migrants must leave behind their caregivers, and because at a young age, they must face different types of violence. As an example, in 2014, the Ecuadorean girl Nohemí Álvarez, 12, died in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, on her second attempt to get to the United States to reunite with her parents.

Life experience and, above all, the accumulated knowledge that the sons and daughters of migrants have is the basis to build their geographic image of the United States that faraway place where their migrant parents are. Some say that the country “is wonderful,” like Evelyn, or that “it’s beautiful and has lovely stores, and everything, and everything,” like Mateo. At the same time, they are aware of the dangers along the route and thus say “they are afraid of going” to that place, like Evelyn claims, or in contrast a place “I don’t like talking about, because I don’t know it,” as Angel argues. Age and comprehension maturity about the United States undoubtedly weigh in this construct. For Janine, “It’s where many persons look for a better life, risking their lives, yes, to get ahead and realize the American dream.” While Jonathan, in contrast, argues that “life in the United States is also hard because of what Donald Trump is doing, getting people out.

The accumulated knowledge of those who stay also allows them to reflect if they will emigrate in the future as their fathers and mothers did. Melanie, for instance, states: “People keep leaving, last month five persons left this very place […] I wouldn’t like to emigrate leaving by the road. I mean, with papers, yes, but not with a coyote, it’s a great deal of suffering.” She knows of persons who haven’t arrived and of dead people on the road. Thus, she insists that she would not emigrate with a coyote. Evelyn, in contrast, doubts, not for fear of the way, but because she wouldn’t like to leave her grandmother: “Sometimes I don’t, and sometimes I do. But I will miss my granny.” Jonathan and Janine are standing by their decision to leave, regardless of the implications. The former says: “Yes, I would like to leave to be with my father there, to meet him,” the latter replies: “I would leave after 20 because I would be more a woman, I would be more mature and I could make a good decision. No matter how I leave from here. If I’d get the visa, I’d leave by plane. If not, I would walk.”

In their wish to emigrate, the much desired and belated meeting with their fathers and mothers is present. Also, there is imagery, transmitted from one generation to the next, of what the United States is. An unknown place or a “beautiful” place, according to the construct, where they could realize the numerous life projects they’ve been developing since they were children.

Those who stay imagine their departure. From those towns in the Ecuadorian Austro, they traverse in their imaginations the long way that separates Ecuador from the United States. Since they are only children and adolescents, they accumulate knowledge about migration and becoming aware of the damage and implication of coming and going, of detention, deportation, of their itinerant lives. Far, very far from being passive subjects, fragile or mere victims of migration, from a very young age and subtly they quietly learn to take care of themselves, to think of their present and their future as sons and daughters of migrants, and to look after their grief. They have learned to grow amidst family reconfigurations and adding new meaning to who takes care of them. They turn into grandchildren-sons and daughters of their childless grandparents. They become children of their grandmothers-mothers. They understand in many ways the spatial and temporary distance that escapes traditional cartographic representation that delimits a space and sets a range. They also have reinvented their homes, their schools, their spaces, and, though bearing the grief caused by absence, they don’t necessarily live daily dramas or tragedies because they are sons or daughters of migrants. They are aware of their situation, but, like Dayana, they grow up in houses built amongst numerous geographies, at a distance, and with many forms of care. They are children and adolescents that live in various types of families, they suffer in their bodies the grief of absence, of departure, and everyday choose to fight to stand up, to resist and go on facing the orphanhoods left behind by emigration.

A Day in Dayana's Life

Dayana’s day starts at 5:00 in the morning. Her grandmother wakes her up at that hour. She must get ready for school, put on her uniform, have breakfast, check her school supplies. With her grandmother, she takes the bus from the rural community that they live in, Cochapamba , to the city of Gualaceo, where the school is located. This seven-year-old girl likes to have the hot oatmeal colada her grandmother prepares and a bun for breakfast. When she’s ready to leave, it takes an hour to cover the distance between her house and the school. The bus goes slowly. Operating the route Cochapamba-Gualaceo isn’t that easy: the downward winding road confirms the rough geography of the Ecuadorian Austro amid the Andes. If they don’t run into any problems on the way, Dayana usually arrives at school ten minutes before seven on the dot. Her grandmother blesses her every day before saying goodbye and reminds her that in six hours, at school dismissal time, she will be at that same place to pick her up.

The daily school bell alerts Dayana and her second-grade classmates that classes are about to begin. She likes going to school very much, playing with her friends and learning. “I like math, but I like more drawing and going out during recess,” says this daughter of migrants. Among her classmates, there are also other sons and daughters of migrants. It’s something that Dayana doesn’t know, or if she does know, she doesn’t mention it. Her grandmother, however, is the one who’s worried about it. Because taking care of her beloved granddaughter involves knowing the boys and girls who Dayana shares her games and daily learning with.

The school day ends at one o’clock sharp. At that hour, Dayana’s grandmother picks her up at the school entrance, precisely at the same place where she leaves her every morning. From school, they generally walk to the Gualaceo market, where she has a natural juice stall where she works every day. They don’t go back home immediately after school, instead, they return at sunset when the grandmother ends her working day. Dayana eats lunch at the market and keeps her grandmother company while she sells juice. If she has any homework, “I use the opportunity for her to do it.” If she doesn’t, Dayana plays with other boys and girls: “I don’t like to have homework, because I want to play and be with my granny,” says Dayana. According to her grandmother, though she doesn’t like schoolwork, when she has any, she really does it well, and this is reflected in her good grades at school. It’s during their time at the market when Dayana’s mother usually calls her from New York. She doesn’t call every day, but she does call very frequently. Dayana tells her a few things about her daily life, about school. Her grandmother says that her granddaughter likes talking to her mother but doesn’t tell her that much. When she gets the call, she listens to her mother’s voice, answers her, and recounts a few things about her daily life. “She misses her,” the grandmother adds, “and that’s why I think she doesn’t talk.”

Around six in the afternoon, Dayana and her grandmother begin their return home. Again, on the bus by the winding road. In an hour, if there is no traffic, they will get to their small house located on a hill in the town of Cochapamba. After dining on whatever the grandmother has prepared, they pray together, and then Dayana goes to bed. The next day she will start her daily routine all over again, always holding the hand of her grandmother, her beloved caregiver.

A Day in Jonathan's Life

At 16, Jonathan is in his fourth year of secondary school. His school is in the northern area of Cuenca, the capital of the Azuay Province, and one of the biggest and most important cities in Ecuador. He’s an urban adolescent. He lives his day walking the streets of Cuenca to go to school and then heads back to his uncle and aunt’s house; he has lived with them for more than eight years. He also strolls down the streets to see what’s going on. At precisely eight in the morning, his school day begins. To arrive punctually at school, Jonathan wakes up at six in the morning, gets ready, and leaves the house with just enough time to walk and take two buses. He doesn’t like any of the subjects he studies. What he wants the most, he says, is to graduate and finish school. Drawing is what he likes best. He’s drawing all the time: during classes when he tires of paying attention to his teachers; during recess, when he doesn’t want to spend time with his classmates; at his aunt and uncle’s house when he doesn’t feel like telling his relatives how his day has been. Drawing is his refuge and his escape for the grief he feels for growing up far away from his father and mother, both immigrants in the United States. He draws landscapes, comic strips, cartoons that, in some way, reflect his mood. As he states: “I feel lonely, I feel low, and they’re not quite sure what’s wrong with me.”

The grief he bears as an effect of immigration is clear at times, especially when he is with his school friends. Even though he doesn’t enjoy the subjects much, least of all the exams or homework, he does enjoy friendship and learns from it. Whit his “friends from school,” as he calls them, he doesn’t talk about his parents having emigrated, or that he lives with his aunt and uncle, nor of his deportation in his attempt to reach the United States; less still about the growing pains of living with his parents’ absence. He doesn’t like to talk about that. However, he talks about music, about movies, he laughs, he plays, goes out to have fun. He fills his life with vitality. Thus, when the school day is over, he usually walks along the streets of Cuenca with one of his friends and, when he strolls through the city, he dissipates his grief. Jonathan enjoys roaming the streets, looking at shop windows, going to parks, simply roaming. He’s usually back at his aunt and uncle’s home at sunset, shortly before dinner. In this family space, where the family gathers, when the mood is right, he talks to his and his aunt and uncle and cousins about the day. He speaks little, according to him. As soon as he finishes dinner, he locks himself in his room. He likes being alone. This loneliness and his silence always inspire him to draw. At that time, Jonathan says he thinks much about his life, about his father and mother’s departure. He imagines his future and looks at himself leaving. Jonathan would also like to migrate, go to the United States to study, but also to experience how his parents live there, in that destination known so well to him, though he has never lived there. During the night, he finishes his unfinished schoolwork. He likes going to bed late and takes advantage of the silence in the night to draw before starting his daily urban routine again.

BY THE NUMBERS: THOSE WHO STAY

ECUADORIANS LIVE ABROAD

%

LEFT THEIR CHILDREN IN THE CARE OF SOMEONE ELSE

CHILDREN LIVING WITHOUT THEIR FATHERS AND MOTHERS

Why is this important?

By the chacra, by the pampa, by the road, with counterfeit documents, with a visa, without a visa, they have traveled to that destination in such quantities that today 738 000 Ecuadorians live in that country and make up the tenth largest group of Latin American migrants in the United Statess.

Thirty-seven percent of the Ecuadorian emigrant population left behind sons and daughters in Ecuador under the care of immediate relatives. Data from the Observatory for the Rights of Children and Adolescents confirm that 2% of children, accounting for more than 200 000 children and adolescents, have at least one parent living abroad. Most of these children and adolescents who stayed, live, and grow up with their grandmothers, aunts, or sisters as their new caregivers.

In Ecuador, this has produced a chain of orphanhood: mothers that lose their children; children their fathers, their mothers or both parents; grandmothers that lose their grandchildren; and whole communities that become deserted.

What is the current situation?

Emigration in Ecuador determines the lives of a whole generation of boys and girls, and of many adolescents. Since they are sons and daughters of migrants, they experience growing up in the physical absence and, at the same time, the virtual presence of their parents, minded by their caregivers, growing in reconfigured and transnational families, awaiting the return of their parents.

How to Get Involved

We must understand that migration is a phenomenon that involves us all. Global structural inequalities are forcing millions of people to abandon their homes in search of a life of dignity for their families.

Documenting and sharing the stories of those who stay behind and of their caregivers is necessary to avoid them being invisibilized. In this way, can we spark a dialogue on what our responsibility is as a society, and how can we forge bonds of solidarity in Ecuador and across the whole continent to ensure these children have a decent future.

Footnote

- Observatorio de la Niñez y Adolescencia de Ecuador (ODNA), Los niños y niñas del Ecuador a inicios del siglo XXI. Una aproximación a partir de la primera encuesta nacional de la niñez y adolescencia de la sociedad civil, Quito, Observatorio de los Derechos de la Niñez y Adolescencia, 2010.

- Idem.

- “Externalizar la frontera” es un término para referir el mecanismo de control migratorio ejercido por Estados Unidos, por el cual se adoptan y adaptan mecanismos similares de control migratorio en terceros países, por ejemplo, en México.

- Álvarez Velasco, S. y M.C. Ruiz, Entre el enfoque de derechos humanos y las lógicas de seguridad y control: Análisis de las políticas públicas en torno a la trata de personas y el tráfico de migrantes en Ecuador (2004-2016), Quito, Save the Children, Flacso, 2016.

- Álvarez Velasco, S. y Guillot Cuéllar, S., Entre la violencia y la invisibilidad, un análisis de la situación de los niños, niñas y adolescentes ecuatorianos no acompañados en el proceso de migración hacia Estados Unidos, Quito: SENAMI, 2012.

- Álvarez Velasco, S., Frontera sur chiapaneca: el muro humano de la violencia, México, CIESAS-UIA, 2016.

- “Nohemí muere al segundo intento de ir a EE.UU.”, El Telégrafo, 22 de marzo de 2014, https://www.eltelegrafo.com.ec/noticias/informacion/1/nohemi-muere-al-segundo-intento-de-ir-a-ee-uu

Methodology

This text arises from a multi-sited ethnography developed in the Azuay Province, Ecuador, between January and September 2019. The places where the ethnographic immersion took place were the following: Cuenca, Gualaceo, Cochapamba, Jima, La Moya, Girón, and Guachapala. Most testimonies were collected during September 2019. In-depth interviews were conducted with twelve caregivers and fourteen sons and daughters of migrants, reconstructing their biographical path and emphasizing the migrant experience in their lives. These thoughts draw upon two previous pieces of research. Firstly, the exploratory ethnography began in 2016 during the first immersion in the field for my doctoral research, where I analyzed the historical and contemporary production of Ecuador as a global space of migratory transit. See S. Álvarez Velasco, op. cit. Secondly, this piece builds on the research included in the book by S. Álvarez Velasco and S. Guillot Cuéllar.