Silvia: From being a farm worker to a young refugee

“one learns to travel the world this way”

“Hello, my name is Silvia Pantaleón Martínez. I come from Guerrero.”

“What would you like people to learn about you, Silvia?”

“Well… How we lived before because we had such a big need. We didn’t have money. We didn’t have anyone to help us. That’s what I want people to know about me. That there were more people interested in seeing our world like it really is. Many people pass by and see how we are, but they don’t know how we suffer, what we experience daily. That’s why now, with photos, images, cameras, we show the world the reality of how we live.”

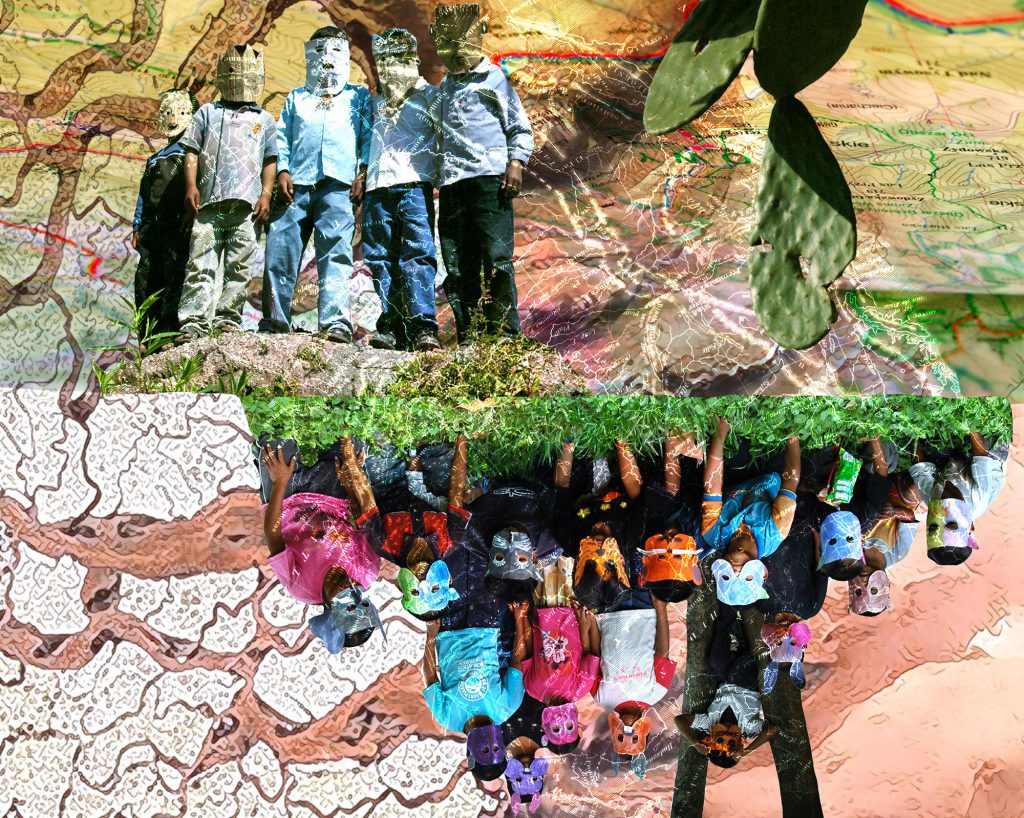

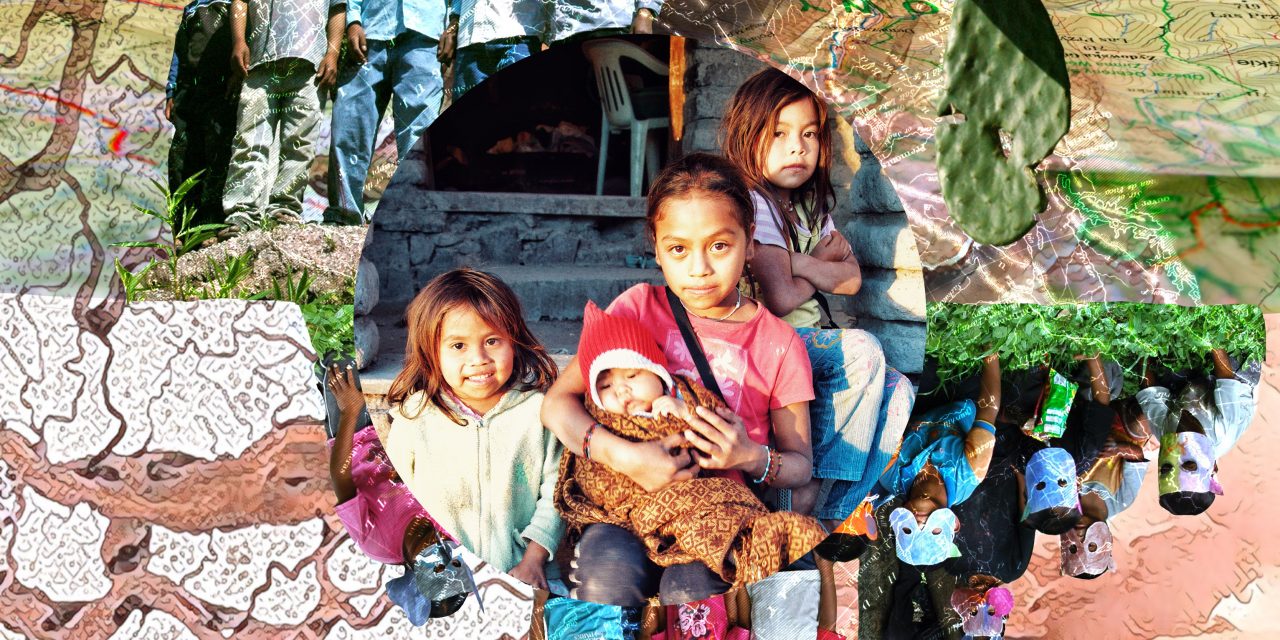

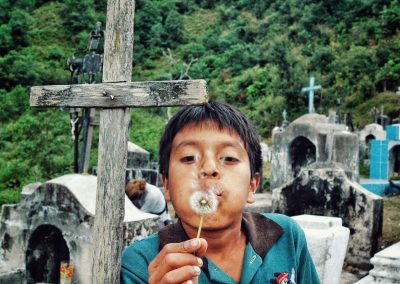

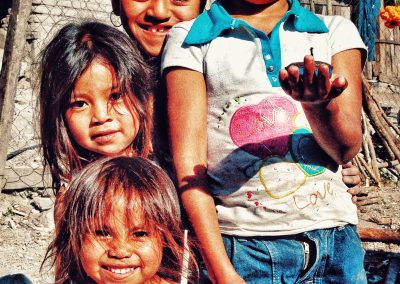

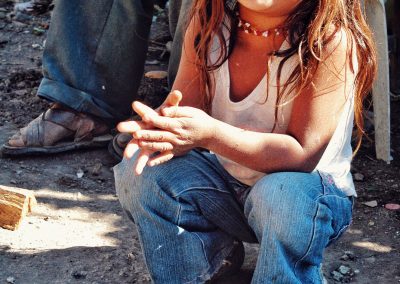

Silvia’s story is the story of a Na Savi (Mixtec) girl that, after leaving her indigenous community has had to face and cross many barriers. Barriers of gender, class, language, identity, and race. Here we present, in short-film form, a narrative we have been building as a dialogue at different times and with different rhythms since Silvia was eight years old. The conversation started in 2008 with workshops in art, theater, and games. In these workshops, Silvia, her sisters, and other girls and boys from her migrant community narrated their lives—expressing the yearning that migrant children feel for their hometown—, and shared their ethnic knowledge. This narration continued in a photography workshop and a series of interviews in which Silvia and her younger sister, Carolina, shared their experiences in Mexico as indigenous and migrant day laborer children. These experiences are the basis of the two stop-motion animations that are part of this short film. In a third instance, several years later, towards the end of 2018, the rise of violence in her community led Silvia to migrate to the United States seeking asylum.

This presentation is an exercise in self-representation and documentation. It weaves different periods and moments in Silvia’s life—very closely intertwined with that of her younger sister, Carolina, and the lives of their other siblings. They have had to separate various times because of migration (she has reunited with some of them in the United States). This story enables us to understand the forms migrant children create and recreate in the (trans)national space. How they connect, through their mobility, discontinuous territories like their indigenous community, the day labor fields where they worked during their childhood, and the United States, where Silvia lives now seeking asylum, and where Carolina longs to go to reunite with her siblings. The narration has let us also interweave, from conversations at different times, the present, past, and future of the two girls—currently young women of 17 and 20 years of age.

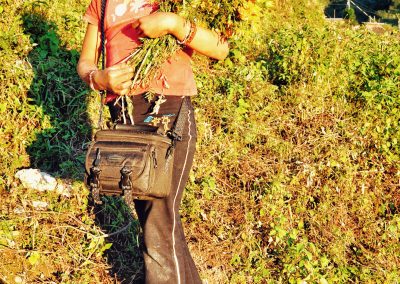

This story is unique and simultaneously very similar to the accounts of many indigenous and peasant girls in Latin America. Silvia and Carolina have had to face inequality, migrating far from their home community to work, with their family, in the farmers’ fields in the center and north of the country. For these two sisters, playing and working in the fields have been concurrent experiences, but now that both have stopped being girls, the struggle for economic livelihood continues. Silvia works exhausting shifts of more than ten hours as part of the cleaning crew in a company. At the same time, Carolina overcomes precariousness in her community. She dreams of returning to the United States—the country where she was born and had to leave as a baby—, to offer her son a “better life.”

Silvia’s story is that of a border that marks the difference between a life of permanent struggle against financial precariousness and the possibility of living far from violence and threats. A better life where getting a job provides her with enough income to build the future she wishes for herself, her sister, and her children. Hers is a story of how the border has divided the life of a family. Of how the experience has deepened the ties of blood and affection between two sisters that accompany each other from a distance.

Epifanio

In 2005 I met Epifanio, a Na Savi (Mixteco) indigenous boy who had migrated with his family from the Montaña de Guerrero region to Oacalco, Morelos, in search of work in the fields as a day laborer.

BY THE NUMBERS: CHILD-DAY LABORERS

Million Child Laborers

Million Children Work in Non-Permissible Activities

%

Million Work in the Agricultural and Livestock Sector

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT

It is estimated that in Mexico, there are about six million people living in day-labor homes. That is to say, to subsist, they depend on seasonal migration and work as day laborers (temporary and paid by the piece) in farmers’ fields. Most come from the states of Oaxaca, Guerrero, and Chiapas, where the internal migration flows are primarily made up of indigenous people and peasants. They are people pushed from their home territories by inequality, economic injustice, and failed public policies.

Although the day-labor farm work is considered a hazardous activity by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and other international organizations, in Mexico, thousands of children and adolescents keep doing it to survive. According to 2013 government statistics, in Mexico, there are about 1.7 million persons between the ages of 3 and 15 that make up day-laborer households; and at least 711,688 of them have as a their primary activity a remunerated job in these farms, which constitutes a severe human rights violation.

SOURCE: Red Nacional de Jornaleros y Jornaleras Agrícolas (2019) Violación de Derechos de las Jornaleras y Jornaleros Agrícolas en México. Primer Informe. Mexico City: RNJJA.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT SITUATION?

According to data from the Child Labor Module of Mexico’s National Survey of Occupation and Employment, in 2017 3.2 million children carried out some type of child labor, which is equivalent to 11% of the national children population. Of these, 2.1 million children worked in a forbidden occupation. 34.5% of them worked in the agricultural sector, which accumulates the highest percentage of child labor in Mexico, and is considered a hazardous occupation by the ILO.

How to Get Involved

It is crucial to demand that national and foreign farm businesses working in Mexico only produce products free of child labor. This demand should call for the removal of children and adolescents from production lines, and the guarantee of their right to education, food, housing, health, and healthy entertainment, as members of a day-labor household. At the same time, their parents may continue to produce the food we all consume.

It is fundamental to demand from local and national representatives from the leading agricultural states (Veracruz, Michoacán, Puebla, Jalisco, Estado de Mexico, Sinaloa, Guanajuato, and Sonora) that they enact better laws and public policies to protect farmworker families from labor exploitation. The DIF System, as well as state and municipal children and adolescent protection agencies, must do a better job protecting children and adolescents, so that families are not forced to find employment for their children in order to